PARIS – He lies somewhere between a Zelig of rock ’n’ roll and the great disappearing act of Jacques Brel; his friends, contemporaries, and musical admirers include Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, and Lou Reed. He has acted as his own alter-ego in a feature film alongside Marisa Berenson, and his novels, short stories, and memoirs have been published and translated in multiple languages around Europe. So why, with his four studio albums from three major U.S. record labels followed by nearly 40 more independently produced records, is Elliott Murphy almost entirely unknown in his native America and the rest of the English-speaking world?

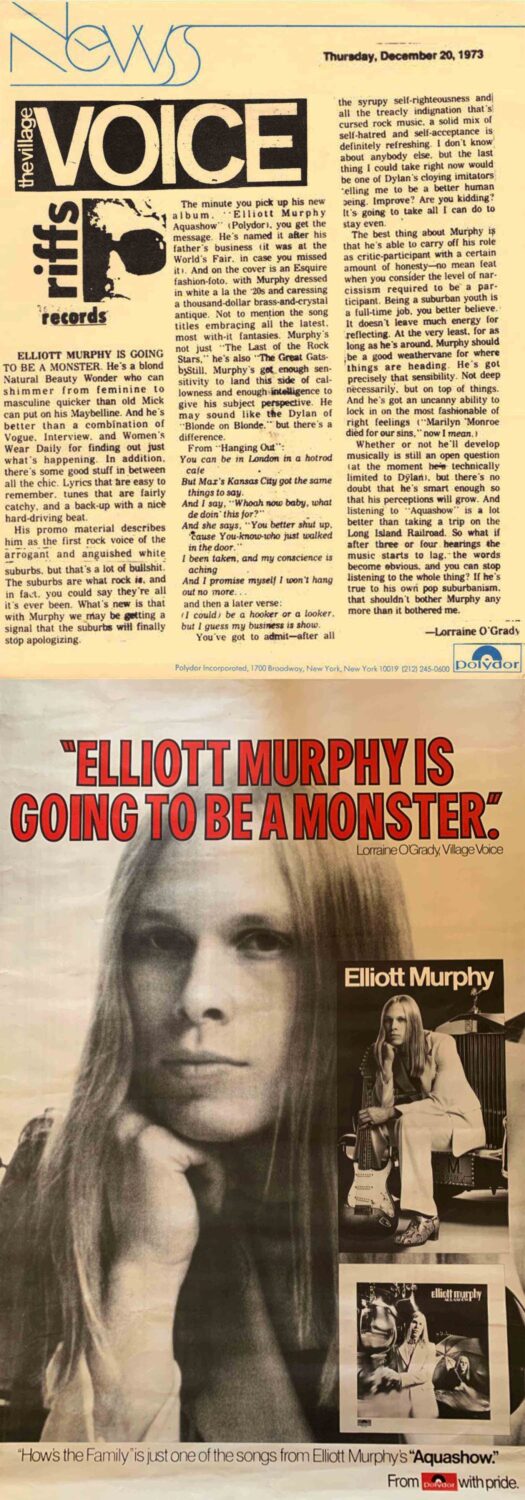

Half a century ago, Murphy’s music was on the radio in the U.S. and he was being called a new Bob Dylan by Rolling Stone, Creem, and other publications that covered the heyday of rock. His first album, Aquashow, was released in November 1973; after a tsunami of critical praise, by early ’74 a Madison Avenue ad campaign had posters of his face plastered throughout the New York City subway system, adorned with this line from a Village Voice review: “Elliott Murphy is going to be a monster.”

Then Murphy slowly began to fade from the scene, before one day disappearing just as abruptly as the popular Belgian singer Brel had done in Paris, in 1966. Brel was at the peak of his career when, at age 37, after farewell concerts at the Olympia music hall, he proclaimed that he had nothing more to give as a singer. And now, to paraphrase the title of the musical that made Brel internationally famous: “Elliott Murphy is alive and well and living in Paris.”

In fact, he is thriving like never before.

Throughout 2023, Murphy, 74, had been celebrating the Aquashow anniversary by continuing to fill concert halls in France, and around Europe, drawing his fans to their feet stomping for encores as he has done since he settled there, in 1989. Indeed, F. Scott Fitzgerald to the contrary, France has long served as a stage for second acts in the lives of American artists, and few today prove the novelist’s dictum so wrong as Elliott Murphy, who traded his life as an also-ran drug-addicted rock star on the fringe in America for rebirth and recognition in France — a success story now running steady for more than 30 years.

