(Mark “the Cobrasnake” Hunter)

Indie Sleaze Flashback: The Cobrasnake and Pre-Instagram Y2K Nightlife Revisited

It’s hard to imagine or barely even recall now, but once there was a world in which “selfies” did not exist. Print and TV media were the biggest “influencers” of culture. Typing messages on a phone or “texting” as it came to be called, was a weird and novel way to communicate. And a bold new social ecosystem was emerging on the internet, allowing us all to redefine ourselves by crafting something we never had before: an online persona. Friendster was first, providing a place on the web that showed us who we knew and who our pals knew, inspiring connections. But it was quickly crushed by MySpace, a sexier, savvier online meetup and “place to share friends” as the slogan touted, where we posted our interests and music lists, building a network of BFFs both real and faux (all starting off with the same nerdy guy, co-founder Tom Andersen).

Imagery was, of course, the most important part of this equation, but we didn’t always have pictures to choose from like we do now; definitely not digital ones. We didn’t document every move, meal, outfit, concert or sunset, mostly because there really wasn’t a convenient way to do so. If you wanted snapshots of a wild night out on the town, for example, you had to bring a camera or hope that the party or club had a photobooth, or more preferably, a real, roaming photographer who might post pics on the event’s website the next day. In the early aughts, Mark “The Cobrasnake” Hunter, a bespeckled, curly haired teenager from Beverly Hills and one-time assistant to artist Shepard Fairey, took the concept and made it his own, strapping on an SLR and diligently documenting the nightlife scene in L.A., just because he could.

(Mark “The Cobrasnake” Hunter)

Anybody could have and eventually many did try to do what he did, but nobody got what he got on film and nobody put it all out there in a blog in the same shameless, immediate and extensive way. Cobrasnake’s colorful workout-wear aesthetic garnered attention and his unassuming yet ironically hip aura attracted equally freaky and fabulous young adults who liked to go out – some famous, some infamous in the underground, most neither until he chose to feature them in a photo. Many were eager to mug in front of his lens like drunken supermodels at an effed-up fantasy fashion shoot, and when he saw certain scenesters had something special, he made them his muses.

But beyond the effortless appeal of anti-model Cory Kennedy and her messy-tressed ilk, his focus was on redefining fame in a city that epitomized it. His ultimate inspiration was Los Angeles itself, at least until he started traveling the world for runway shows and sponsored soirees. It was mine, too, as I found my own niche covering nightlife for LA Weekly, first in the early ‘90s as assistant for this publication’s beloved and feared La Dee Da column (which luminaries like Courtney Love still eulogize to this day in interviews) and then as a columnist myself.

Cory Kennedy, Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie (Mark “The Cobrasnake” Hunter)

With Nightranger, my early 2000s scene column, I sought to convey the debauchery and the diversity of L.A.’s wildest happenings with celebratory, less snarky words than my predecessors and a wider scope that went beyond velvet ropes: drag clubs, punk parties, art shows, red carpets, goth grottos and “hipster” shindigs. But event photos were a harder endeavor, and when I met Mark, I saw the magic in what he was doing immediately. So did the Weekly’s editor-n-chief, Laurie Ochoa (now at LA Times). Soon enough, Hunter was shooting images to accompany my writing in this publication. Eventually, we had side-by-side columns in print – his was called Snakebites and it was a sampler platter from his website – changed from Polaroidscene.com (after a cease-and-desist) to TheCobrasnake.com.

