When Chuck Dederich opened Synanon in a storefront on the Venice Boardwalk in 1958, it was the only residential drug rehab that existed in Los Angeles. There were no doctors or nurses or methadone for the heroin addicts. It was just addicts helping addicts with puke buckets and cold towels to help the dope sick come down.

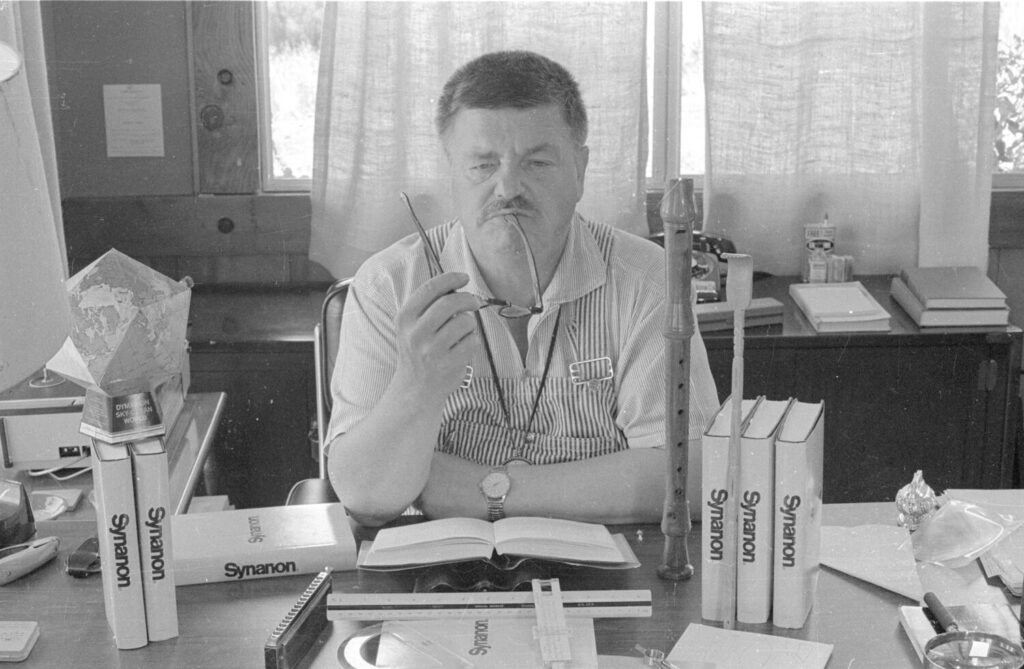

Dederich was a middle-aged alcoholic who cleaned up in Alcoholics Anonymous in 1956 and a former PR man. Right out of the gate, he became an immediate media sensation with the success of Synanon saving lives and the introduction of confronting therapy into the program, popular at the time.

He called it The Game. It consisted of group sessions between addicts discussing their problems three to four times a week with members telling each other what assholes they all were in a supervised verbal street fight. It was an emotional catharsis for people who had spent their lives pushing down their demons and feelings with drugs and alcohol. And it worked.

Prolific award-winning documentary producer Rory Kennedy and partner Mark Bailey’s upcoming HBO series The Synanon Fix takes a fascinating plunge into the rise and fall of the Synanon organization through the eyes of the members who lived it from its early days as a groundbreaking drug rehabilitation program to its later descent into what many consider a cult. What began as a story of healing ended in horror.

Chuck Dederich (Bruce Levine)

The husband and wife team collected more than 35,000 photos and more than 3,000 pieces of archive video from different places and sources and interviewed a wealth of Synanon survivors, including Dederich’s daughter Jady and others born into Dederich’s movement, and Lance Kenton (the son of famous bandleader Stan Kenton) who went to jail for allegedly placing a live rattlesnake in the mailbox of attorney Paul Morantz in 1978 by orders of the charismatic leader, to silence his investigation into Synanon practices.

“I’ve been making documentaries now for 30 years and I would say on average most of my interviews are about two hours,” Kennedy told L.A. Weekly recently. “I did a longer one for the Vietnam documentary that was about four hours. A biopic like I did with my mother was over a few days. None of these interviews were less than seven hours. Many of them were nine hours or longer and I never got bored. They’re great talkers and all know how to tell a story. The changes that went on in their lives were fascinating. To see how they made sense of this organization that went from the pillars of Synanon in the beginning when the only rules were no drugs, no alcohol and no violence. By the end they had bought more firearms than anybody in the history of California and had an open bar. I mean how do you go from A to Z like that? When you’re inside of that bubble, how do you make sense of that?”

