Los Angeles is no stranger to the recent crime wave targeting California’s booming cannabis industry.

It’s now commonly known that the neighborhoods around cannabis dispensaries tend to be safer than their counterparts due to features like security guards, surveillance, and good lighting. But a recent wave of crime across the state is proving the giant piles of cash that bankless retailers are forced to hold on to are luring criminals looking for a quick big score.

The year has seen numerous robberies in The Emerald Triangle, Sacramento, Oakland, Los Angeles, and all points in between. These have included stick-up kids getting away with 20 pounds of flower with a retail value of $156,000 and the cracking of a safe by someone a bit more technically adept in a separate incident. That latter effort was said to score $161,000 destined to be taxes. Sacramento industry insiders say two places were hit in the same night.

“Last year a delivery service in Sac was robbed of $250k worth of product. When they called police and it was on a weekend, they sent out a volunteer to take fingerprints,” said Jacqueline McGowan, founder of 8,000-strong California — City & County Regulation Watch Facebook group. “They didn’t care that the company had video of the robbers including pictures of their cars and license plates. Would a jewelry store owner have been told that detectives don’t work on weekends?”

Sacramento is also home to the California Bureau of Cannabis Control. We reached out to the state to ask if they keep an eye on how the policies being developed in Sacramento are impacting public safety across the state; the BCC told L.A. Weekly they do not compile that data.

An L.A. Problem Too

Moving closer to home, we asked the Los Angeles Department of Cannabis Regulation if they’d been monitoring the situation. While they weren’t, there was a quick handoff to the Los Angeles Police Department and we started getting answers pretty quick.

The LAPD reviews from local operators have gone a bit better than for some of their peers up north. “LAPD is always very cool if we have an issue. Matter of fact check out this pic of them in our lobby when the alarm went off. I’d say we are well protected!,” said Buds & Roses president Aaron Justis. “They caught the burglars. They didn’t catch them in the act but with our footage and other dispensaries footage, they identified the guy.”

Caught on Video — Three suspects forced their way into a marijuana dispensary at a strip mall on PCH in Harbor City. Their getaway car was a possible Jaguar with tinted windows & chrome rims. Any info contact LAPD Harbor Burglary Detectives 310-726-7850 https://t.co/JiBEpCeZ1H pic.twitter.com/C4imWBtQU6

— LAPD HQ (@LAPDHQ) August 16, 2018

While the analyst supporting the LAPD Gang and Narcotics Division Cannabis Support Unit wasn’t available to give the exact breakdown of crime in L.A. between licensed and unlicensed operators, Detective Vito Ceccia told L.A. Weekly his “well-educated” guess was the lion’s share of robberies are happening at unlicensed locations. The police end up there on calls despite the obvious consequences of them coming in and realizing the lack of a permit.

Buds and Roses

Ceccia provided the Year to Date L.A. Crime Stats for all crimes at cannabis facilities, regardless of their legality, as of September 4, 2019. The LAPD has tracked 20 robberies, 30 aggravated assaults, 3 burglary/theft from motor vehicle crimes, 15 theft-related crimes, and 57 burglaries. This totals out to about 77 property crimes and 50 violent crimes.

Those numbers also top last year’s. The total number of crimes by late September 2018 was 105, according to the data the LAPD provided Crosstown. 70 of those crimes happened in a retail or medical dispensary.

Then on top of all those numbers are the many crimes that go unreported.

For the most part, the officers are familiar with their divisions. They already know who is operating without a license according to Ceccia. Regardless of the legality of a dispensary operation, if there is any kind of crime it’s put on LAPD’s radar locally within the division.

We asked what LAPD is doing to get licensed operators ahead of the curve in protecting their operations. Ceccia says while the licensed operators do fall victim to crime, “they’re more diligent about how they control their money.”

When asked about general banking issues in the industry leading to tempting piles of cash for would-be robbers, Ceccia said alternatively from beliefs by many industry advocates he thinks licensed operators are depositing their money regularly, much of the time with armed transport.