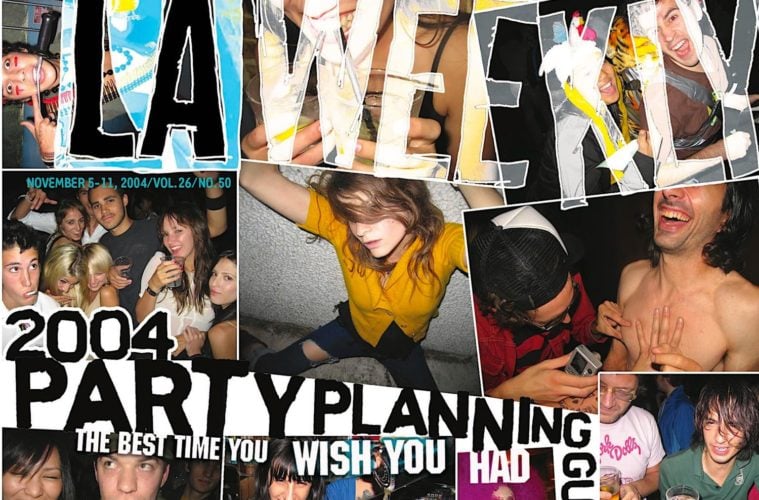

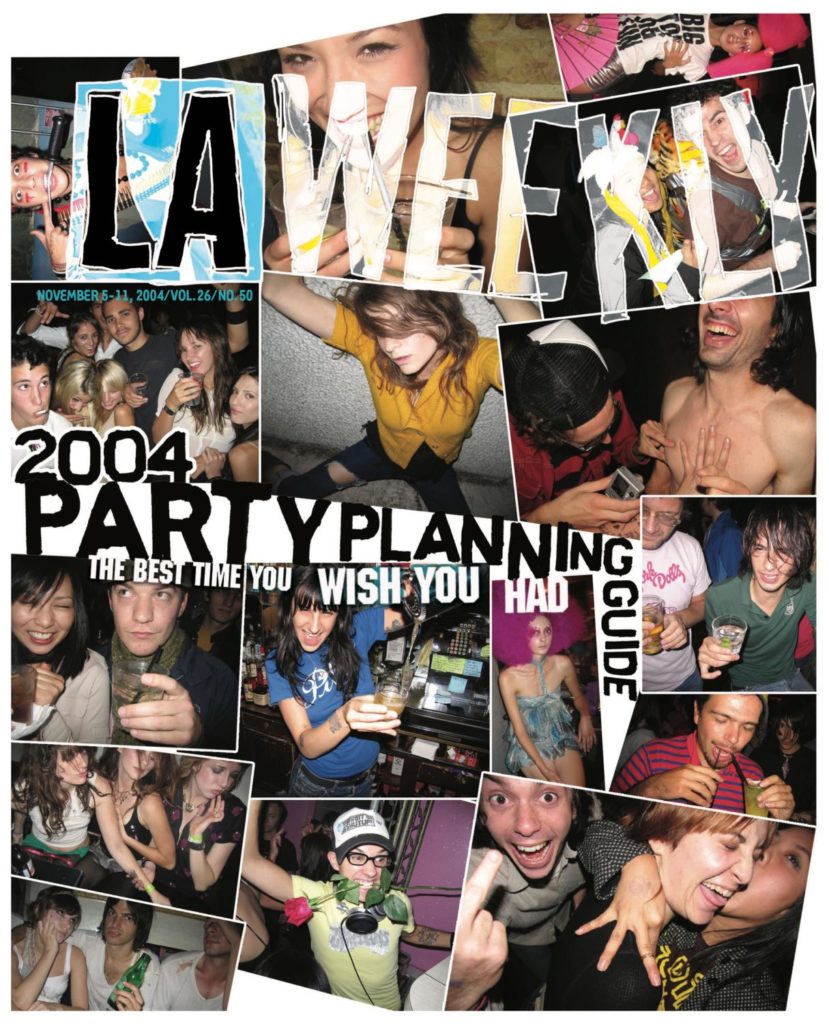

In 2004, only a year after we met and first collaborated, the LA Weekly featured Hunter’s photos in a cover story about the new party renaissance. When he went on to work on other projects and commercial photography a couple years later, I bought a fancy camera and created a new column, “Lina In LA,” to chronicle the scene in the subsequent 2010s. Over a decade later, I’m still writing about nightlife (and much more) as LA Weekly’s culture and entertainment editor.