The series, which premieres on HBO on Monday, April 1, makes sense of it by approaching the story with an understanding of the context of the times. It gets down and dirty and is unflinchingly honest about everything from child abuse to birth control mandated by Dederich, including vasectomies for men as part of its lifetime rehabilitation. Children were subjected to the same Game sessions as adults in chilling original footage.

“There was a lot of damage done,” says Bailey. “Some of the children who either came in young or were born into and grew up in Synanon ended up as collateral damage while the adults were on their journeys of discovery. But parenting in general at the time was different than it is now. You have to see it through the lens of the time and what they thought that relationship should look like.”

Inside Synanon at the Casa del Mar (Courtesy HBO)

By 1961, they outgrew the Venice storefront and expanded, moving to a vacated armory on the beach in Santa Monica, where about 60 people were fed and housed. It was free to those in need. The recovering alcoholic started running it like a corporation and Synanon became a nonprofit organization, becoming inundated with donations.

He was the edgy darling of the time with international coverage, and in 1968, his social movement continued to grow and made what is now the ritzy and restored Casa del Mar hotel in Santa Monica the group’s headquarters until 1985.

Amid the growing cultural revolution, Dederich and his wife, Betty, opened Synanon’s doors to nonaddicts, known as “lifestylers,” and turned the organization into a culturally forward attempt at communal living. Membership swelled to the thousands and Synanon’s facilities grew in number around the country.

“I have fantastic memories of growing up in Synanon,” says world-renowned choreographer Bill Goodson, who grew up in the group and went on to work with Michael Jackson, Diana Ross, Paula Abdul, Stevie Wonder and Gloria Estefan. “It saved my mother’s life and it probably saved mine as well. I can’t think of a better place to have grown up in, living in a community with other kids who became my brothers and sisters of every different race and color. It wasn’t perfect and there were some dark moments as well, but my memories on the whole are very fond.”

“I think it changed when the kids started playing The Game,” says Goodson, who with his mother, an admitted “dope fiend” appears extensively in the series. “Up until then, we were a community of children who grew up like most children, we went to school together and played outside. There was always a mother if not mothers in the house where we lived, so we were fed and looked after and spent a lot of time going down to the Del Mar club, immersed in a place that was helping people. Some people came in needing help who were sick and, yes, sometimes you’d find yourself emptying a puke bucket or giving somebody a cold towel who was on the couch. That was part of our lives. Other than that, we had pretty great childhoods growing up on the beach.

Synanon women shave their head as part of a liberation, February 27, 1975 Photo ran 2/28/1975, p. 1 (Photo by Vince Maggiora/San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images)

“Synanon didn’t know anything about raising kids, so they began to implement these therapeutic methods that they used on adults and dope fiends on us,” he says, holding back tears. “Looking back, it was a dreadful mistake. Kids who were strong enough and able to roll with the punches and bounce back survived these difficult moments. Then others didn’t and couldn’t. My heart always goes out to them.”

Goodson left the group in 1976 and says he never underwent therapy or deprogramming.

“I found myself suddenly in a dance and arts community that was thriving and alive,” he says. “It was California in the ‘70s. There were a lot of people embracing new ideas and I fell into a situation that wrapped its arms around me. In many ways, it felt like Synanon. I didn’t feel a void. At 19 and recently divorced with the work ethic I learned already in jobs at 16, I had a step up on my peers. I started a dance career pretty late in life and was dancing with Diana Ross in no time. I attribute that to my upbringing. I tried to take the best with me when I left.”

The Synanon Fix is a comprehensive first-hand look at the social movements of Los Angeles in the ‘60s, integration, cults, communes and greed.

“I was reading about cults recently and that there are about 10,000 cults in the U.S. today, depending on how you define it, which was way more than I expected,” says Robert F. Kennedy’s daughter, Rory, who was born six months after her father’s assassination. “It said that during times of chaos or where society itself feels out of control — which was true in the early ‘60s in the streets of America and Vietnam — it feels very unsettling. In times like that, much like now, people are searching for ways to be grounded or for a new way to help them make sense of the world in friendships, relationships and community. The feeling of community seems more crucial when the world around us is so chaotic.”

Rory Kennedy ( Rainer Hosch)

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.