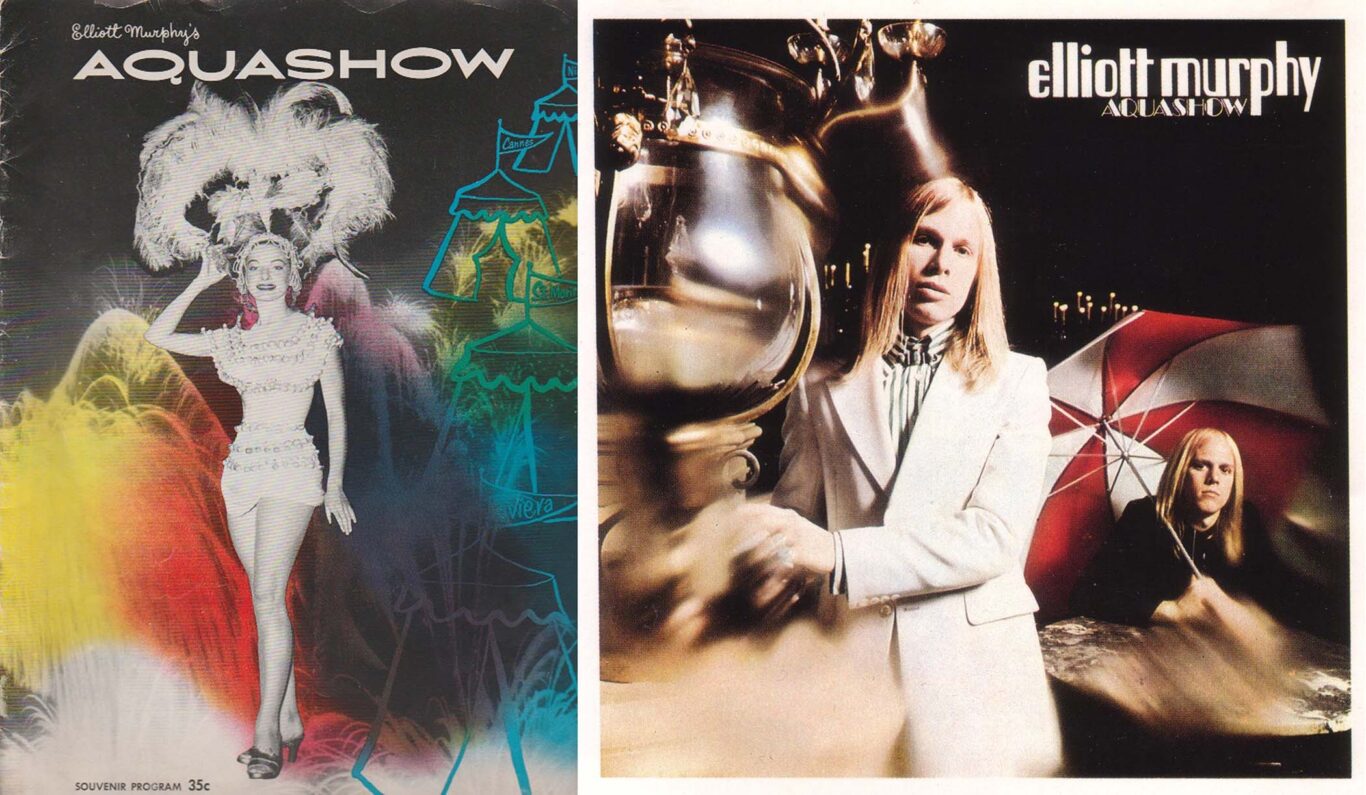

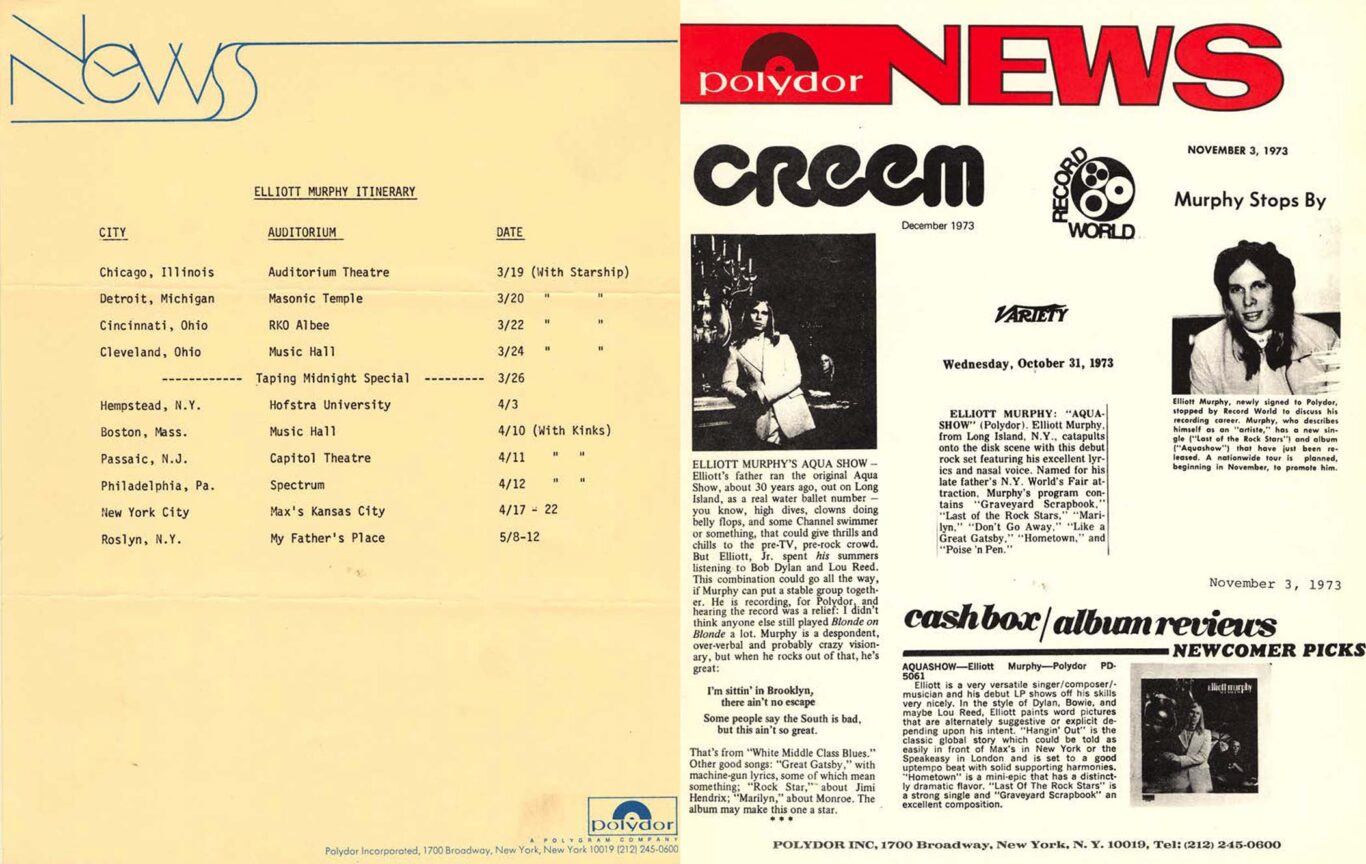

(AQUASHOW PROGRAM AND ALBUM COVER FROM ELLIOTT MURPHY COLLECTION)

After seeing him at one of his annual birthday gigs at the New Morning venue, in Paris last year, I had to dig deep to figure out if age had stripped anything at all from Murphy’s life and performance, as it has from so many of his contemporaries. My conclusion? Like the old wine of the cliché — a drink Murphy has not touched for nearly 40 years — he has improved with age.

