Up to 150,000 deceased Americans go unclaimed each year, about 2,000 of them in Los Angeles. In Pamela Prickett’s and Stefan Timmermans’ new book, THE UNCLAIMED, the authors take a detailed and revelatory look at the difficult truth that anyone, even the wealthy and famous, can be abandoned when they die.

The book is eight years in the making and follows four Angelenos from 2012 to 2019 who fell through the cracks of estranged families and the complicated and bureaucratic system of dying in L.A. County. Side by side with medical examiners and death scene investigators, the authors document the compassion, care and dignity given at the moment of discovery that sort of takes away some of the shock value of discovering a recluse in a neglected dwelling after decomposition had set in and a neighbor reported a foul smell.

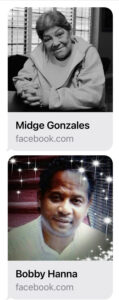

Through extensive research and feet on the ground, Prickett and Timmermans document how these four souls’ remains went unclaimed at the end of life — Bobby Ray Hanna, a once-homeless Air Force veteran who lived at the Veteran Administration’s Westwood campus and performed with the New Directions Veterans Choir on America’s Got Talent; Lena Brown, an 89-year-old Jehovah’s Witness who owned a duplex in Hawthorne; David Grafton Spencer, a Scientologist who told tall tales; and Nez “Midge” Gonzales, who became embedded in the Westchester Church of the Nazarene community after living on the property in her van.

They did numerous observations of the death investigations alongside Kristina McGuire from the coroner’s office. They sat next to Joyce Kato in the medical examiner’s office when she contacted the decedent’s relatives. They attended funerals in San Diego for abandoned babies in the Garden of Innocence and have been going to the L.A. County Boyle Heights potter’s field ceremonies for the last five or six years. That burial ground is located next to L.A.’s oldest cemeteries, Evergreen, and the L.A. County Crematorium. They also attended many of the vet ceremonies in Riverside.

“The Boyle Heights ceremony is the easier one to talk about,” Timmermans, who is a professor of sociology at UCLA, tells L.A. Weekly. “You know L.A. It’s a city of loneliness and isolation. It’s a city of cars. Here we come together on a December morning, all strangers to one another. About 200 people are standing around a gravesite of 1,500 to 2,000 Angelenos whose relatives were unable or unwilling to bury them. You get this sense of connection to these strangers around you, a unique moment of belonging and community. These people have been abandoned, but here we are as their surrogate family. You don’t necessarily talk to each other, but there’s music and prayers in a multi-religious send-off to these unclaimed dead. Janice Hahn is there, representatives from various religions and a lot of strangers. It’s very powerful. It feels like you’re there to do something completely selfless, honoring these people who had nobody else to mourn them. You feel a connection in this huge isolated city.”

Not forgotten: Longtime L.A. Country Crematorium worker Craig Garnette prepping the grave for the 2015 ceremony (Courtesy Stefan Timmermans)

Timmermans says there are a million reasons why families become estranged and illustrate how those relationships become fractured in the histories of Hanna, Brown, Spencer and Gonzales.

“There are a lot of people who die homeless or come out of fractured families who do get claimed,” Timmermans says. “But the fracturing of the family and estrangements is definitely being revealed to the rising numbers of unclaimed bodies. The argument we make is that going unclaimed used to be reserved for the most indigent of the indigent. Even migrants coming to a new country would pay into funeral funds to avoid going to a pauper’s grave. Everyone tried to avoid that fate as much as possible. What we see now are different groups of people becoming at risk of going unclaimed, and the risk factor that explains it is that they often have estrangement in their family.”

According to U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, the unclaimed reflect social isolation caused by eroding family ties. Their deaths are the endpoint of what he calls “our epidemic of loneliness and isolation.” It boils down to one key question: will you have someone to claim you? When we don’t, we’re at the mercy of our local overstretched governments to organize a burial or cremation. American households have changed in recent decades. More of us are living alone, more of us are divorced or never married, more of us are childless, and more of us — nearly one in four — are estranged from close kin. We can no longer assume there’s someone to care for our bodies when we die.

Unclaimed marker for 2014 (Courtesy Stefan Timmermans)

“It’s societal,” says the professor, whose purpose of the book is to put this phenomenon on the map. “The polarization around politics, religion and sexuality is driving families apart. Most deaths are unexpected and a funeral is an unexpected expense. Are you going to do that for Uncle Joe who you haven’t seen in decades? Or the father that walked out on you? Or the aunt you’ve written off in the nursing home you haven’t visited in six years? We would have said yes for a long time and now we are seeing a change.”

The most gut-wrenching of all is the rise in abandoned babies. At the Garden of Innocence in San Diego, ritualized ceremonies are held annually where volunteers and family surrogates come together to remember the unclaimed. And not just any baby, but a baby that has been abandoned.

“It provokes profound questions,” says Timmermans. “Somebody abandoned this baby, what’s the meaning of their life? They pass the casket around at the beginning and welcome the baby into the community and then at the end, they release doves into the sky to send the baby away. You’re taken on a journey in this ceremony where you feel the grief and then let it go. Quite a few people there have unresolved issues in terms of stillbirths or lost their own children and have not completely come to terms with that. This ceremony allows them to channel some of that grief. It’s an extraordinarily supportive and welcoming community. If you’re alone and you’re grieving, it’s a double burden, but if you can share it; you’re not carrying that burden by yourself. That little casket that gets passed around and you can feel how light it is. Some people go and never go back because it’s just too difficult.”

Few people are aware of how many people go unclaimed and that the numbers are increasing and more different people are at risk. Wealthy people have family estrangements and get left to the county for burial.

“We want to start a conversation where people reflect on where they are,” he says. “Who is going to be there for you when the time comes to claim you? It’s a very sensitive barometer of family relationships. If you don’t feel that there’s an answer to this and a person doesn’t immediately jump into your mind who you can count on — maybe that’s a wakeup call to maintain or repair relationships.”

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.