“It’s not someone with a duffel bag throwing it in the trunk just bringing it to a house or other location,” Ceccia said. “The city is allowing [operators] to pay their taxes with that cash, so obviously some of the money is going to that.”

Ceccia says the lack of security measures at unlicensed locations make them a bigger target and more likely to be a victim than those who have jumped through the hoops of the permitting process. “But when you say both of them are victims of robberies, absolutely,” Ceccia said, “When the robbery occurs it’s usually for the product, the money, or both.”

We asked Ceccia if it was difficult to work with legacy operators that have been traditionally wary of cooperation with law enforcement given the decades they spent in California’s black, then grey, market to what we have now.

“From my perspective, being a plain-clothed investigator that has been doing police work for almost 25 years, I haven’t received or heard about that much resistance or anxiety when I go into one of these locations,” Ceccia replied. He says most of them are good partners to the city, law enforcement, their communities, and “as far as I can tell transparent in their operations because they’re doing everything they’re supposed to be doing.”

Ceccia went on to note on the transition of the times.

“You gotta understand, when you get a police officer that’s more than five years on the job, it’s like a cultural punch in the gut. You gotta understand for someone like myself doing this for 25 years; sales, transportation, possession for sales was always a felony. It was always a good felony. ”

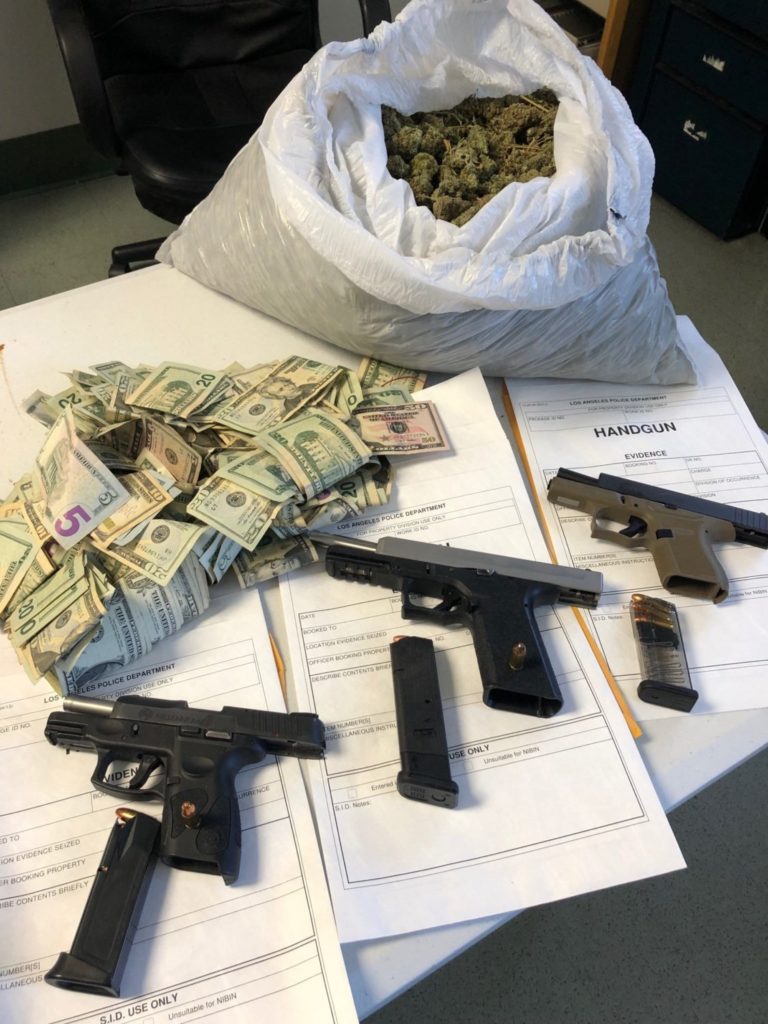

(Courtesy of LAPD)

Ceccia claimed officers spent most of their time going after people with the intent to distribute. “Now you tell someone who has been working narcotics the last 10, 15, 20 years. ‘Hey this is no longer a felony’ and someone who has been working patrol that this is no longer a felony, initially it’s hard to wrap your head around.”

