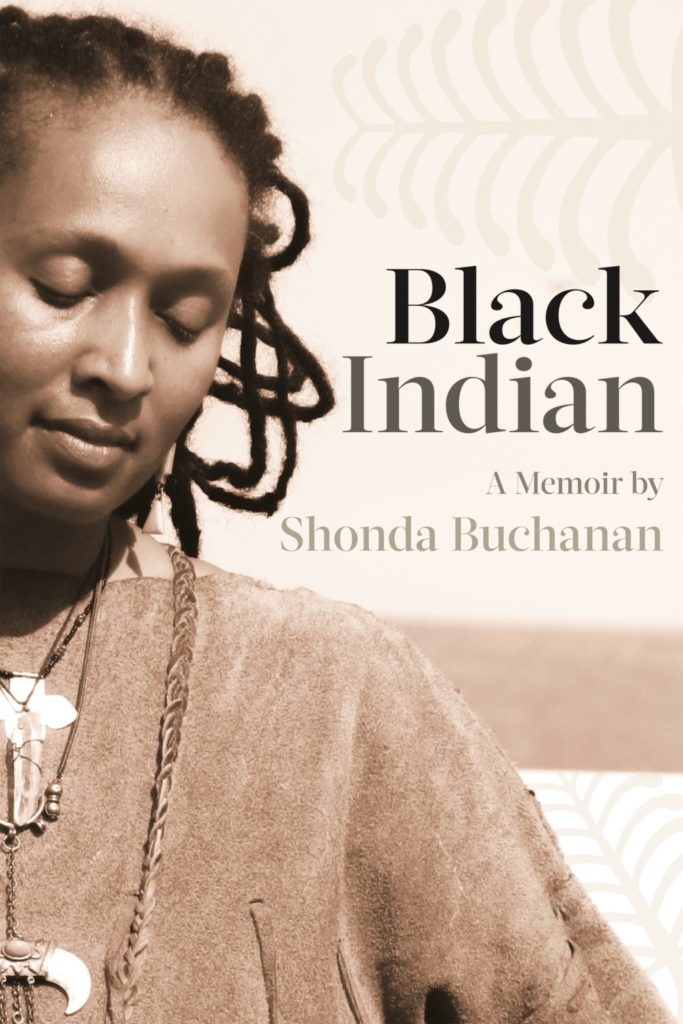

“I think my mother could see in my wet eyes when I was born that I didn’t know how to keep my mouth, the way she would say it — I often felt like my stomach was on fire if I didn’t say the thing burning in my mouth,” Shonda Buchanan writes in her compelling new memoir, Black Indian (Wayne State University Press).

The Los Angeles poet, teacher and L.A. Weekly contributor refuses to “keep her mouth” as she uncovers her family’s complicated history — a fascinating and often-shocking story of madness, racism, genocide, perseverance, love and loyalty that mirrors the secret history of the United States — even as her sleuthing and multigenerational soul searching angers many of her relatives.

“This is not a scholarly book. It is a story, and I do not mean to offend anyone with it,” Buchanan declares at the outset, in the author’s note. But the writer’s metaphorical vision quest to discover her true identity as a child of multiracial parents — African-American, Native American and European-American — while sifting through the wreckage and contradictions of her family’s tragic past, parallels this nation’s ongoing evolution to reconcile its democratic ideals with the realities of slavery, poverty and racism.

“It was years before I realized that I was not only attempting to follow my own family’s breadcrumbs, I was tracing the kith, creed, and ethnicity, and very origin of the beast — the ugly history of racial formation in this country,” she writes. Although Black Indian is indeed not a staid, scholarly account, Buchanan nonetheless spent years digging for clues about her ancestors’ lost and sometimes willfully forgotten lives — a search that inevitably reveals the pervasive impact of crucial events and government policies that are often left out of most history books.

And yet, even as Buchanan boldly confronts and acknowledges the monumental forces and conflicts that continue to shape — and divide — this country today, she is ultimately telling a richly engrossing story that is distinctly specific and personal as she reveals her bittersweet love and loathing for her own family. It helps that her family members are so individually intriguing, and not just in how they relate to one another but also in how they choose to deal with their own issues of identity across a wide physical and internal landscape spanning several centuries.