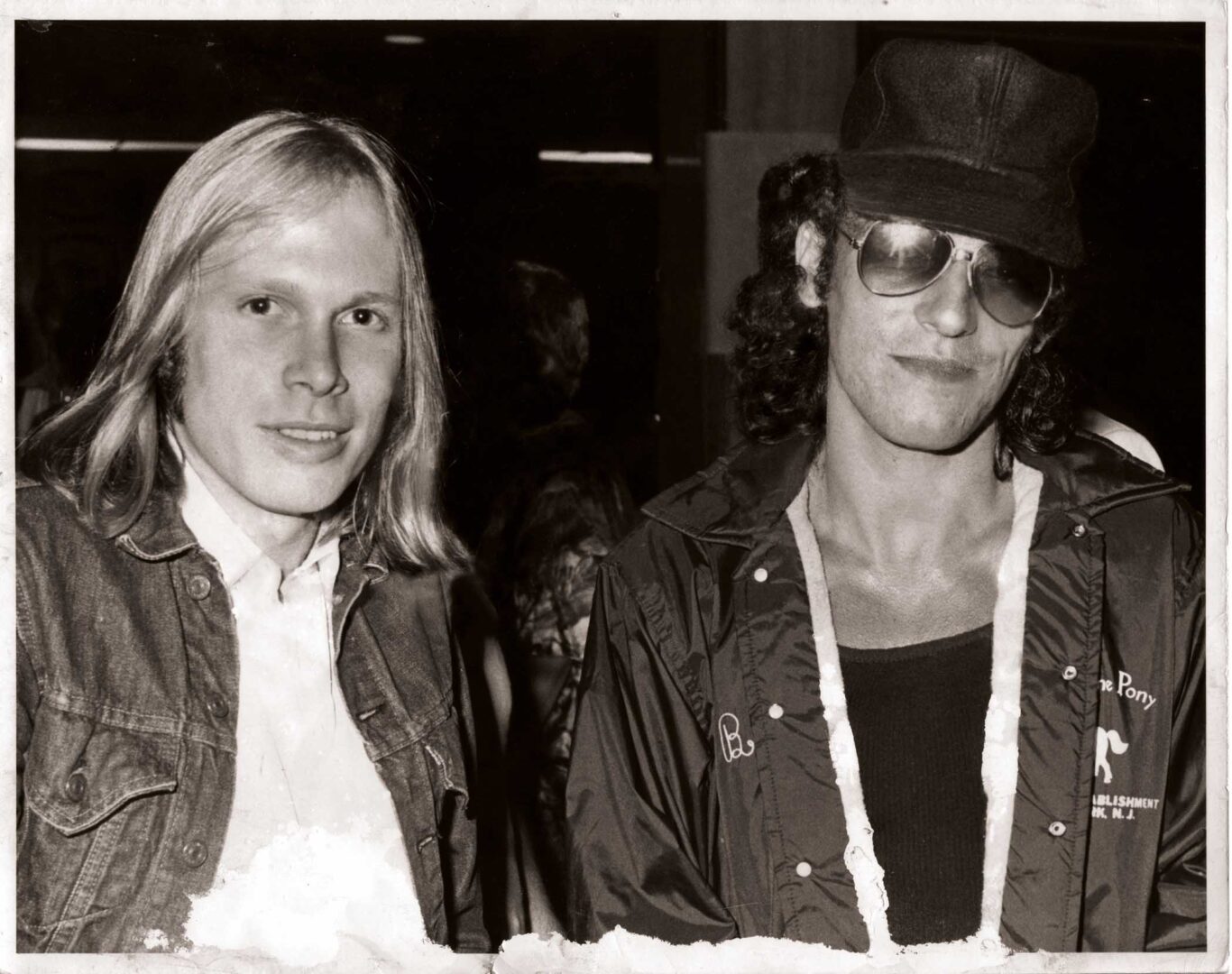

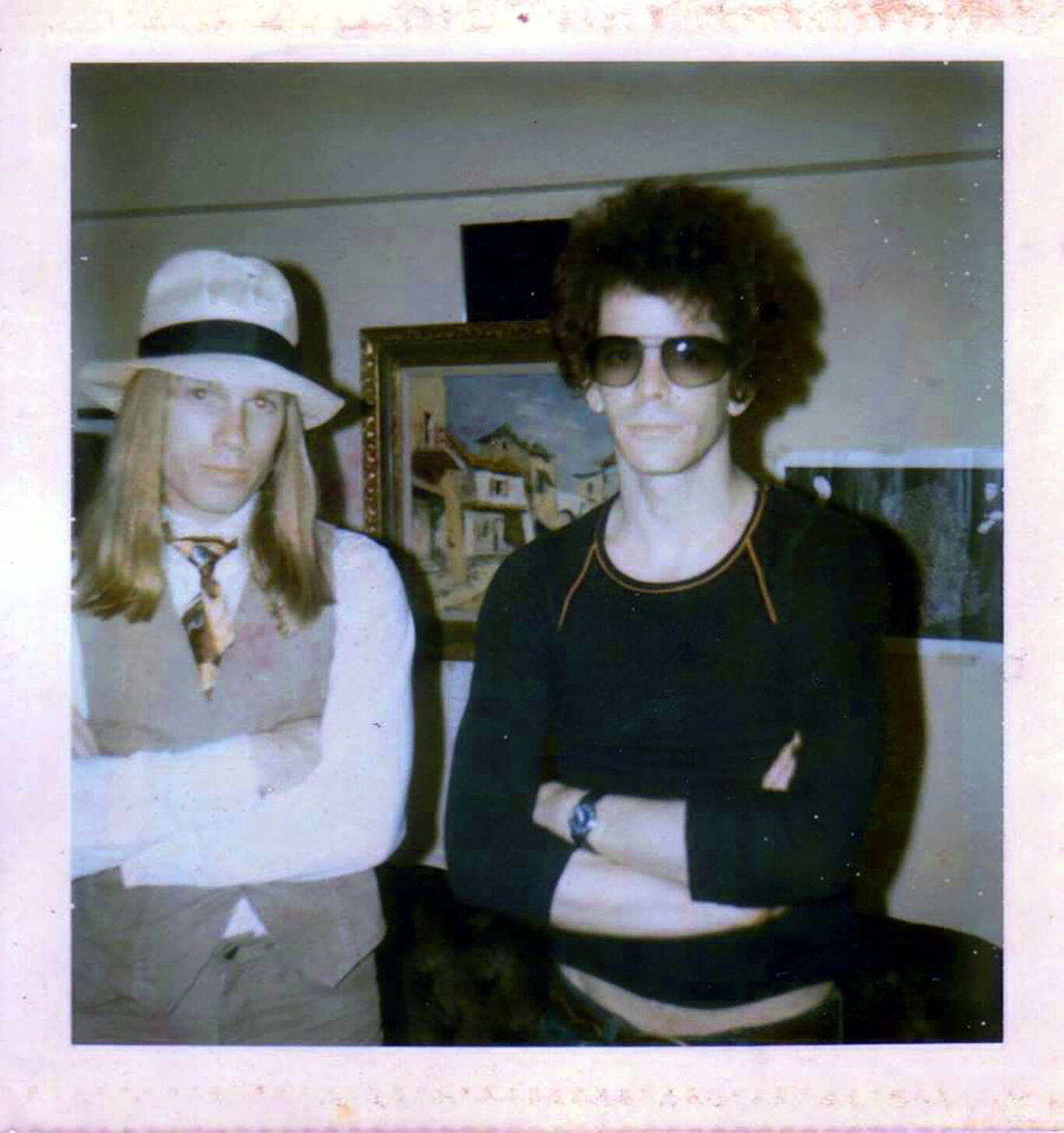

In a 2015 documentary film about Murphy’s life, made by Spanish director Jorge Arenillas and called — naturally — The Second Act of Elliott Murphy, Murphy’s Long Island friend and contemporary Billy Joel said, “Elliott was what we call a career artist,” adding that Murphy was “dedicated to not being commercial for the sake of selling records. He was very true to his art and had integrity and was able to survive when a lot of other people just left the business altogether.” And proving that among the cognoscenti, Murphy is not entirely forgotten in the land of his birth, in 2018 Joel inducted Murphy into the Long Island Music and Entertainment Hall of Fame, where both Joel and Murphy’s friend Lou Reed — who died in 2013 — are also inductees.

In my efforts to understand the why and how of the Elliott Murphy story, I button-holed him after that birthday show last March and asked if we could meet up for an interview. We met and communicated several times since then, and I also attended his 50th-anniversary career gig, in October at the New Morning, which proved irrefutably — to me and all present — that the performer is still in possession of all the talent he ever had. And then some.

An inkling has grown on me that maybe Murphy, who never had an international hit song and never became a million-seller as the record companies hoped, was also never a “has-been.” Rather, at the heart of darkness in his career, he chose, like Brel, to seize his own destiny and take revenge by living well and remaining true to his artistic vision.

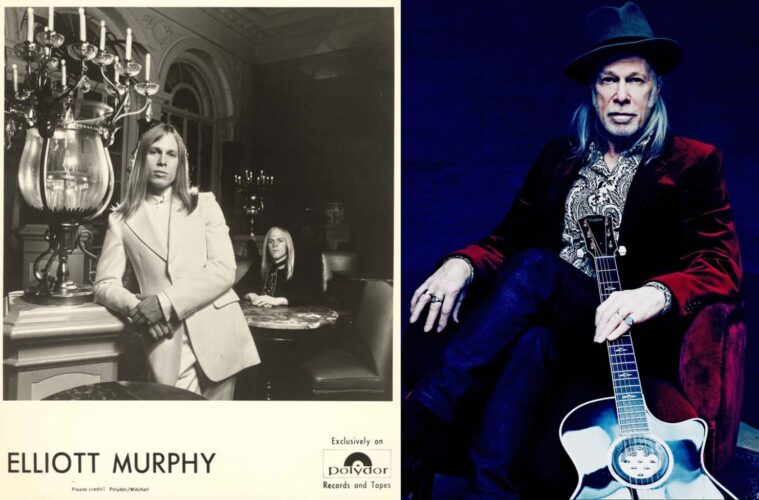

Our first interview took place in a brasserie in the funky Bonne-Nouvelle quarter, not far from the five-floor walk-up apartment with a view of the Eiffel Tower where Murphy has lived with his actress wife, Françoise Viallon, since he first settled in Paris. He arrived for our talk looking his usual stage self, wearing one of his iconic hats from which his signature long, straight blond hair falls to his shoulders. (He buys the fedoras and homburgs from Anthony Peto, a celebrated British-born, Paris-based hat-maker whose shop is close to Murphy’s home.) That stage persona was, from the beginning, a strong part of Murphy’s self-definition as an artist. “That played perhaps a larger role in his music than other musicians’ personas,” says Peter K. Siegel (the A&R man at Polydor who spotted Murphy and produced Aquashow) in a video call. “I mean, he had this character.” Both Joel and Springsteen concur in the documentary: “He was a great-looking guy, he looked like a rock star,” recalls Springsteen. “Beautiful blond hair and a great face, he was a real dandy, he dressed spectacularly.”

