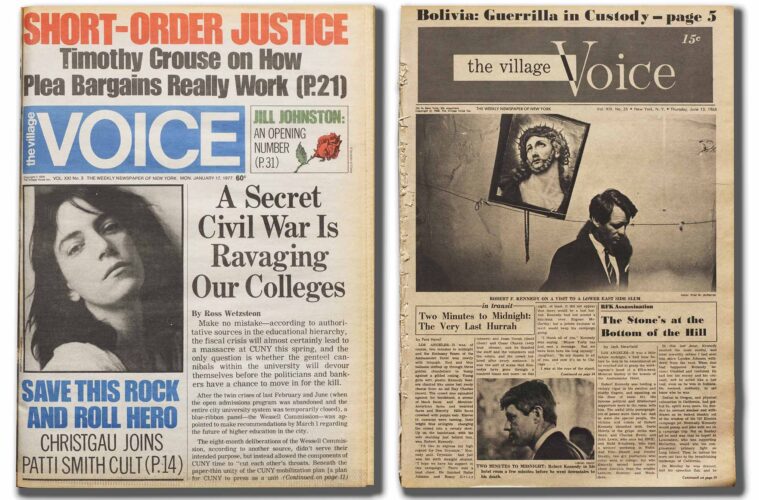

Imagine: Your Facebook feed is suddenly free of ads, and every post in it comes from one of your favorite Village Voice writers, cartoonists, or photographers. Staffers and freelancers at the legendary alternative weekly, alive and gone, are talking to you in the privacy of your room or on the bus or at the beach, their pithy comments bouncing off one another, sharing their memories and their inside scoops, assembling a saga that reaches back to 1955, when a trio of World War II vets — psychologist Ed Fancher, encyclopedia scribe Dan Wolf, and novelist Norman Mailer — threw 15 grand together, rented an office, and made publishing history.

