This story was originally posted in our sister paper, the Village Voice.

Muddy Waters Restored in Rolling Fork: The March tornado that destroyed the Mississippi hamlet near the birthplace of blues icon Muddy Waters hurled debris some 200 miles northeast to the town where Elvis was born.

“Somebody found the will of the husband of a friend of mine in Tupelo,” said Leslie Miller, president of the Rolling Fork Visitors Center and Museum, also destroyed.

Miller was giving a tour this past November of the extensive damage remaining eight months after the storm, which roared south to north some 60 miles from Rolling Fork to Silver City. The death toll has fluctuated between 15 and 17, with the population dropping from a reported 1,883 before the storm to fewer than 1,600, as many of the displaced have not returned. The storm uprooted trees over a hundred years old, tossed trucks and buses across fields, and caused an estimated $10 million in damage.

“It came through like a big machine, rumbling and shaking. I found my workshop across the street near a water tower that was knocked down,” Lee A. Washington, 70, a retired army sergeant and metal sculptor, tells the Voice. He used insurance money to repaint his corrugated steel art gallery (an early-20th-century petroleum depot) bright green. In general, he says, recovery in Rolling Fork “has been real slow.”

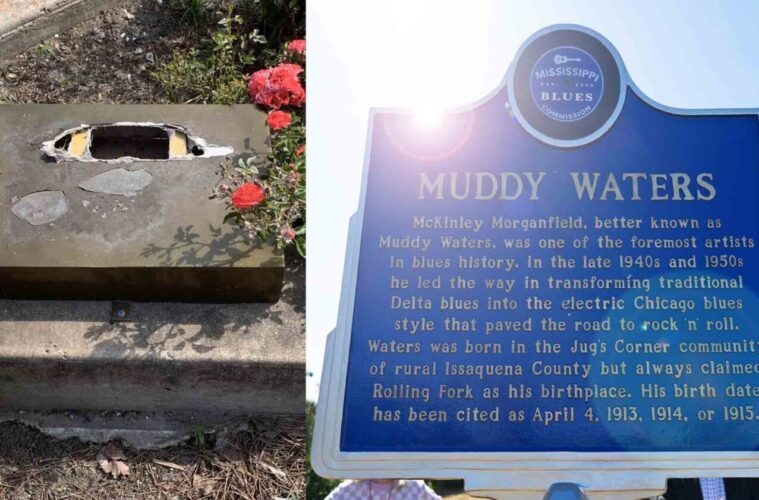

Back when his grandmother gave toddler McKinley Morganfield his legendary nickname after his fondness for playing in mud puddles, Rolling Fork was a stop on the Illinois Central rail, which ran between growing blues mecca Chicago and jazz haven New Orleans. It was where country folks outside of town went shopping and got their mail. Today, the post office has not yet reopened in its former building, nor has the police station, City Hall (now in a trailer), or the library, its books freeze-dried and stored in Yazoo City. The town’s main attraction — a 200-pound cast-aluminum Blues Trail marker honoring Muddy — was sheared from the ground and has not been found. One of more than 200 markers located throughout the Magnolia State, it was replaced on November 4, purchased with an emergency grant of $15,663 from the National Endowment for the Humanities to the Mississippi Humanities Council and unveiled at its original spot on Walnut Street.