Murphy speaks in a deep, warm Long Island accent, and puts on no airs. During our first meeting it was mid-afternoon, with the busy sidewalks of Paris sparkling in rare sunlight as we spoke over cappuccinos. One key to Murphy’s Phoenix-rising-from-the-ashes tale is that in addition to the previously mentioned wine, he has not touched any alcohol, or drugs, for nearly 40 years. “Drugs?” he says, when I broach the subject. “My final statement about being an expat here: Jim Morrison lasted three months in France. I’ve been here 32 years. Who’s the winner?”

(TOP: MURPHY PRESS KIT FROM POLYDOR, ELLIOTT MURPHY COLLECTION / BOTTOM: SUBWAY POSTER FROM ELLIOTT MURPHY COLLECTION)

But that’s a closing declaration. Let’s return to 1973, when Murphy appeared out of nowhere, after very little folk club, bar scene apprenticeship. A taste of something big to come showed up in the July 1973 issue of Penthouse, when Bud Scoppa, a journalist for all the major music publications of the time, wrote a brief review of a show he had seen earlier in the year: Elliott Murphy and his band on a bill with the New York Dolls, at the Mercer Art Center. Scoppa compared Murphy to the Dylan of both Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde; a several-monthslong deluge of similar reviews followed once the album was released. Polydor was not prepared.

It was Paul Nelson’s review, in the January 31, 1974, issue of Rolling Stone, that put the final crown on the Dylan comparison, calling Aquashow “the best Dylan since 1968.” But already throughout that fall, the tremors had been reverberating everywhere: Virtually every writer had been comparing the album to the Dylan of Blonde on Blonde. Possibly the first of these was a long Newsday article on September 30, by Dave Marsh. In November, again in Newsday, Robert Christgau gave it an “A” rating and also drew parallels to Blonde on Blonde. Another review, by Tom Nolan in the December issue of Phonograph Record magazine, had the headline: “A suburban Freeze-dried Dylan.” The Village Voice piece on December 20, by Lorraine O’Grady, began with the “monster” quote used on all those NYC posters. And in the January 1974 issue of Phonograph Record, Scoppa wrote a long feature about Murphy, saying that the musician had “a talent and an approach to rock & roll that is uniquely universal. He has all the makings of a star.… ” The deluge came to a head in late February, with a two-page review of the album in the New Yorker, by Ellen Willis — a one-time partner of Christgau’s — who also compared the album to Dylan. Reviews made it into Creem and Melody Maker, and there was even high praise in The New York Times.

All the media attention had finally made Polydor decide they’d better pay more attention, and in March ’74 they sent Murphy out on tour with Jefferson Starship and the Kinks. “With the critics, that album was about as big a success as you can have,” says Murphy. “It was not a huge commercial success; it did sell some. We did get a lot of radio play. But everyone said the problem was Polydor and their distribution. We’d go play up in Boston and then we’d find out no albums were available.”

In our video interview, Polydor’s Siegel concurred: “When the Rolling Stone article came out, they were kind of caught short-handed. I think that was the beginning of why [Murphy] left Polydor.” Murphy followed up with three more albums with two other major labels, RCA and Columbia. When I noted to Siegel that Murphy didn’t do much better with them, the producer agreed, saying, “He burned through more major labels in a shorter time than anyone I ever heard of.”

Murphy’s second album, Lost Generation, with RCA, should have been the break-out: It was recorded at Elektra Studios, in Los Angeles, and produced by the legendary Paul A. Rothchild, who had guided, cajoled, and, in the words of Jac Holzman, founder of Elektra Records, “perturbated” the Doors through their first five albums for the company. Rothchild had also done Janis Joplin’s posthumous Pearl, for Columbia. Murphy’s album featured some of the greatest backing musicians of the time: Richard Tee, on piano; Sonny Landreth, on guitar; and Bobby Kimball, on harmony vocals. But again, it failed to take off, though even in our interview Siegel called the title song “A killer!”

In retrospect, that “lost generation” reference can be seen as foreshadowing the future life of salvation for this man, whose favorite writer remains Fitzgerald, another creative artist who suffered from “early success.” “It was too much too soon,” says Murphy. “I wasn’t ready for it. I was really terrified to do a second album. My first album was compared to Blonde on Blonde, so what am I supposed to do now? What are people expecting from me? Who am I?”

(ELLIOTT MURPHY COLLECTION)

In a way the stars were already aligning toward the Paris expat life, even before that. “In the Rolling Stone review for Aquashow,” Murphy says, “Paul Nelson called me a ‘spiritual descendant’ of F. Scott Fitzgerald and said that I seemed to ‘… want something better, something with the glory of F. Scott and Ernest’s Paris.’” Murphy also faced direct comparison with Springsteen, as the Boss’s second album, The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, was reviewed in that same issue of Rolling Stone, with a comparison to Dylan in regard to Springsteen’s debut album. Murphy and Springsteen met at one of Springsteen’s shows at Max’s Kansas City and became lifelong friends, and Murphy has performed with Springsteen for Springsteen’s arena shows in Paris. “In my opinion, Elliott had hit songs,” Springsteen says in the documentary. “Rock Ballad, Last of the Rock Stars — to my mind, these were hit songs. They just didn’t end up on the Hit Parade.”

Murphy’s third album, Night Lights, was released in 1975 and produced by Steve Katz, a former member (along with Siegel) of the Even Dozen Jug Band and a founding member of Blood, Sweat & Tears. This was with RCA again, and it too had an exceptional lineup of musicians, including guest appearances by Billy Joel, Michael Brecker, and Jerry Harrison, later of the Talking Heads. It was also received well by the critics. “In 1973 and 1974 it seemed to many of us in New York,” wrote Marsh in his Rolling Stone review of Night Lights, “that it was a tossup whether Bruce Springsteen, the native poet of the mean streets, or Elliott Murphy, the slumming suburbanite with the ironic eye, would become a national hero.”