LA Weekly print edition, 2006

Archiving an Audacious Era

Flipping through Hunter’s recently released Rizzoli book, Y2K’s Archive, is a fuzzy yet flashback-packed experience. To me, it’s like a yearbook or a family photo album, and a curated collection of a specific scene I copiously covered for over a decade, even as I became a new mom during its heyday. My ex-husband was the head chef at Cinespace, the Hollywood Boulevard hotspot that ultimately became the epicenter of “indie sleaze,” as this era is referred to today. I was a regular at Cinespace Tuesdays started by Rachel Dean and DJ Them Jeans, which later became Dim Mak Tuesdays, when promoters Franki Chan and Steve Aoki parted ways and rising star DJ Aoki came to prominence for his record label and riotous turntable sets. This was the Cobrasnake’s homebase. His documentation of what was happening there and around the corner on Cahuenga Boulevard (dubbed “the Cahuenga Corridor” by my friend and LA Times nightlife columnist Heidi Cuda) resulted in a culture-shifting moment that put L.A. clubbing and L.A. lifestyle in general, on the media map beyond movie stars. So much so that actual celebrities (Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan, Hilary Duff) started to flock and rock with the hip cliques, too. That fed into the notoriety obviously, as did the emergence of Facebook and later, Instagram, which probably also killed it. Subversive subcultures rarely survive mainstream popularity, but those who pioneer them can find success in the aftermath if they’re talented and smart. Chan, Aoki and Hunter did exactly that.

Hunter says now is the perfect time to look back on the unfussy fashion and raunchy frolic of it all in book form. “It was a long time coming, actually. I think I should have had one out back in the LA Weekly days, even,” he says. “But now, there’s been enough time to reflect on those images. As you know, we were both around for a very exclusive, exciting time. It’s nice, some people have been reminiscing about our columns in the LA Weekly since the book came out. That was almost 20 years ago. Everything was so different – no social media, no Uber, no smartphones. It was a simpler time.”

Katy Perry and pals (Mark “The Cobrasnake” Hunter)