In the beginning of the book, Buchanan sets herself up as an outsider in her own family, a perspective that helps her remain somewhat stoic and objective until she can’t help being swept up in some of the same passions, insanity and violence that have, at times, driven her family apart. Born and raised in Kalamazoo and the nearby rural village of Mattawan, the author thinks she has left her family’s messy past far behind her by relocating to her longtime home in Southern California. But Buchanan reluctantly returns to Kalamazoo to attend the funeral of her Aunt Phyllis, an event that stirs up intense dread even as it launches her journey of self-discovery.

“My family reunion looks like death, deep in the night sky,” she writes. “A shroud of swamp moss holding the moon’s hair together. Indian ghosts and weeping willows borrowing our silence for their children’s bones. … They grow. We grow. We return to them, forever bound together.” The memoir is enriched by Buchanan’s poetic acuity and febrile imagery, which elevate her story beyond prosaic storytelling into something far more profound and enduring. The writer previously touched on themes of racial identity in her artful poetry collections Equipoise: Poems From Goddess Country (2017) and especially Who’s Afraid of Black Indians? (2012), but she plunges much deeper into the mystic with Black Indian.

Buchanan’s difficult relationship with her mother, Velma Jean, is at the center of the book. At first, Velma comes off like a monster, lacerating her mourning relatives with needlessly cruel words and actions that make her appear irredeemably heartless. Later, as Buchanan finds out more about the violence and abuse her mother suffered at the hands of her lovers — as well as being raped by a sister’s husband — Velma turns out to be a more complicated person. By the end of the book, Buchanan can’t help relating to and identifying with her mom, one of several strong women in her family who have been crushed by sexism and institutionalized racism.

“It seems as if her childhood had never happened. As if my grandfather’s tight-axe grip is still choking her all the way from the grave,” Buchanan writes. “The gaps in her memory make it seem as if she’d skipped her own childhood. But I’ve persisted, refusing to believe that my mother’s memories have sealed themselves up like two swollen eyelids after a fight, protecting the eye from what it couldn’t see — the next punch.”

At the funeral, Buchanan’s heart melts, and she considers saying something to comfort her mom, to connect with her emotionally and break down the invisible wall of silence that looms between them. Instead, the daughter says nothing. “My tongue is a thick book in my mouth,” Buchanan confides. “If I opened it, the words I want to tuck in her ears would simply scatter like pages in the wind before I could identify which ones I want to catch and show her.”

Shonda Buchanan (Tracy Roberts)

The problem isn’t just that Buchanan and her relatives have suffered from prejudice as African Americans and Native Americans. The writer delves into the myriad ways that oppressed people sometimes turn on one another. African-Americans often don’t see Buchanan as one of them because her skin is lighter and her hair is straighter. Some Native Americans view her with suspicion because she has black and white blood. And even some people of mixed heritages judge her on the basis of how light her skin is. Native people are further divided because some have historical documentation that allows them to acquire all-important tribal-enrollment cards — which confer on them a sense of identity and place — while others are caught in a kind of limbo in which they are viewed with suspicion by full-blooded Indians.

Buchanan sagely points out that the real enemy is the white governmental entities that have historically and purposely employed such divide-and-conquer techniques and ruses to keep people of color powerless and confused. “We didn’t know any history; we didn’t know our history,” she states. “That was the Problem.”

Later, she adds, “And yes, because of racism, prejudice, and discrimination, a sense of privilege came with passing or claiming Indian blood, but only after American Indians had been defeated across the country. Before that, being one was dangerous. But we were not ‘claiming’ it. Our records said so. Our DNA says so. And we were dangerous. … Our Blackness and our Indianness, not our whiteness, were undeniable in our bloodline and our faces, on my face; our blood was at war.”

It only makes the writer more determined to doggedly research the truth about her family history, a process that simultaneously empowers her and overwhelms her when she realizes how the women in her family, in particular, have struggled to maintain a sense of dignity while battling forces even more consuming and life-altering than drunken, defeated, abusive husbands.