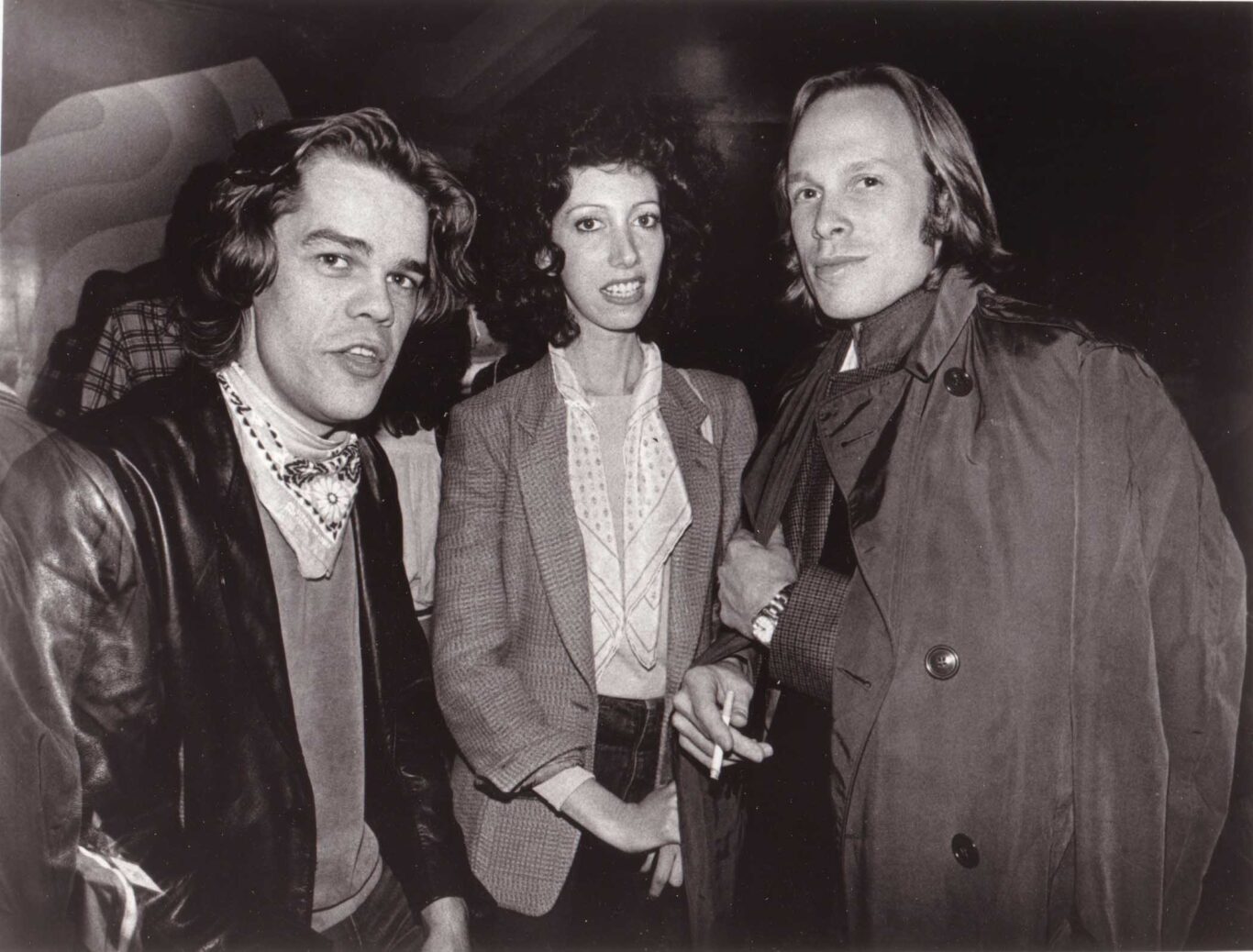

Yes, Murphy’s early efforts were all about the suburbs, and seeking a better life. They were also about looking back at his own life and his father’s early death — when Murphy was just 16 — and wondering how to heal the pain. Art was one way, and he remained true to it. Another way, unfortunately, was the life of excess of the rock star that he henceforth devoted himself to. After being offered his first line of cocaine by David Bowie in mid-1974, Murphy fell deeply into drink and drugs, in what he described to me as “my 10-year voyage of addiction.” He hung out or crossed paths with Reed, Patti Smith, Springsteen, Frank Zappa, David Johansen, Bowie, Mick Jagger, and other luminaries, and became what he calls “a semi-regular at Studio 54.”

Above all, Murphy found himself progressively losing touch with reality. Even so, it wasn’t until he released his fourth album at a major label, in 1977, that he finally hit rock bottom. This last one of the decade, Just a Story From America, with Columbia, was recorded (with a touch of irony) in London and featured such backing musicians as Phil Collins and one-time Rolling Stones guitarist Mick Taylor.

In a revealing moment in the documentary, Murphy says, “Everyone loved the album. ‘Drive All Night’ they were sure was going to be a major hit. But I think even before the promotion for that album was finished, I just ran out of energy, and I lost my faith. And I stopped a tour in the middle of the tour [35 shows across the U.S. and Canada, from February to May 1977]. I was so afraid, I think, of being disappointed again. It was like, ‘Before this fails, I’m going to stop it.’”

This was a key moment in Murphy’s life and career, which also raises the question of how not living up to the early promise of superstardom that his friend Springsteen had found was, perhaps, not so much a failure to succeed as a personal choice. Everything from that moment onward, over the decade of the 1980s, would point in a single direction: Murphy’s second act, in Paris.

Clues and suggestions about this moment of transition can already be found in the 2020 feature film Broken Poet, in which Murphy acts as his fictional alter-ego, Jake Lion, who has disappeared in Paris and faked his own death. The film was made by Spanish director Emilio Ruiz Barrachina and featured Marisa Berenson, Joana Preiss — who plays a journalist at Rolling Stone — Viallon, and Academy Award–nominated actor Michael O’Keefe. Viewers also got Springsteen and his wife Patti Scialfa, as themselves, who are supposed to have been friends with “Jake Lion” before his disappearance.

The film is based on a short story Murphy wrote in 1985, titled The Lion Sleeps Tonight, published in a Long Island magazine called Music & Sound Output. It is difficult not to apply Springsteen’s words directly to Murphy when he says, in Broken Poet, that Jake disappeared “just as he was becoming really successful. It’s not for everybody, but he’d done all the hard work…. And once he got there, for some reason, he slipped off the map.” Scialfa then adds, “He didn’t like what came along with it — the fame. I think fame felt very disruptive to him and made him go really inward.” The journalist character notes an interview with Jake during which he said, “It was easier to confront a failure than to deal with success.” Springsteen then adds the most pertinent point: “He was just more private than most. Considering for a job where you are putting yourself out in public on a daily basis … I had my struggles with it, and most musicians or artists do. But at the same time, I was determined, I felt our band was good enough that we deserved an audience. So I followed that path, and I just think it was just a lot easier for me than it was for Jake. For some reason, Jake, whatever his inner demons were, or whatever you want to call them, he was a lot more ambivalent about the kind of success he was able to have.”

Back in 1977, after breaking down during the tour for Just a Story From America, the real-life Murphy and his managers made a few ill-fated efforts over the following year to revive his career. The final blow came at the end of 1978, when Murphy learned that Columbia did not pick up his option for another record. By 1979, broke and owing money to the IRS, he finally “disappeared” completely, returning to live at his mother’s apartment to “try to figure out what the hell happened to me,” as he explains. “I like to say I went from living for months at a time at the Beverly Hills Hotel to sleeping on a cot in my mother’s kitchen. … When the roof fell in on me, when I fell off that rock ’n’ roll mountain, it was very tough. Elvis was dead, disco was taking over, and the punks were screaming. And singer-songwriter was a dirty word.”

By 1985, the year he wrote the short story and after a few independently produced albums, Murphy found himself in his late 30s, washed up and washed out, feeling out of sync with the MTV generation. That is the year he not only decided to kill the addictions — rather than himself — but also pumped up the courage to return to school, not as an aging rocker but as a mature student with literary ambitions doing a degree in English at State University of New York, Empire State College.

Murphy supported himself as a clerk in a Manhattan law office but continued gigging here and there, recording independently, and writing songs, as well as publishing fiction and journalism. “They were a music business law firm,” he explains. “I was a paralegal, working for this litigator, and across the hall from there was a kind of well-known entertainment lawyer. And one day he came over to me and he said to me, ‘Hey, listen, I have all these clients coming in here and saying there’s this secretary sitting over there that looks like this singer-songwriter Elliott Murphy.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, that’s me.’” The lawyer asked what Murphy was doing there, and Murphy said things were tough in the music business, he needed a job, and he could type. But he also said he was thinking of becoming a lawyer himself. The lawyer, Murphy says, responded in a foreboding voice that Murphy imitated, saying: “‘Don’t do it! Don’t do it!’ It was the voice of the Charles Dickens Christmas Carol future. ‘Don’t do it!’ So I didn’t.”