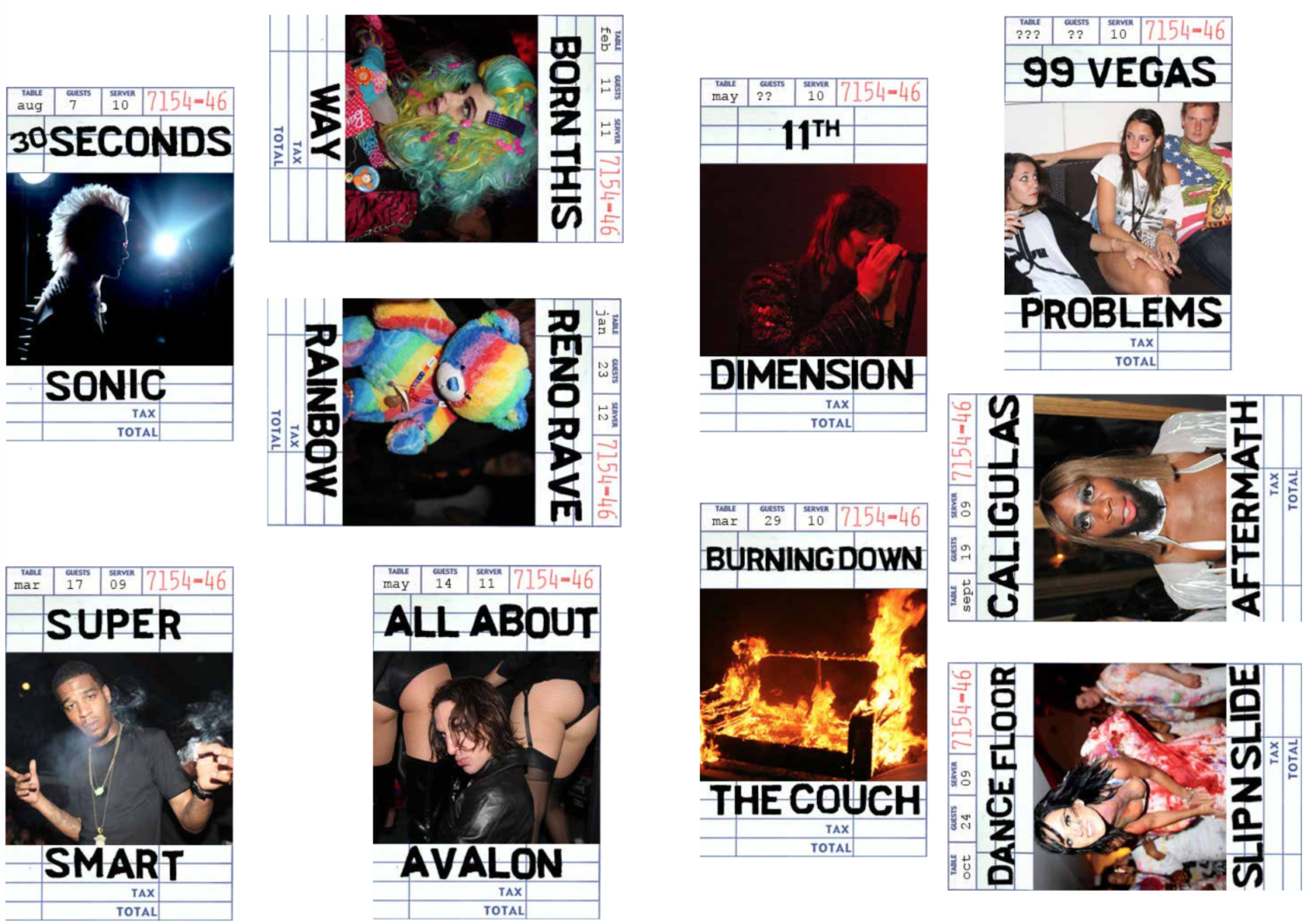

But how did Hunter’s visuals outshine others and ultimately set the standard for what was cool? “I think it was the curation, that’s what people always credit,” he answers. “My blog told a story about the night. It wasn’t just about everybody and everything. It was what I thought was cool, and what I thought was interesting, and it was also the very early indie days. I loved celebrating bands, art and the culture that was so exciting to me and I wanted to showcase that on the blog. It was untraditional at the time because most mass media just put a few photos in a magazine, you know, the rock shots in the front of Spin and Rolling Stone, one image or a couple. But what about the crowd? What about the backstage? What about everything else that paints the picture of what a real show is?”

Hunter’s attention to detail and eye for capturing movement, energy and individual allure served him well as he meandered through L.A. clubs and concerts. He stood out and he attracted those who did, too.

“He was such a character, especially at the time – he was 18 but he looked like he was 35 with big hair and chest hair – we were like, ‘who is this kid?’” remembers Chan, of his and Aoki’s first encounters with Hunter at their early 2000s It spot called Fucking Awesome at the Beauty Bar. “He just looked the part and captured the spirit of what we were doing, and the photos were great. From the perspective of being in the party, you can have an amazing night but you really can’t see the other perspective of what it was like to live it from the outside – you’re in the DJ booth, or you’re on the dance floor or you’re making out with someone or you’re smoking a cigarette in the back. I’d never really seen such a complete picture of what it was like to be at the party. Ever. For the first time we had the full experience of it. He came back the next week and he immediately became an essential element.”

(Mark “The Cobrasnake” Hunter)

Fucking Awesome not only broke down barriers in nightlife musically (they regularly played hip-hop, indie rock, classic rock and even pop in the same sets) but their crowds were the most mixed I’d seen covering clubs in a long time. From Brent Bolthouse-promoted bottle service boites filled with blondes from MTV’s The Hills, to black-garbed ghouls at local goth and fetish clubs to choppy haired moppets at Club Bang and Evil Club Empire events to the new hip-hop clubs that popped up every week in Hollywood to my favorite gay ragers in WeHo, it was a pretty segregated time. It took effort and lots of driving around to cover them all at first.

Indie sleaze was not a label anyone used back then, even if it’s now being touted as a bonafide retro trend by the likes of Vogue. Whatever you call the scene, it definitely brought different factions of the city together. Musically, it evolved as blogging became more popular and people started making beats in their bedrooms. DJ bangers started taking precedence over rock anthems, birthing a genre that was eventually dubbed “blog house,” as it incorporated the simplicity of the electroclash trend from a decade prior with rave elements from even earlier than that. As a former raver who did the map points and illegal warehouse hunts in the early ‘90s, and a fan of Berlin beatsmith Larry Tee and the minimalist electro club scene he led out of New York, it was interesting to see these movements reimagined as everything became new again in L.A. Cobrasnake, Chan and Aoki were on the forefront of bringing these elements to a new generation, and it was amplified and perfected by the internet like never before, ultimately becoming a world-wide phenomenon.