“There is an oppressive silence hovering over us,” Buchanan says. “A desire to be gone, to disappear into this silence that we keep locked up and protected. We look at each other, but we don’t see ourselves. We never name the depression that links us, leaving us ravaged in places language cannot name.” Relieving herself of “this burden of memory,” the dutiful daughter finally opens up to her mother about her feelings, even as she realizes, “You can’t pick and choose your memories; your memories choose you.”

The one thing that does make sense to Buchanan is writing and documenting all the history that has been buried, either by social forces or personal shame. It is how she finds herself. “I see history as a lesson with teeth,” she writes. “We are the pages ripped out of history books. … We remain a racial invention on a sheet of paper; we checked on a box on the census that represents only half of what we are. Not the whole. Colored or white.”

She laments about the deception inherent in census polls and government classifications of multiracial identities, and how Native Americans still quarrel over who should be allowed to have a tribal-enrollment card: “Cousins, aunts, uncles, sisters, and brothers fighting for scraps at the federal government dinner table. Fighting each other for the right to be counted the real American Indian. To remain Indian.”

Buchanan feels just as disconnected in the African-American community. “We didn’t look Africa Black. Our skin tone incriminated us. Our high cheekbones and our soft, spongy hair set us apart.” With many of her family’s records lost or destroyed, she has to search far and wide to learn about her ancestors. “I was a cartography lesson. I was the geography of the intersection of enslaved Africans, Eastern Shore American Indians, indentured white servants; their journey was on my face. I was the seed of a memory that my grandparents wanted to forget.”

The author battles to rediscover her own history and struggles against the ongoing social forces that have kept minorities powerless by stripping them of their identities, their histories, and even their original names and languages. “This was the social legacy of erasure. … This could have been why my men were so hogtied angry; why my women kept goddamn quiet. Come hell or high water, we stuck together,” Buchanan muses.

It is the women that keep her family together, despite suffering the betrayals of men who cheat on them or abuse them. “Anyone looking for bruises will find none: They are all under the skin,” Buchanan writes. Her heart breaks when she thinks of the violent man who broke into her mother’s house: “I didn’t start crying right away, not until I saw my mother’s face fold inward like a trampled bud.”

Buchanan sees how abuse and self-hatred become intertwined over generations, especially after she encounters a molester. She evolves from hating her mother to grudgingly respecting how difficult it was for mom and her aunts. “Despite everything, I recognize, and to an extent even admire, the steadfastness next to the misery, knowing that for my mother and her sisters, there had to be love somewhere in the beginning. Something shared and good before the bad times. But theirs was not the intimate love of seasons changing but the obligatory love of soldiers, an acceptance of the pallor of war. I know I could never be that brave.”

Instead of protecting them, love is often the mechanism that has destroyed these women’s lives. “No matter what age or generation, that heart, the strongest muscle in our body, ruins our capacity to run, to fill our air with lungs and just lunge out of the way of a coming train, of a failing marriage, of an absurd life, of self-destruction.”

And yet there is a saving grace in the lives of Buchanan and her women relatives. Many of them have dreams that tell the future, that help guide them away from oncoming shipwrecks. It is through this alchemical magic that Buchanan is able to both reinvent herself and connect with the family she thought she had left behind. “We were living a dramatic play, each moment of our lives an example of hard-won battles, of the glory and the tragedy of growing up in a large family in the Shakespearean Midwest,” she writes.

As a young child cleaning and dusting her mother’s furniture, Buchanan realizes that she possesses the gift of making words sing. “This was, I know now, my first taste of poetry, as I struggled to describe that scene and the dust that spiraled in and out of the sun beams, stealing through the window above me.” In dealing with the aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and the subsequent breakup of her parents, Buchanan receives — and gives back — the gift of insight: “Maybe because of all this loss, this losing of kings and fathers, maybe that’s why I like to know the sad parts first.”

Shonda Buchanan discusses Black Indian in a conversation with Asha Grant at the Umoja Center, 3347 W. 43rd St., Leimert Park; Wed., Sept. 11, 6 p.m. Later that evening, she reads at the World Stage, 4321 Degnan Blvd., Leimert Park; Wed., Sept. 11, 8:30 p.m. And she reads at the Autry Museum, 4700 Western Heritage Way, Griffith Park; Sun., Sept. 22, 2 p.m. (323) 667-2000.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.