(MURPHY PRESS KIT FROM POLYDOR, ELLIOTT MURPHY COLLECTION)

Instead, Murphy devoted himself to his studies, and, more heavily than ever, to writing. His love for literature was cultivated in childhood; a big moment arriving after he saw the film East of Eden, which led him to John Steinbeck. From there, he discovered William Saroyan and others. “The first and the greatest road book in my mind is Huckleberry Finn,” he says. “I read that and then a little later, I guess, I got into the Beats and Jack Kerouac. And then I discovered F. Scott Fitzgerald. The Great Gatsbyopened a marvelous world. I always say Ernest Hemingway was the Great American Novelist, but Fitzgerald wrote the Great American Novel.” The penultimate song on Aquashow was called “Like a Great Gatsby,” but was changed to “Like a Crystal Microphone” in the U.S. edition to avoid violating copyrights on the novel.

In some ways, these patterns were established when, as a boy, Murphy had a story published in a school magazine. Writing has always run parallel with music throughout Murphy’s life, even directly influencing the songs themselves. “Literature is my religion and rock ’n’ roll is my addiction,” he tells me. “It has really held true all these years. I’ve always used both visions, both worlds.”

In 1972 Murphy began writing his autobiography, to which he gave the title Seeds of Discontent, although it would take until 2019 to finish the version he eventually published with his own Murphyland Books company. The book was renamed after his last studio album, Just a Story From America, and was translated into French with this title, as well as into Spanish with the title The Last Rock Star. (Murphy’s first published piece of writing was the liner notes for 1969: The Velvet Underground Live, which came out in September 1974, a commission from Nelson, whose Mercury label released the Velvets’ album.)

A bigger writing break came just as his music career hit the skids, thanks to a chance 1980 meeting in the street with Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner, whom he had known for years. Asked by Wenner what he was up to, Murphy said, “Not much,” except that he was writing some poetry and stories. Wenner ended up publishing some of the poems and interviews, including one with Tom Waits, for whom Murphy had opened the previous decade. In the year-end 1980 double issue of Rolling Stone,Wenner published Murphy’s short story “Cold and Electric.” The tale was inspired by Fitzgerald’s Pat Hobby Stories, which Fitzgerald wrote when he was on the skids in Hollywood. Murphy’s story was eventually published in French as a novel, by the literary publishing house Gallimard.

For all of these strands of artistic production, Murphy was awarded, in 2015, the title of Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters (Chevalier de l’ordre des Arts et des Lettres). He explained to me that there are three levels to this distinction: “There is chevalier, you are a knight. Then you are an officer. And then you’re a commander. Patti Smith is a commander. So I guess I gotta take orders from her, if she shows up.”

Murphy says that when he took the job in the New York law office, in 1985, he thought “it was the end.” He later decided “it was the best thing I ever did.” The firm was transitioning to computers, and he was sent for training and ended up using the computer for all of his work and writing. Equally important, there was a telex in the office, with which he was able to communicate with European promoters and agents, helping him plan the next phase of his career.

That move was linked to a memory, an image that had stuck in his mind. Murphy had done a show in Paris in 1979 at Le Palace, one of the “in” nightclub-cum-concert venues of the period, where he was astonished to discover that he was received like a star. His song Anastasia, from the 1977 Just a Story From America album, had been a hit in France. He concluded that if his record companies had done little in the U.S. to make sure his music was distributed and known, their European counterparts had done a great job.

“I did like six encores!” he exclaims, his eyes appearing to see the moment again. “And then when I went to a place like Spain, people would be there, or when I went to Italy and Belgium — but not the U.K. The rare exception. Most American artists go through the U.K. and then to the continent.” Murphy remains amused that for an artist whose lyrics and writing are so important, he is virtually unknown in English-speaking countries.

He returned to Le Palace again in 1982, for another successful show. About a year after he earned his Bachelor’s degree in English from SUNY, in August 1988, he moved to France. On his first day there, Murphy awoke to the sound of military jets and parades, in a grand celebration of the 200th anniversary of Bastille Day, on July 14, 1989. A fitting reception for his new life in the promised land. He met his future wife that same year, and the next year his son, Gaspard, was born. (Gaspard, now 33, is also a successful musician and producer, and regularly plays with and produces his father.)

Murphy’s intuition about his second act has proven right: France, he has found, is one of the best places in the world for a recording artist. He has benefited not only from the country’s excellent healthcare system — noting that most of his musician friends in the U.S. need day jobs just to pay for medical coverage — but also from France’s generous employment system for performers, called “intermittence,” which ensures a monthly salary to a working performer even when the gigs are thin. Above all, he found a culture that had a different, more respectful attitude to the work of its artists.

It was a long road from the Fitzgeraldian story of his roots to the second act of Elliott Murphy, but the clues to the direction he would take lay everywhere throughout that difficult ascent from boyhood to finding his true calling. Born into a wealthy family, Murphy had show business in the blood. His father, Elliott Murphy Sr. — to avoid confusion, Elliott was called Jimmy during his childhood and teenage years — was a self-made show-business entrepreneur who ran a successful outdoor water extravaganza during the 1950s, called The Aquashow. Located in a giant amphitheater built on the site of the 1939–1940 New York World’s Fair, at Flushing Meadows, in Queens, the venue offered synchronized ballet swimming, circus acts, and fireworks, as well as comics such as Henny Youngman and orchestra leaders including Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway.

Elliott Sr. had grown up in Brooklyn as the son of a poor Irish immigrant blacksmith-turned-garage-owner, who lost everything during the Depression. But he had better luck than his tradesman father, and eventually bought a big house in Garden City, on Long Island, where “Jimmy” grew up with his brother, Matthew, and his sister, Michelle. Elliott Sr. soon added a Cadillac and his own table at Sardi’s, with his name on a brass plaque above it. When the newly constructed Long Island Expressway cut off direct access to The Aquashow, it cost him business and he closed it down. Not the kind to be discouraged, though, he shifted focus, buying a floor-through restaurant on top of the Franklin National Bank building overlooking Roosevelt Field, on Garden City’s eastern border, which he called Elliott Murphy’s Sky Club.

(ELLIOTT MURPHY COLLECTION)

In the memoir Just a Story From America, Murphy describes the restaurant this way: “[It] was the epicenter of Nassau County’s intense political activity and New York governor Nelson Rockefeller, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, and other dignitaries of the time often came to speak at exclusive men’s only Sky Island Club lunches. I have a somewhat shocking photo of a striptease artist performing at one of these lunches right in front of Bobby Kennedy and my Dad; both of them looking quite content to be there!”

But tragedy struck when Murphy’s father died, at age 48, of a massive heart attack in his bedroom, and his panicked mother called Jimmy to help. The memories still haunt him today. “If my father had lived,” Murphy says in the documentary, “I don’t think I would have become a songwriter, because I think my songs have always been about looking to find him again.” Even his earliest musical influences came from his father, who “seemed to be able to play any song on the piano,” though he had never taken lessons. As a child, Murphy was surrounded by musical instruments, his parents soon buying him his own plastic ones.

After her husband’s death, his mother, Josephine, was unprepared to run the business, and the restaurant soon went bankrupt. The Cadillac and the beautiful home had to go. To support her three children, she ended up working as a salesperson in a discount jewelry store on the first floor of the same building where the restaurant had been. Elliott left high school the following year, going on to attend Nassau Community College at night, but he hated school. He took his revenge in music, with his band The Rapscallions, winning the New York State Battle of the Bands in 1966. That led to nothing, though, as Elliott was the only member interested in pursuing the prize of a recording contract and participation in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade. Within a year of his father’s death, his mother married a construction worker named Slim, who Murphy did not like. He had to get away.

His father’s insights left a lasting impact on the budding musician. “He taught me, number one, don’t give up,” says Murphy. “Because the first few years of his show were a disaster. Really a disaster. And then he told me how much luck plays a part in it.” His father once said to him that no matter how good his show might be, “If it’s raining, nobody’s gonna come.” Murphy links this to his disappointment in the sales of his first album: “No matter how good was my album Aquashow, if Polydor didn’t get it into the stores no one would be able to buy it.”