Steve Aoki (Mark “The Cobrasnake” Hunter)

Sleep When You’re Dead

Hunter’s book and its representation of the era is “nostalgic to say the least,” says Aoki, who’s not only a top DJ where he now lives in Las Vegas, but an accomplished producer, and the subject of a Netflix bio-doc about his life. “It was definitely the birth of ‘Steve Aoki the DJ.’ Being in L.A. having Cobrasnake documenting every single thing I did, it made me more recognizable, not just as a DJ but as a cultural figure in the world in which we existed, you know, that bubble. It was what pre-social media looked like for club kids – how we thrived, how we communicated and socialized, and connected across the globe.”

“I think about the importance of these little pockets around the world and how we linked together, and we supported each other back then,” Aoki adds. “Mainly, and specifically the French alliance with Ed Banger. Pedro Winter/Busy P and his whole community in France, coming together with the Dim Mak community, it really was this kind of exponential calculation that occurred.”

DJ AM, Aoki, Hunter and the Ed Banger crew (Mark “The Cobrasnake” Hunter)

Winter, who started as Daft Punk’s manager, went on to found the electronic music label Ed Banger Records, signing artists like Justice, Cassius, and more. After spearheading the trend of musicians as DJs, featuring bands such as Interpol, The Killers and Mickey Avalon on the decks at their first clubs, Chan and Aoki quickly embraced more techno-tinged sounds at their clubs and Banger’s roster was tops. When they parted ways, Chan went on to do a competing night called Check Yo Ponytail and started his own marketing agency IHEARTCOMIX, while Aoki did a host of clubs around town, most memorably with his friend DJ AM. He also got into remixing and producing, creating music with Moving Units Blake Miller under the banner Weird Science, and releasing his own DJ mix album, Pillowface and His Airplane Chronicles in 2008. From there, his credits and his touring history is dizzying – collabs with the likes of Will.i.am, LMFAO, Lil Jon, and Diplo to name just a few, and appearances at every major festival in the world. He’s a bonafide superstar with charting hits and Grammy nominations, and to hear him tell it, his buddy the Cobrasnake was a big part of his success early on.

“It would have been different. Mark had his own audience and they had this affinity to L.A., social culture, lifestyle culture, the way people dressed, the way people looked,” Aoki recalls. “Music is definitely the connective tissue for what culture is, but there’s so much more that goes into it – the lifestyle behind the music. Mark documented it really well.”

Jeremy Scott (Mark “The Cobrasnake” Hunter)

As I’ve written before, the first time I met Hunter was in the VIP section of Coachella in 2003. Clad in fitted, Dayglo jogging short-shorts, sweat socks and a matching terry cloth headband, he was a site to behold. But what I really noticed was his ability to hone in on the most charismatic fest-goers, not only snapping their ensembles, but their essences, sometimes in just a few seconds. When he asked to take my picture, I was flattered – I made the cut – and like everyone else, I was excited to go to his website the next day and see my image alongside the beautiful/bodacious party people.

His site was narrative entertainment and at one point, we all wanted to be in the story. He was forging an exciting new frontier, as the pre-Instagram, post-paparazzi zeitgeist was priming itself for something bigger. It was at this time that LA Weekly debuted its own slate of blog content, including party girl collective reports I contributed to, called The Style Council. We had no idea how big blogging and social media would become or that technology would take over to the extent it did. Imagery has always helped define culture, but the accessibility that computers and smartphones would bring to our interactions was unfathomable back then, not to mention the damage it would do to real media.

Jeffree Star and friend (Mark “The Cobrasnake” Hunter)

The Big Picture

Beyond the clubs and the festivals, sponsored soirees – in the desert during Coachella, at South by Southwest, at Sundance, etc. – became more and more a part of the aspirational amusements people wanted to voyeuristically ogle through an insider lens like Hunter’s. Swag and celebrity started to outshine the nitty gritty nightlife stuff, but he kept his eye steady, shooting the big names (Kim Kardashian, Katy Perry, Lady Gaga and Kanye West are seen in his later pics) alongside the nobodies, with an egalitarian enthusiasm. And since everybody knew who he was, he had access that few others could match.