Ceccia says legacy operators have to understand certain members of the police department have to go through an acclimation period. “Where they get used to it.”

Ceccia says now it’s similar to a lot of the codes they enforce around alcohol and tobacco.

“As new officers come on and the mindset changes, that apprehension is going to go away. But I think on both sides of the fence there’s that apprehension. Some people in law enforcement may not fully accept the current state of affairs. Then you have legacy operators who at one time may have been operating in the shadows and now they’ve done everything they’re supposed to do, they have a license, but they’re still leery anytime a black-and-white pulls up near their store.”

Ceccia believes part of the stress on local operators is due to federal regulations. He thinks despite President Donald Trump and his Department of Justice reaffirming they won’t be going after state-legal operators, things could change in an instant at the federal level. Ceccia says he gets that concern is part of the problem. “I mean you just never know. If I were one of those legacy operators I’d be more fearful of that happening than local law enforcement.”

The Dual Advocate

Dale Schafer has watched the evolution of marijuana in California from both sides of the fence. Both as a lawyer representing members of the law enforcement community, and as a medical marijuana activist hit with a five-year mandatory minimum prison sentence alongside his wife and fellow activist Dr. Marion “Mollie” Fry. They were released in late 2015 and Schafer immediately got back into the industry.

“I’ve been inside law enforcement politics. I used to represent cops. I still have connections to law enforcement, old friends. We still talk about issues in law enforcement. So I have that perspective, then I went through the colon of the criminal justice system and spent some time in prison. So I’ve looked at it from that angle,” Schafer told L.A. Weekly in a phone interview.

Schafer says he has seen the best kind of cooperation take place when it comes to the cannabis industry and cops, but has also seen “knucklehead tribalism.”

“The coordination is not always what we may want to see on the enforcement side,” Schafer said, “There are obviously some people out there we need to figure out how to grab. So the issue of law enforcement resources being used for crimes in this industry is not one where you’re going to find a lot of support in law enforcement.”

Schafer family (Courtesy of Heather Schafer)

Schafer believes a lot of people just “check off the box” with their security plans. The expert Schafer works with on security plans is a former cop. “He’s been frustrated. He’s written security plans from the perspective of ‘I want to protect your business from criminals I know are coming’ and businesses don’t want to invest or maybe don’t have the money to invest in that deeper level of security.”

But when someone comes in and steals cash and/or a $100,000 or more in product operators outlooks on preparations change.

“There is a ton of money from the industry going to the coffers of different jurisdictions, and one would expect we have at least the attention of law enforcement to put some resources toward the industry,” Schafer said, “But that’s not how the politics are working on the cop side.”

Since a decent amount of the money coming in is going directly to law enforcement, we asked Schafer what it would take to get less supportive agencies to be more protective of their own new revenue stream? Or does it simply not balance out to how much was being raked in under full-court press prohibition? Is there an incentive to protect these businesses?

“The short answer is no,” Schafer replied, “Inside the politics of law enforcement there is a feeling that the stoners won. It’s hard to get anyone to put it into those kind of words, but the war on drugs was a moneymaker for law enforcement.”

Schafer didn’t want to use the word gravy train, but if you were cooperating with federal and state policy targeting cannabis and other drugs when enforcement really geared up you got money in your coffers. “Prop. 64 pulled the rug out from under enforcement and justification for resources to go after marijuana,” he said.

Inside law enforcement special interests groups the conversation has changed to how are they going to move on from this transition in enforcement paradigms? “Who’s getting paid? Do I get a chance if I’m just writing up misdemeanor cultivation cases?”

“Cops get points for the things they do, it’s kind of like the military. They like you to tell us they went out and got bodies,” Schafer said, “Well, misdemeanor bodies aren’t going to get you as far as felony bodies. It’s not simple, but there are a lot of pieces to this. And on the law enforcement side, they watched after SB 420. The industry started spraying starter fluid and just took off.”