Murphy left college without a degree, and by 1971 ended up busking his way around Europe, during which time he also showed up at Cinecittà film studios, in Rome, at a casting call for a Fellini film. He landed a small role in Roma — handpicked by the director himself. “I was playing on the streets and doing that whole thing,” he recalls. “I missed the Summer of Love in San Francisco in ’67, but in Amsterdam, they were still kind of doing it.

“During that period in Europe, I started writing a lot of songs. Before that, I’d been mainly a guitar player. My heroes were Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, of course, and Jimmy Page. And I came back to America and very quickly got this band together, with my brother playing bass and some hometown boys from Garden City. And we made a demo, and we started shopping it in New York.”

Murphy and his brother knew someone who knew Paul Nelson, at that point a legendary critic who was then the A&R man at Mercury Records, so they made an appointment to see him. Nelson listened to their demos, and then and there decided to sign them. But days later, Murphy got an offer from Polydor that was twice the $5,000 advance Mercury had offered. Nelson advised them to go for it.

“Elliott got signed to Polydor by sending in a tape,” says Siegel during our video call. “I mean, you could do that then, and the AR man might actually listen to it. … He sent in a tape with no professional recommendation, no lawyer, no manager. And we liked it. So I think I arranged to hear them, and I believe I made a better tape in the studio, and that was the tape that I played for Polydor boss Jerry Schoenbaum and the tape I used as a producer as a reference for the songs.”

Siegel played banjo for the Even Dozen Jug Band, a group that also featured Maria Muldaur and John Sebastian, as well as Steve Katz. After that he joined Jac Holzman, the founder of Elektra Records, on his Nonesuch label, recording world music. But Siegel had originally called for Aquashow to be produced by Thomas Jefferson Kaye, who’d had a hit with Loudon Wainwright’s song Dead Skunk. Murphy recalled the first session in Los Angeles for Aquashow with Kaye: “We did a day in the studio. It was a disaster,” he says. “He wanted me to do, like, soft country rock. And I wanted to sound like the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan. Blonde on Blonde. So I kiboshed the whole session. I called up Polydor, I told them I’m coming home. And Peter Siegel, to his great credit, I think to save the project, he said, ‘Well, I’ll produce it myself then, because it’s gonna be hard to get another producer involved.’”

In Siegel’s recollection, it was Murphy who asked him to produce, after which Siegel assembled an exceptional group of musicians, including Gene Parsons from the Byrds and other top-notch session players, to create a sound that aligned with Murphy’s vision. The recordings were done in New York City, at the Record Plant, as “a night-time project,” as Siegel put it, since he had to show up for his day job at Polydor. But Siegel states that while he put together the musicians and “really produced it,” Murphy had everything he needed to make the gig run smoothly.

“First of all, he was a really good guitar player,” Siegel explains. “Which is really important to me as a record producer, because his electric guitar was what the band had to learn to hang on to. And so he was setting the rhythmic characteristics of the songs and actually all of these side musicians that I got were very capable of hooking into those rhythms, so that helps a lot.” That first album returned to the heartbreak of youth and the loss of his father, with the commemoration of naming it after his father’s business. In the cover photo, Murphy wears his father’s gold monogrammed cufflinks; his brother, with equally long blond hair, is visible in the background. The photo was taken at the Plaza Hotel, where a key scene was set in The Great Gatsby.

“Initially, his material, even more so than NYC — ‘White Middle Class Blues,’ ‘How’s the Family’ — I connected that personally more with Long Island, so it was rather interesting,” says Springsteen in the documentary. This was then new in rock music and reflected Murphy’s desire to be true to his roots, just as Billy Joel remained true to his own Long Island origins. “We went into the city to do our work, that was like our place where we did our job,” Joel says. “But we ran into some resistance early on: ‘Oh they’re from the suburbs, what do they know? Rich kids.’ A lot of people wanted to hide the fact that they were from Long Island, but Elliott didn’t, and I didn’t. We might have been the only two people who said, ‘No, we’re from Long Island. We’re from out of town. Sorry!’”

After the period of the major label albums ended, Murphy’s new career of producing his own independent albums began, starting with 1980’s Affairs and continuing up to today, with his 40th album, Wonder, released in late 2022 and updated with bonus tracks last year as Wonder-full.

Two future members of the Long Island Music and Entertainment Hall of Fame: Murphy with Lou Reed, in 1975. (ELLIOTT MURPHY COLLECTION)

Murphy was a precursor in self-published albums and books, all now released by Murphyland, although the books are also released by several other publishers around Europe. His most recent novel, Dorothy and the Discovery of America, is a collaboration with a Spanish writer, Peter Redwhite, and was published in Spain a year ago. When I ask Murphy if there was any connection to Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, he says, “Yes, but it was almost an unconscious link that I didn’t fully realize until we were well into writing the novel. Although it seems obvious to me now, I’m not sure if Christopher Columbus, upon ‘discovering’ the new world, remarked, ‘We’re not in Kansas anymore.…’” Murphy also has an ongoing series, The Tinnitus Journals (he suffers from the affliction), which is full of diary entries, photos, and other bits and pieces.

As we spoke more about life in France, Murphy got to the heart of why he feels at home there. He likes to quote Gertrude Stein: “America is my country and Paris is my hometown,” adding, “That’s the other thing about France, aside from the healthcare, aside from the intermittence du spectacle, there is a certain respect for culture. And what I do, rock ’n’ roll, is considered culture. In America, it is considered show business. And that’s a big difference here. You are in the world of culture if you’re a chanteur compositeur, if you are a singer-songwriter. And for them, you’re in the same line as [singer-songwriter/poet] George Brassens, all those people.” And, of course, the singer-songwriter most often spoken of in the same breath as Brassens is Brel.

This brought us back to the ever-changing landscape of the music business, and how the collaboration between music and other industries, such as fashion and film, has reshaped the business model. “There’s more music than ever,” Murphy says. “When I started, there was no rock music in films, there was no popular music in commercials on TV. Now it’s everywhere. There was absolutely no alliance between fashion brands and music, and now that’s a major part of the music business.

“When my first album was not selling so well on Polydor, I said, ‘You know, you should make a special edition and put it in a Louis Vuitton cover and sell them for $1,000 a piece.’ And they said, ‘But, Elliott, you can’t … rock ’n’ roll is not supposed to be about luxury brands.’ That’s completely changed.”

Then Murphy summed up the heart of the matter: “As long as there is that emotional connection that music has, it will keep going.” When I respond that I thought the music business today was no longer about the business of albums or singles but about live performance, whether by well-known bands or beginners, he concurs, saying, “That is the most authentic moment. And when you make that connection — look, I do it at the New Morning every year for 30 years, that’s when it becomes the most real. It used to be the most real … I remember the first time I heard ‘Last of the Rock Stars,’ off Aquashow, on a radio station in New York. That’s when it was: ‘This is really happening!’

“For me, though, music was always a vehicle to tell my story,” he adds. “Today, hit records have five, seven writers on them, so they are not telling anybody’s story. They’re just trying to capture an emotion that the public will relate to. And that’s valid. I have nothing against it. But where I came from, and I’m talking about from the Beatles to the Stones to Bob Dylan to the Kinks, me to Bruce, we all told our own stories somewhere in there. Look at all the Beatles classic songs, all those references: ‘Penny Lane.’ Sergeant Pepper was a poster that they saw somewhere. It wasn’t just seven people getting in a room and saying, ‘Well this was a hit last week.…’” Murphy’s words underscore the distinction between music that is timeless and music that is fleeting, mirroring the disposable nature of fast fashion, which he believes is what’s behind the big buyouts of artists’ catalogs, like the multi-million dollar deals made in recent years for the Beatles, Springsteen, and Dylan.