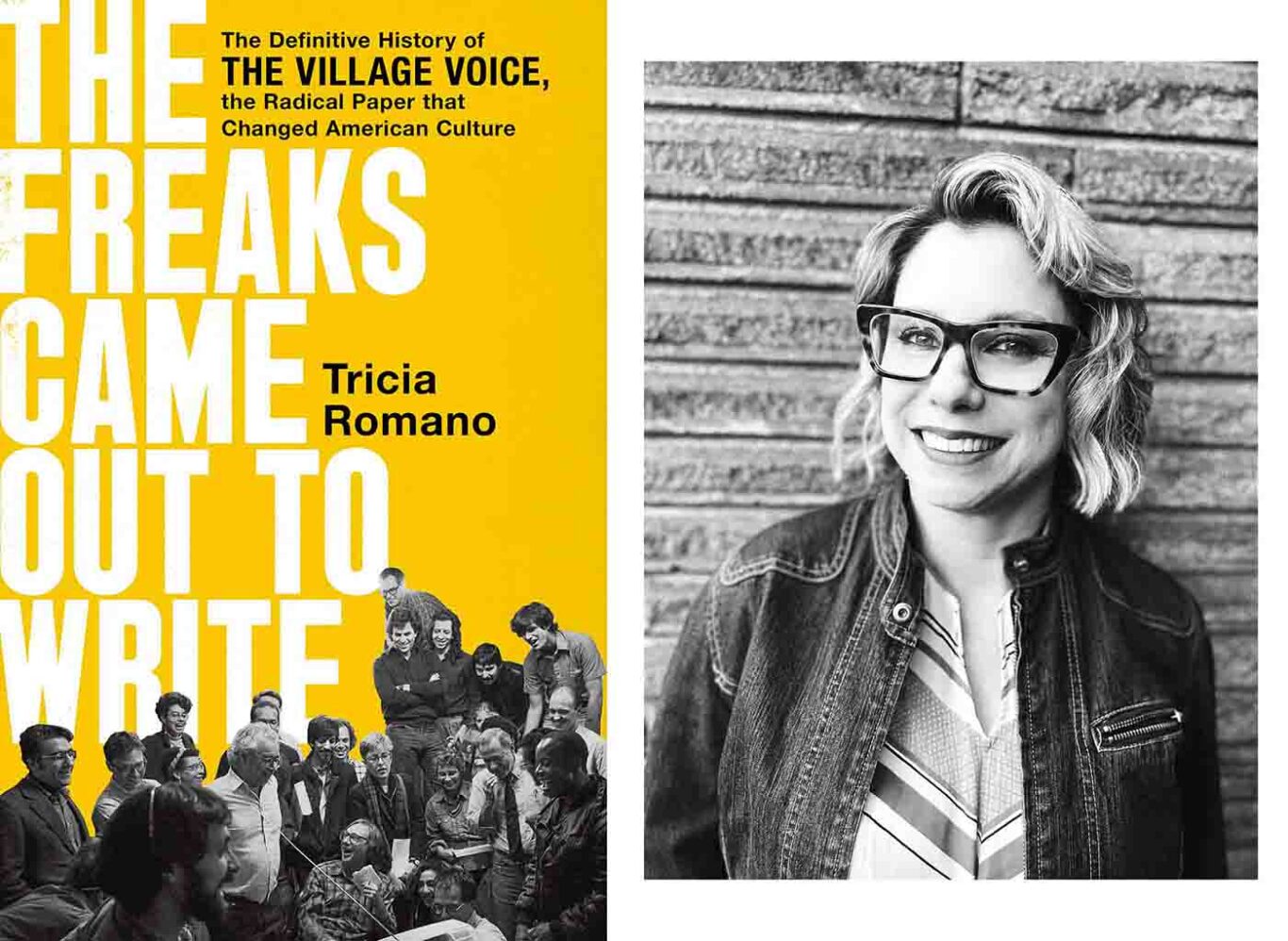

And imagine that this feed goes on for a hundred hours, that you keep scrolling and the stories keep rolling out, in the inimitable voices of people you knew — or wished you knew — and loved. That’s how I — a Voice contributor since the early ’80s, a senior editor from 1992 until 2006, and a contributor, again, from 2015 until, well, now — felt reading Tricia Romano’s extraordinary new oral history, The Freaks Came Out to Write, subtitled The Definitive History of the Village Voice, the Radical Paper That Changed American Culture.

Over the past half-decade, Romano, a nightlife columnist who worked at the Voice for eight years beginning in 1997, collated more than 200 interviews and researched dozens of books, articles, and audio clips by and about the unruly crew that came together in downtown Manhattan, their lust for truth and irreverent attitudes toward traditional media let loose by alert and sensitive editors.

The result is a triumph of contemporary journalism, a fusion of aesthetic and political positions, a chorus of sound bites from both union and management, unfurling a tale of wild success followed by a slow disintegration. Interspersed are brief quotes from stories that ran in the paper, letters to the editor, and observations from publishers, writers, editors, and IT and production staffers, revealing the thinking behind momentous decisions. Readers will discover the late Wayne Barrett’s prescient exposure of the habits of one Donald J. Trump, who first tried to buy off the dogged reporter with promises of a great apartment and then defamed him, having him arrested and jailed for crashing Trump’s Atlantic City birthday celebration. “I’m not there five minutes,” says Barrett, “and they slap the handcuffs on me. Defiant trespass, I was charged with … That’s a good representation of how Donald felt about me. All the cops down there moonlit for him.”

Lucian K. Truscott IV, grandson of a general who was Fancher’s commanding officer in Italy during World War II, sent letters to the editor, from West Point, where he was a cadet. One of them wound up on the Voice’s front page. Before he became a staff writer, Truscott would hang out with his colleagues in the editor’s office on Friday afternoons, drinking Wolf’s scotch out of little paper cups and then heading to the theater. “I remember thinking to myself, ‘Man, look at the lives that they lead.’ Christ almighty. It was just heaven on earth.”

The Voice’s offices were down the block from the Stonewall Inn, where a capricious bust in the summer of 1969 set off riots that mobilized the country’s gay rights movement. Says theater director Michael Smith, sometime writer and a producer of the Voice’s off-Broadway Obie Awards, “That whole scene happened right in front of my eyes.” Writer Susan Brownmiller comments, “It was the first time that the gays had resisted.”

Romano’s book leans heavily on the paper’s cadre of white guys, but a fierce phalanx of female writers and editors also have their say. Vivian Gornick, a self-described radical feminist, “saw sexism everywhere,” and would “write a piece that would point out the sexism of the situation.” The Voice, she recalls, “was a great proponent of personal journalism … It taught some of us how to do that kind of work well … They gave us the most astonishing amount of space and time, and it was amazing. You would think that they were the internet.”