Publications like Anthem, Filter, Vice, Urb and Paper (the latter three, outlets I wrote for alongside freelancing for LA Times and the Weekly) published their own scene-driven photographic spreads, viewing them as complementary components to written journalism online and in print. The coverage conveyed the street chic and messy mystique of the time, and the marketing potential. Vice in particular, honed a similarly glam-trash aesthetic with its magazine, which evolved and grew over time via its TV channel. As online platforms began to take shape, branding became more important than ever, and media outlets began hosting their own big bashes. The practice continues today, even as magazines like the aforementioned are either hanging by a thread or long gone.

Franki Chan (Mark “The Cobrasnake” Hunter)

Like Aoki with his record label, Chan tapped into the power of marketing with IHEARTCOMIX, the logo of which was on all the early flyers – remember actual paper-printed flyers? — alongside Dim Mak and The Cobrasnake’s URL. In 2006, Chan recalls his first solo Comix event with Peaches, She Wants Revenge, Uffie and Simian Mobile Disco at SXSW. I remember it as well: not only did I deejay a few events that year myself, but I covered the festival for LA Weekly.

Today, IHEARTCOMIX is one of the most successful creative marketing and content studios in the business, working with everyone from Disney and Marvel to Interscope and Beats by Dre. Many of the young revelers who knew Chan as a promoter are now in positions of power in the entertainment industry and the connections have served him well. As technology and PR progressed, it’s elevated things to a more sophisticated level, and Chan says he saw things in “whole branding package” terms early on. “Ever since I was a kid, I was obsessed with movies, comic books, TV, and music, via MTV,” says Chan. “That’s all I absorbed all the time. So even when I was promoting a show, whether it was a punk show or a nightclub, my mind was very wired to think about things like a movie or like a comic. That approach really stood out because it was different from how most people were doing it.”

Diplo, MIA and the Misshapes (Mark “The Cobrasnake” Hunter)

Photography has always and will always be a big part of marketing a lifestyle to consumers. As Hunter’s work became a familiar part of the pop culture landscape, he started to score big gigs that took him out of L.A., including New York Fashion Week. Others filled the gap. NYC’s Merlin Bronques, by the way, had his own photoblog called LastNightsParty, and it was fun to see the two fellows trade off, shooting each other’s cities from time to time. Shadowscene, Rolling Blackouts, Rony’s Photobooth and Polite in Public all came up around this time, providing party images for the millennial masses hungry for more documentation of their exploits to share on then-brand new social media platforms. Dov Charney’s T-shirt company commodified the vibe for the masses, and sold lots of tube socks and T-shirts in the process. None of it was by accident.

“My images started circulating on the internet, and then when brands would be like, what’s the new cool thing, and some intern would point to my blog,” Hunter shares. “I was really sort of resourceful in the way I worked with brands, sort of like a Robin Hood. Anytime I got hired for a job, I would book all my hipster friends. We were getting into the American Apparel nontraditional model aesthetic and that was so special to me because we were taking people out of obscurity, and celebrating them with these campaigns.”

TheCobrasnake.com

Flashing Back

For better or worse, turning everybody, especially unconventional looking people, into models might be the Cobrasnake’s biggest media contribution of all. A new generation of youngsters reared on Instagram and TikTok seem to understand this. The launch party for Hunter’s Rizzoli tome late last year was held at the Dolls Kill store on Fairfax, and he was seen slithering around just like the old days. Chan even deejayed the event, which was packed with Gen-Z kids in Electric Daisy Carnival-style skimpy outfits, face-jewels, and lolita get-ups. Clearly, the 20-year trend cycle is in full rotation and there’s no turning back. Low-rise jeans and visible g-strings, metallic accessories, clashing geometric patterns, Kanye West shutter shades and Dolls’ revamp of the Delia’s brand – all contribute to the nouveau retro enchantment happening right now.

Around the same time that Y2K’s Archive was released last year, a Bloghouse book called Never be Alone Again came out, plus a documentary, Meet me in the Bathroom (based on a book about the NYC music scene in 2001-2011), and a podcast called Date with the Night, celebrating everything aughts. Festivals are also nodding to the era– this Spring’s Just Like Heaven fest is headlined by some of the biggest bands of the early 2000’s including The Yeah Yeah Yeahs, MGMT, Hot Chip and Ladytron, and there’s even a “Cinepace DJs” lineup headed by Them Jeans, touted on the flyer.