“I don’t think they are going to make those deals for the current artists,” he says. “Because I don’t think it has the same lasting power. It doesn’t mean it’s not good, or it doesn’t work. It’s because it’s based on the money. It’s very disposable. We’re in the era of fast fashion, Zara and everything else, it’s very disposable. And it’s the same for music.”

Murphy’s own prolific output is impressive. When I ask how he managed to consistently release new albums every year, he says that perhaps it was because he was “so lazy,” since artists often had too much time on their hands, leading to trouble with vices like booze and drugs. “If you can’t come up with 10 good songs a year, then what are you doing here?” he asks. “To me, it’s not difficult, that’s my job. It should also get easier the longer you do it. I mean Picasso used to whip out those paintings.”

Then he adds: “Here’s the cycle: You pick up the guitar, there are songs in that guitar, you write those songs. Once you write the songs, I want to record those songs. Once I record those songs, I want to play them for an audience. And then the more you play live, the more you pick up a guitar at home or in your hotel room, you start writing songs and the cycle starts again. So for me, the live part of it is kind of the engine that keeps it going. I wrote a lot less songs when Covid was here.”

As our conversation drew to a close, I asked Murphy if there was anything in particular he’d like to share, a message or insight. He paused for a moment. “I think what I would say is, ‘Where am I at now?’ I’m 74, I just released around my 40th album. I’ve never really had a huge international hit. Although my son assures me that just a career for 50 years is a hit in itself. I’ll go with that.” Then he adds that writing his memoir made him realize something else about his own life. “I’m sure I’m like everybody on the planet,” he says. “When you’re living your life, it’s chaos. You’re just making the best decisions you can based upon the information you have and just hoping you don’t fuck up too bad. And yet, when I wrote my memoir and I looked back, it all looked like some perfectly conceived plan.

“Like, of course I was going to end up in Paris, of course I was going to keep playing at the New Morning, of course I was going to … so wherever I’m at, and wherever I am, here, at this point of my career, I think I’ve accepted it as my destiny. And that is a very relaxing place to be. It’s a good place to be. I’ve stopped fighting, saying, ‘Maybe if I would have done this, this would have been more successful, if I would’ve done that, that would have happened.’”

Then Murphy hearkens back to my thoughts, and Springsteen’s response in the documentary, about his making the choices he did about his career because that’s the way he preferred to live. “I’m at a really comfortable level of celebrity. Because I know people who are so famous, they lose their anonymity. And that is a big loss, when you can’t go out on the street anymore. But when I go out on the street, if I get recognized it’s usually a very pleasant moment: Someone says, ‘Oh, I love your music.’ And if it’s a beautiful young girl, she always says, ‘My father really loves your music.’ That’s changed.”

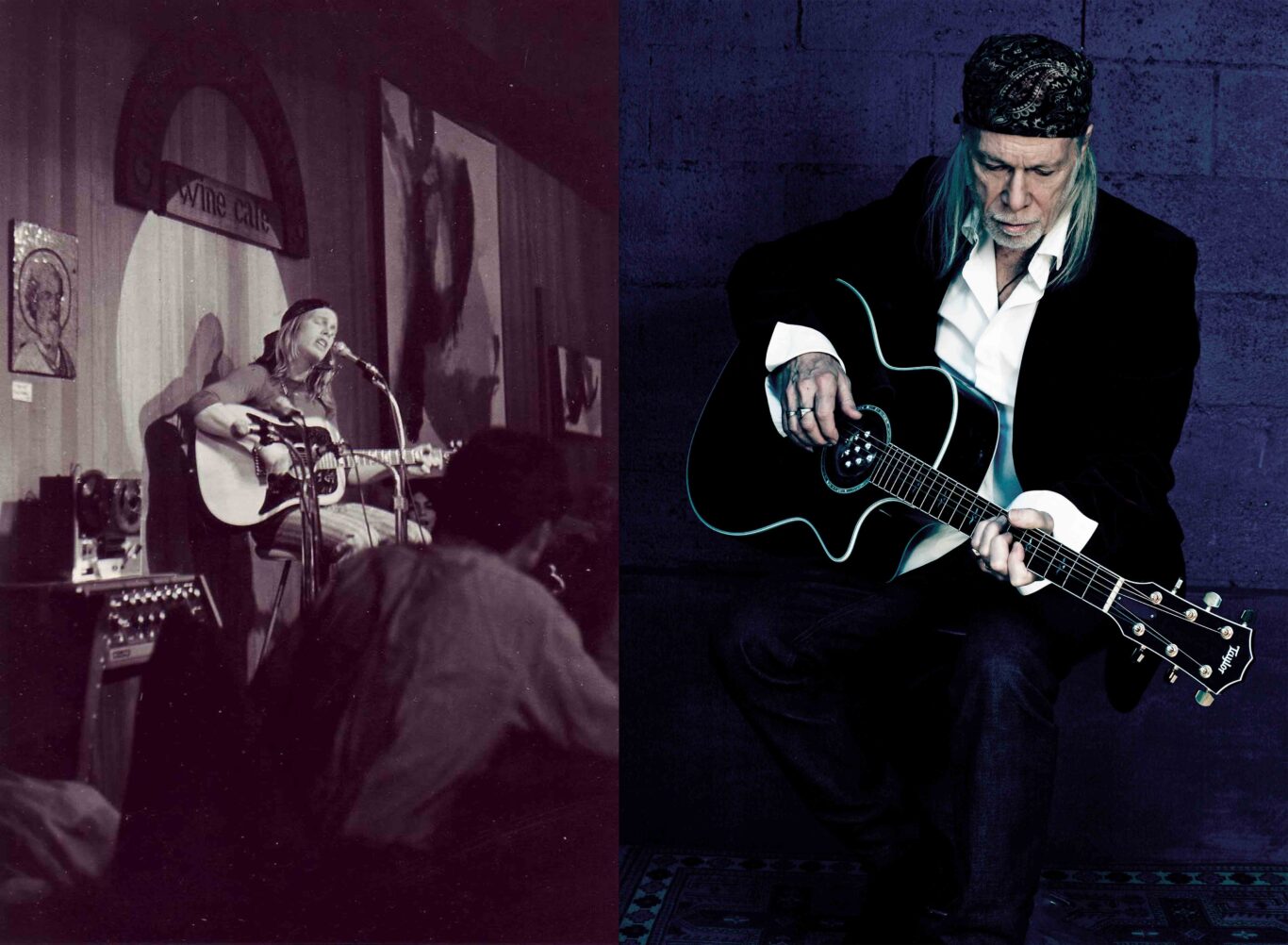

Murphy in San Francisco in 1972, and in Paris today. (L: ELLIOTT MURPHY COLLECTION / R: PHOTO BY MURIEL DELEPONT)

But when asked if he did not still hope somewhere, somehow, for that international hit that has eluded him, Murphy answers, “I think what’s kept me going all these years is the hunger. You still have to have a little of that. The hunger for that thing and every time you put out an album, you think, ‘This is the one. For some reason, some miracle is going to happen, and everyone can see it and hear and recognize it.’

“But I’m very fortunate really, thanks to France — and Europe in general — that I did find this niche that I have here. I like living here, I like the European lifestyle, so I’ve been able to take advantage of it. And I’ve been successful enough to keep going. But I’m still hungry at 74. I’m not sure for what, but I’m still hungry.”

—

Brad Spurgeon is a journalist and musician based in Paris since 1983, where he was on staff at the International Herald Tribune for 33 years. His latest book is Formula 1: The Impossible Collection, and he has recently completed a 21-part documentary series about musical open mics worldwide.

Editor’s note: The disclaimer below refers to advertising posts and does not apply to this or any other editorial stories. LA Weekly editorial does not and will not sell content.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.