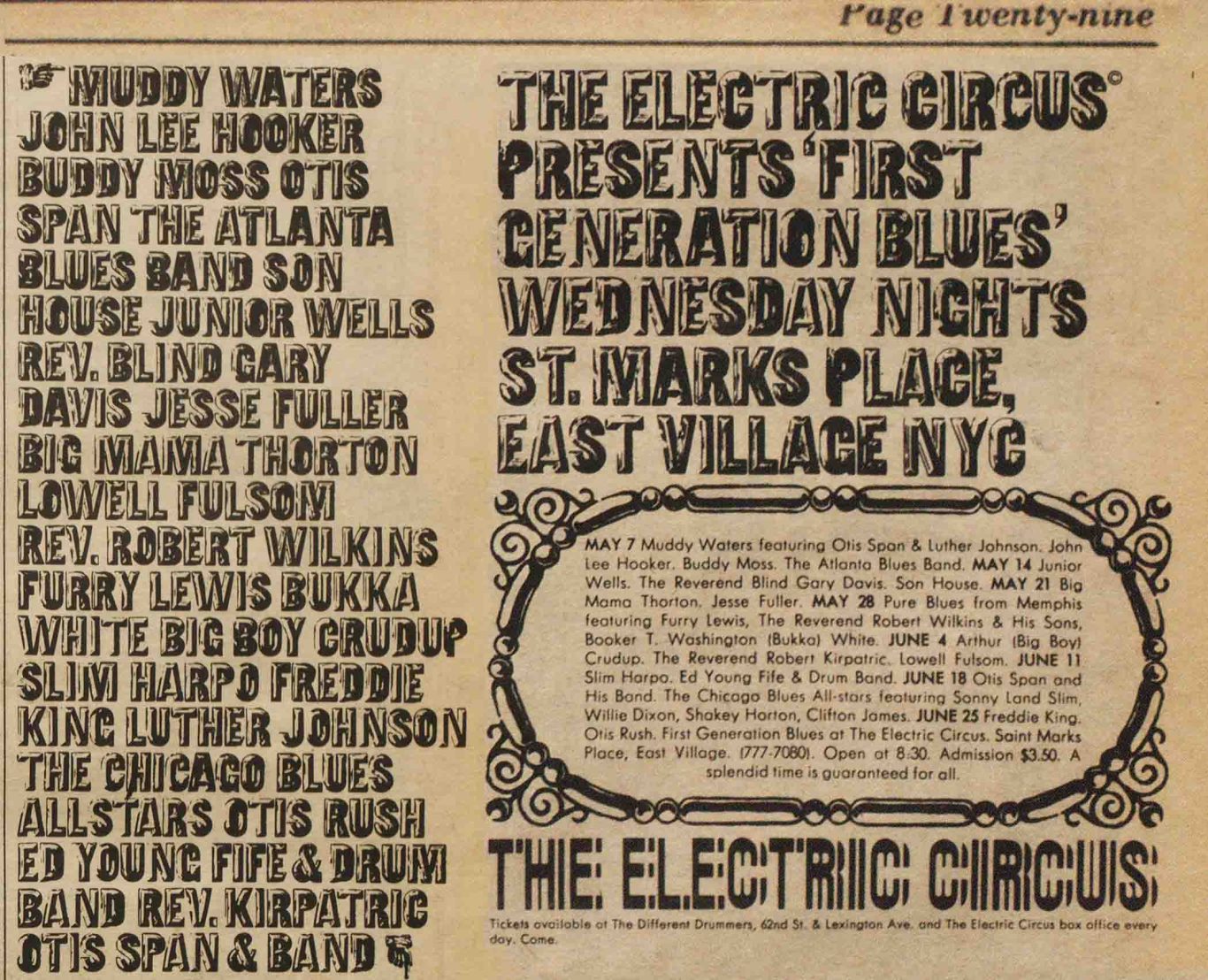

Muddy Waters gets top billing at a counterculture bastion, in an ad from the April 24, 1969, issue of the Voice. (VILLAGE VOICE ARCHIVE)

The NEH was represented at the ceremony by senior deputy chair Tony Mitchell, who — under bright blue skies — quoted the poem Planet, by Mississippi poet laureate Catherine Pierce: “This morning this planet glows with dustless perfect light …” While confessing to only a passing knowledge of the blues, Mitchell is a fan of Jimi Hendrix, the guitar god of the Woodstock generation who paid years of dues as a chitlin’ circuit sideman before erupting into rock stardom. In 1968, Hendrix told Rolling Stone, “The first guitarist I was aware of was Muddy Waters. I heard one of his records when I was a little boy and it scared me to death because I heard all of those sounds. Wow, what is that all about?”