Schafer said from law enforcement’s perspective it was out of control, “cops got their asses kicked a number of times so they didn’t quite know what to do with enforcement.” This led to paths like zoning enforcement, “then we eventually got regulations the state would soft enforce through fines and revocations.”

After all this, Schafer said it’s important for businesses to understand they have to protect themselves first. If they rely on law enforcement, depending on the willingness of the agency, they could be let down.

Schafer says as legalization has rolled out from the bigger cities to smaller rural areas, gangs have figured out how to target the industry. Schafer doesn’t know how or why but suspects it’s simple because how accessible the operators’ security plans are to the public or any of the various places involved in the vetting process.

“As with anything, employees will waggle their tongues for money. Inside information can get out. These businesses are being hit in ways that would make someone in law enforcement or security think these people are investigating and perhaps gaining information from employees. They got a plan, they’re going to be able to come in and hit you, and law enforcement isn’t going to be able to stop that unless they really track people down and put resources in. And then we’re back to who is going to do this?” said Schafer with a laugh.

We asked Schafer if the giant piles of cash sitting around to pay taxes played a role in the motivations of criminals. “That’s hard to know,” he replied. He spoke on a client in Sacramento that had recently been robbed. “They got hit and I don’t think they were lax in security or anything like that, but banking is a terrible problem.”

Schafer next weighed in on if regulators at the state and local level are doing anything to push operators to secure their cash? He said no, “right now the state is more reactionary.”

“They still haven’t onboarded enough employees to carry out the programs they’re mandated to carry out,” Schafer said, “The state, almost by its nature, is not doing enough. If there really was liaisons and cooperation between the state, operators, and law enforcement for this kind of activity there would be alerts out. There would be notifications out. There would be hyper-alertness that, ‘hey someone in your area got hit. Be on alert.’ That’s left up to operators in competition with each other to let somebody else know. And I don’t think that’s a long term sustainable situation.”

Federal Solutions

One of the fastest solutions to not allowing criminals to get their hands on the giant piles of cash is for them not to exist in the first place. The National Cannabis Industry Association weighed in on how things are going on Capitol Hill in regards to banking access.

“This is first and foremost an issue of lack of access to banking and financial services,” NCIA Media Relations Director Morgan Fox told L.A. Weekly. “No other businesses apart from banks themselves are forced to keep large amounts of cash on hand and make themselves targets, and cannabis businesses should not be forced to protect themselves like banks just to be able to operate normally. Hopefully Congress will address this issue and move to pass the SAFE Banking Act when they return to DC next week.”

Fox said the heavy financial burdens placed on cannabis businesses at the local, state, and federal level also plays a role.

“High tax rates are forcing businesses to keep way more cash on hand than they would normally need to, and it is certainly contributing to making them targets for crime. But it is not just taxes,” Fox said, “No banking means they have to keep payroll and all other expenses on hand, as well as reserves to cover unexpected costs. It is an untenable situation, but one which can be easily rectified by lawmakers.”

The nation’s oldest marijuana reform organization has also been pushing the issue of banking access and its relationship to public safety as well. NORML testified to the United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs last month on the subject.

NORML’s California-based Deputy Director Paul Armentano told L.A. Weekly federal lawmakers are mandating that this rapidly growing multi-billion dollar industry operate on a cash-only basis in “an environment that makes businesses more susceptible to theft and more difficult to audit.”

Armentano went on to note the current status of banking and associated lack of merchant services also places the safety and welfare of these businesses’ customers at risk, “as they must carry significant amounts of cash on their persons in order to make legal purchases at retail facilities. Similarly, it needlessly jeopardizes the safety of retail staffers, who are susceptible to robbery.”

“No industry can operate safely, transparently, or effectively without access to banks or other financial institutions and it is self-evident that this industry, and those consumers that are served by it, will remain severely hampered without better access to credit and financing,” Armentano said, “Ultimately, Congress must amend federal policy so that these growing numbers of state-compliant businesses, and those millions of Americans who patronize them, are no longer subject to policies that needlessly place them in harm’s way.”

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.