I was fascinated to learn that while we in the trenches toiled to discover and document new developments in the arts and chicanery in politics, the folks holding the purse strings were struggling and scheming, finding ways to keep the whole enterprise on its feet through many changes of ownership. Goaded by a downtown rival, the New York Press, Leonard Stern suggested taking the paper free in 1996, to almost universal dismay. But his business acumen was sound: “We took our circulation from … 75,000 a week to 250,000, in stages,” Stern says. “It was enormously successful.” Immediately, ads and a T-shirt surfaced, with the slogan “The Paper That Can’t Be Bought.” (On my shelf sits a negotiation-month shirt reading “The Union That Can’t Be Bought.”)

I’ll never forget the afternoon staff meeting when managing editor Doug Simmons announced that on Wednesday mornings, when the free Voice hit the streets, it was outdrawing The New York Times. And of course, ad rates are based on circulation numbers. But a larger threat lay ahead: the emerging Internet and services like Craigslist, which undercut the paper’s classified section and caused it to begin hemorrhaging money. Romano unfolds all of this with almost cinematic power, as though she’d been a fly on the wall in the chambers where decisions were made. Listen to Anil Dash, an IT specialist, who came to the paper as a computer programmer in 2001: “My third day there, Craigslist launched in New York. I knew. I was like, ‘Oh my god.’” Dash got fired barely two years later, and wound up building tools for bloggers. “It was like we were the arms dealers to the rise of social media.”

There’s precious little narrative. The book is mostly constructed of first-person commentary, with a few editorial interpolations and a bunch of asterisked footnotes designed to explicate, for younger generations of readers, obscure references or errors of fact in some original quotes. Romano reveals where the bodies were buried, and where the seeds were planted. For pages on end, through the book’s 88 chapters, I found myself holding my breath, eager to see who, or what, she’d uncover next.

Mary Perot Nichols (1926–1996), an editor in the early days, helped to get John Lindsay elected mayor; later, he made her an assistant parks commissioner. “She got into a storage area under Central Park itself,” reports Clark Whelton, who wrote for the paper in the ’70s. “She was very curious, very nosy person, great newswoman … she started opening filing cabinets, and lo and behold, they’re the files of Robert Moses — all the goods on Moses, all his correspondence — because he had been parks commissioner at one time. She dials the phone and said, ‘Bob Caro, have I got a surprise for you. Meet me in Central Park.’” After two years, Nichols returned to the paper, becoming city editor. Her daughter, Eliza Nichols, tells Romano that Mary was very proud of the journalists she hired: “She was training people to do the work. Most of these people were very young and had not been journalists before.”

Nichols mère also threw parties where artists, politicians, and community planners mingled. “There was one night,” says Eliza, “when James Baldwin and Frank Serpico were there at the same time.” Declares ’70s Voice staff writer Howard Blum about these parties, “You were able to develop sources. You could be a kid of twenty and have better sources and know [more] people on a social level than people at the Times who were reporters. It was very handy to me when I went to the TImes.”

Romano devotes chapters to the designers and photographers who gave the paper its unique look, and to the succession of figures who bought the company and tried to corral the obstreperous crew who wrote and edited the paper. Lavish space is given to the writers of color, such as Stanley Crouch, Greg Tate, Hilton Als, Peter Noel, and Lisa Kennedy, who made inroads at the Voice when other publications had little space for them and their cultural touchstones, like hip-hop. Gay culture had such a firm foothold that some people referred to the Voice as a gay paper. Writers like Jeff Weinstein (art editor, restaurant critic) and Lynn Yaeger (who spent years as a clerk in the classified department before landing her fashion column, and is now at Vogue) were essential to the groundbreaking union contracts that provided domestic-partner benefits for staffers, long before such matters were enshrined in law.

There is stuff missing, of course. Six hundred pages is fat for a mass-market book, and a lot of material was trimmed along the way, for size and probably for legal reasons. The dance section is absent, for one thing, except for a brief quote from Deborah Jowitt about her first forays into the paper, in 1967. Burt Supree, a poet, actor, and author of children’s books who got hired as listings editor because he was a very fast typist, became a dance critic; he edited Jowitt (and later, me) from 1976 until his sudden death, in 1992, and he too goes unmentioned.

A lot of us are lifers, as readers, contributors, editors, and now, in the scaled-down universe that is villagevoice.com, contributors again. People showed up straight from college, because working at the Voice had always been their dream, despite substandard wages and word rates, paltry expense budgets, and barely habitable offices. Art writer Vince Aletti, now a contributor to the New Yorker, who freelanced for the music section under Robert Christgau, the “dean of rock critics,“ says, “We weren’t making much money, but we all were dying to talk about the things that we were excited about.” Editors like Christgau and the late Robert Massa nursed young writers, turning promising aspirants into excellent stylists who midwived a generation of change. Says Christgau, “I gave Gary Giddens his column and encouraged him to write longer and more ambitiously. I could see he was a fucking genius. The music section was suddenly in flower, and people were flocking to it. I remained on the lookout for new writers all the time. I can’t tell you how exciting that was.”