Heonjin Ha traveled 11,000 miles, from Seoul, South Korea, to play those sounds at the dedication, putting everything he had into a rendition of Muddy’s Long Distance Call, a top ten R&B hit from 1951 on the Chess label. Performing in place of Kevin Johnson, Muddy’s great nephew, who had a conflicting gig, Heonjin put a glass slide on his pinky, closed his eyes, and wailed: “You said you love me baby / Please call me on the phone sometime … ”

The locals, immersed in the blues all their lives, were impressed. Afterward, over a brisket platter at Culley’s Bar-B-Que, in Vicksburg, Heonjin savored his meal and the honor. “Driving [north] from Jackson through national forests and cotton fields, I wasn’t sure what to expect in Rolling Fork. The tornado damage was worse than I imagined,” he recalls. “I still can’t believe I got to play there. I was nervous, but I wanted to play for Muddy.”

Born in Jug’s Corner on the outskirts of Rolling Fork sometime between 1913 and 1915, Muddy Waters is synonymous with the music he carried in 1943 from Stovall Plantation to the southside of Chicago, part of Black America’s Great Migration. His music — acoustic in the Delta, electric in the big city, and carried by his passionate voice — has been played the world over since the early 1950s. “Tourists from about 30 countries have visited Rolling Fork over the years [because of] the connection to Muddy Waters,” explains Miller, adding that she still wasn’t sure when the visitors center would be rebuilt.

The grant that replaced the Blues Trails marker will also fund replacement of two other historical markers, each connected to President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1902 visit to the Delta to hunt bear. His guide was legendary sportsman and bear hunter Holt Collier, born into slavery in 1848. Tales from the hunt, during which Roosevelt refused to shoot a large male bear that had been tracked to exhaustion by Collier and tied to a tree, led to a novelty popular since its debut: the Teddy Bear. But most visitors — many of them white baby boomers raised on the music of the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin — are interested in the blues, which, as Waters sang, “had a baby and they named it rock and roll.”

Willy Bearden, an independent filmmaker, grew up in Rolling Fork and lives just south of Memphis. With Hollywood producer and fellow Mississippian George Larrimore, Bearden is creating a three-part documentary on the Delta tornado for Mississippi Public Broadcasting. The first episode aired in mid-October; part two, scheduled to run in January, includes the story of the lost Muddy marker.

Seoul bluesman Heonjin Ha pays homage to the legend, performing at the dedication of the new Muddy Waters marker. (Rafael Alvarez)

“George called me when the tornado hit and said we gotta do something,” Bearden tells the Voice. “George is 75 and I’m 73. Time to get off the bench for one more caper. I can’t swing a hammer, but we can tell the story.”

The filmmakers use the Waters sign — first erected in 2007 — as emblematic of changes toward the blues in the land where it began. It wasn’t so long ago that blues culture and its attendant poverty were viewed by some in state authority as an embarrassment. “People visiting the Mississippi Delta and seeing it for what it is — the wellspring of American popular culture — is pretty recent,” says Bearden. “Twenty-five years ago people thought I was crazy for saying people would want to come down here. Now we have museums up and down Highway 61.”

The Delta Blues Museum, a hundred miles north of Rolling Fork, in Clarksdale, holds the remains of the cabin Muddy lived in on Stovall Plantation. Blues scholar Scott Barretta, who spoke eloquently of the music’s enduring power at the dedication, described how “people were stealing pieces of wood” from the cabin when it stood in the fields. It was on the porch of that cabin that Alan Lomax recorded Muddy for the Library of Congress in 1941 and 1942, released on Testament Records in 1966 as Down on Stovall’s Plantation.

Hearing his voice for the first time after Lomax sent him a copy, Muddy is said to have remarked, “Man, I’m good.”

Muddy Waters Restored in Rolling Fork: Rafael Alvarez has been writing about the Delta Blues since the 1980s, covering the funeral of Muddy Waters in 1983. He is currently at work on a biography of the New York City blues guitarist Robert Ross.

Editor’s note: The disclaimer below refers to advertising posts and does not apply to this or any other editorial stories. LA Weekly editorial does not and will not sell content.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.