(Mark “The Cobrasnake” Hunter)

As for Hunter, after branching out into retail with a vintage store in Hollywood for a few years and creating a fitness crew focused on hiking and health, he now has a side hustle doing property management. When he goes out, he’s still the king of the scene, of course, and his gift for bringing gusto to every snap has not waned whatsoever. He says he’ll be doing more events soon and he probably has more publishing in his future as well. “The archive has over half a million photos… we cut it off at like 2010-2011 for the book, which is sort of when social media took hold and changed the landscape,” he reveals. “There’s photos from 2010 to 2015 that would make another great book.”

Beyond the novelty of millennial hipster hedonism, Hunter’s images exhibit unfiltered joy (both literally and figuratively). They remind us of the past, and for younger fans, they inspire the present. Camera phones were inevitable and social media was growing either way, but the Cobrasnake brand of self-promotion as narrative art encouraged a realness and revelry that’s missing, if seemingly making a more filtered comeback. As his friend Aoki, who’s currently working on everything from NFT’s to clothing and still touring, expresses, “he was really good at grabbing that moment of complete candid rawness, at the most interesting, engaging, vulnerable moments of people’s lives. Super high on the music or super high on drugs or super high on life – whatever it might be, he was there and he did it consistently and created his own subculture in the process.”

Mark Hunter’s Y2K Archive available wherever books are sold and at rizzoliusa.com.

The 2004 LA Weekly party issue cover (Mark “The Cobrasnake” Hunter)

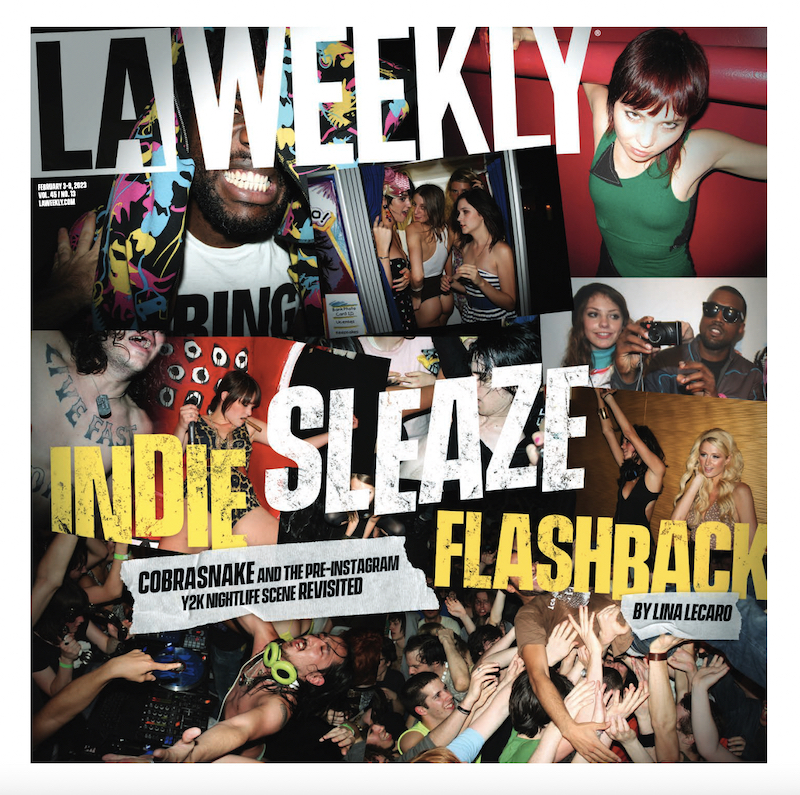

Our 2023 LA Weekly cover homage (Mark “The Cobrasnake” Hunter)

Editor’s note: The disclaimer below refers to advertising posts and does not apply to this or any other editorial stories. LA Weekly editorial does not and will not sell content.

Editor’s note: The disclaimer below refers to advertising posts and does not apply to this or any other editorial stories. LA Weekly editorial does not and will not sell content.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.