(PUBLICAFFAIRS/HACHETTE; PHOTO OF ROMANO BY MORGAN BELL)

People left for greener pastures … and then came back. Playwright Brian Parks, a copy editor, went to New York magazine but returned and wound up running the theater and dance sections. Tom Robbins, political writer and union stalwart, left the Daily News to return to the Voice under editor Don Forst; Joe Levy, sly music writer, briefly inhabited the editor’s chair a decade later. Others now fill prestigious posts across the country (Charles McNulty at the Los Angeles Times; Guy Trebay, Manohla Dargis, and Alexis Soloski at The New York Times; Hilton Als at the New Yorker). Voice writers have earned the paper three Pulitzer Prizes and countless other awards. Colson Whitehead, who started out writing wittily barbed reviews of television shows for the Voice, has since pulled down a Pulitzer and other honors for his novels.

The Voice’s sports section, The Score, established in 1981, came and went over the decades. It had a deep bench of good writers, including Ishmael Reed, who wrote about boxing. “Nobody even knew the Voice had a sports section,” reports Michael Caruso, who edited it in the ’80s and is now publisher of The New Republic. “Nobody knew why the Voice had a sports section, and as a result I could do anything I wanted…. We were such a weird animal. We weren’t apples or oranges. We were like a kumquat.” Editor-in-chief Karen Durbin killed it in 1995, but the section was restored a few years later. One editor, Jeff Z. Klein, who wound up a hockey reporter at the Times, says, “A couple guys there said to me, ‘Oh, the Voice sports section? I love it.’ They’d pull out of their drawers little things we’d written.” (Let it be noted that the paper so ambivalent about sports is commemorated, on the cover of Romano’s tome, by Catherine McGann’s photo of 21 staffers in the office huddled around an old portable TV, watching the Mets play the Astros in Game 6 of the National League Championship series, in 1986.)

The paper flourished in what was clearly a different time — before the Internet, before Craigslist, even before word processors. It started out as a very local weekly, became a national phenomenon, and suddenly found itself, by virtue of going online, an international daily. It abides, stewarded by editor R.C. Baker — artist, art writer, and longtime print supervisor at the paper, who tells this story of the evening of 9/11: “Don [Forst] came up with a very Daily News/New York Newsday headline: ‘THE BASTARDS!’ … I’m waiting for the LIRR. On the other side trains were pulling in, and people were pouring off the trains. On my side, there was me and two other people because no one was going into the city. I’ve got thirty copies of the issue in my messenger bag, and this guy comes up to me and just doesn’t say hello or anything. He says, ‘Did you see what those bastards did?!’ … I couldn’t help but laugh. I said to him, ‘Mister, you need this.’ I handed him a copy. And there it is, ‘THE BASTARDS!’ across the cover of the Village Voice. So, Don’s instincts may have been right.”

The arc of the Village Voice has been long, but it’s bending toward … not quite mass extinction but, along with every other media outlet except maybe the Times, becoming a shadow of its former self. The Freaks Came Out to Write begins as history and ends up, 525 pages later, as testimony to the work the paper used to do, work that is barely possible any longer for professional journalists to do. The Voice welcomed contributors because of the quality of their writing and didn’t bother checking for degrees in journalism, or degrees at all: Neither the late Peter Schjeldahl nor Deborah Jowitt, legendary art and dance critics, respectively, graduated from college. (The current Voice website continues this tradition, but with the diminished resources typical of our post-Craigslist mediascape.)

Romano was still in college when the Internet began upending journalism, torpedoing our attention spans and making it redundant to cart around sheaves of newsprint. She’s processed 70-odd years of publishing history into bite-size bits, and created an irresistible party platter of a book, rich and essential. ❖

Elizabeth Zimmer has written about dance, theater, and books for the Village Voice and other publications since 1983. She runs writing workshops for students and professionals across the country, has studied many forms of dance, and has taught in the Hollins University MFA dance program.

Editor’s note: The disclaimer below refers to advertising posts and does not apply to this or any other editorial stories. LA Weekly editorial does not and will not sell content.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.