A 1961 photo essay that sparked controversy gets a new life — and a Getty Center exhibition

In 1961, celebrated photographer Gordon Parks was assigned by Life magazine to create a photo essay on poverty in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. Originally he was to follow the daily struggles of a working class family man, but instead Parks chose an undernourished boy named Flávio da Silva, caregiver to his six younger siblings. The blockbuster story that came of it sparked a saga interwoven with themes of fake news, Cold War politics, and imperialism — but it mainly seems to be their friendship on display at the heart of Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story, at the Getty Center through November 10.

Parks, who spent 11 years on the Life magazine masthead, had resigned only a year before the assignment when he agreed to photograph its subject, which was well within his wheelhouse, judging by previous assignments documenting Chicago’s Southside in 1941, or in 1942 the life of Ella Watson, a custodian at the FSA (Farm Security Administration) in D.C. where he worked at the time.

For context, in January of 1961, President Kennedy had announced the Alliance for Progress, an aid program meant to counter Fidel Castro’s influence in Latin American countries. Parks’ photos would constitute the second installment of Life‘s corresponding series titled Crisis in Latin America, under a headline reading, “Freedom’s Fearful Foe: Poverty.”

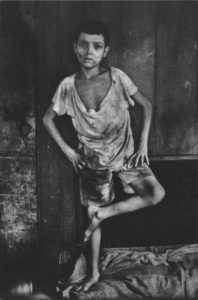

Gordon Parks, Flávio da Silva, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1961 Gelatin silver print. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council © The Gordon Parks Foundation

A day after his arrival in Rio, Parks spotted Flávio at the foot of a steep path in the Catacumba favela and decided on his subject. “This one resonated in part because of the age of Flávio, he was only 12,” says Getty associate curator Amanda Maddox, who collaborated on the show with Paul Roth, director of the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto. Maddox adds, “Flávio was on the verge of death, he was severely asthmatic. That made it one of the most heart-wrenching stories that Parks ever covered.”

The story ran across a mere 12 pages in Life’s June 1961 issue, with images of Flávio messily feeding his baby sister, pouring boiling water as he prepared breakfast for his younger siblings, and the family of nine crowded into two squalid be

ds. The response was immediate — $30,000 in unsolicited donations heading for the aid program.

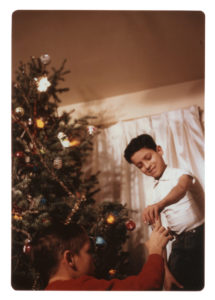

A month later, on July 5, Flávio flew to the U.S. to receive treatment for his asthma at Denver’s Children’s Asthma Research Institute and Hospital, where he was restored to good health. His two years in Denver are glimpsed in candid photos by José Gonçalves, whose family hosted Flávio in their conventional, comfortable suburban lifestyle of school, sports and social events with kids own his age.

“The Gonçalves family were very responsible and helped me get to school and learn English and writing and there was no difficulty. I learned in one month. I was a child, and children learn faster,” says Flávio. Now 70, his recent arrival in L.A. marked his first visit to the U.S. in 58 years — to the day.

José Gonçalves, Untitled (Snapshot of Flávio da Silva and the Gonçalves Family), Negative 1961-63; printed 1976, Chromogenic print. (The Gordon Parks Foundation)

While young Flávio was in Denver, his family in Rio was relocated from their shack to a simple concrete home in a working class section of the city, outfitted with conveniences like running water and a washing machine. All were happy about the change in circumstances; all except the politically vulnerable Brazilian President Janio Quadros, who was not pleased with the unflattering depiction of his nation’s most famous city.

Photographer Henri Ballot was soon dispatched by one of Brazil’s most popular magazines, O Cruzeiro, to New York City where his assignment was to return with similar photos depicting unspeakable poverty. In the magazine’s October issue, his images were juxtaposed with those by Parks. The dispute escalated when each accused the other of staging photos — hence the charges of “fakery.” To Parks, the conflict only drew attention away from the horrid conditions he’d sought to illuminate.

“There were accusations about the situation but it was not true,” says Flávio. “There’s nothing that was made up. It’s important everyone know that,” he says, emphasizing the persistent crippling poverty in the favelas. “Even today, from 1961 to 2019, it’s still the same. It doesn’t change.”

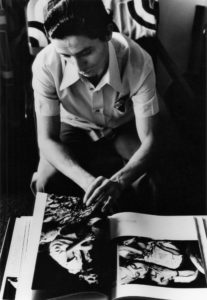

Gordon Parks, Flávio da Silva Looking at Gordon Parks’s Book Moments Without Proper Names, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1976, Gelatin silver print. The Gordon Parks Foundation © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Parks and Flávio kept in touch through the years, meeting again in the 1970s when Parks published a book, Flávio, on their experience together. By then, the photographer had found success in Hollywood directing the hit film, Shaft. Flávio went on to marry and have children, then separate from his wife. He worked cleaning and construction jobs, a long stint as a security guard, and in a restaurant for a spell. Parks and Flávio were united again in the 1990s, when the former was in Brazil shooting a documentary. It was the last time they met before Parks’ death in 2006.

During that visit, Flávio asked about people he knew during his childhood visit to the U.S., and learned that many were dead. “That broke my heart because some were friendly and lovely people to me,” he says. “I had been accepted with love and good treatment from everyone.”

Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story is on view at the Getty Center through November 10.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.