Who would’ve thought that one of the best rock documentaries in recent memory would be about someone who lived on the periphery of the tempest rather than inside the storm itself? Perhaps the view of the circus that was the Rolling Stones during the ’60s and ’70s is more authentic when seen from the margins and not center stage. At least that’s how it felt watching Catching Fire: The Anita Pallenberg Story, a potent, delicately rendered portrait of the famed model and actress who found herself twisting in the eye of a rock and roll hurricane.

Who would’ve thought that one of the best rock documentaries in recent memory would be about someone who lived on the periphery of the tempest rather than inside the storm itself? Perhaps the view of the circus that was the Rolling Stones during the ’60s and ’70s is more authentic when seen from the margins and not center stage. At least that’s how it felt watching Catching Fire: The Anita Pallenberg Story, a potent, delicately rendered portrait of the famed model and actress who found herself twisting in the eye of a rock and roll hurricane.

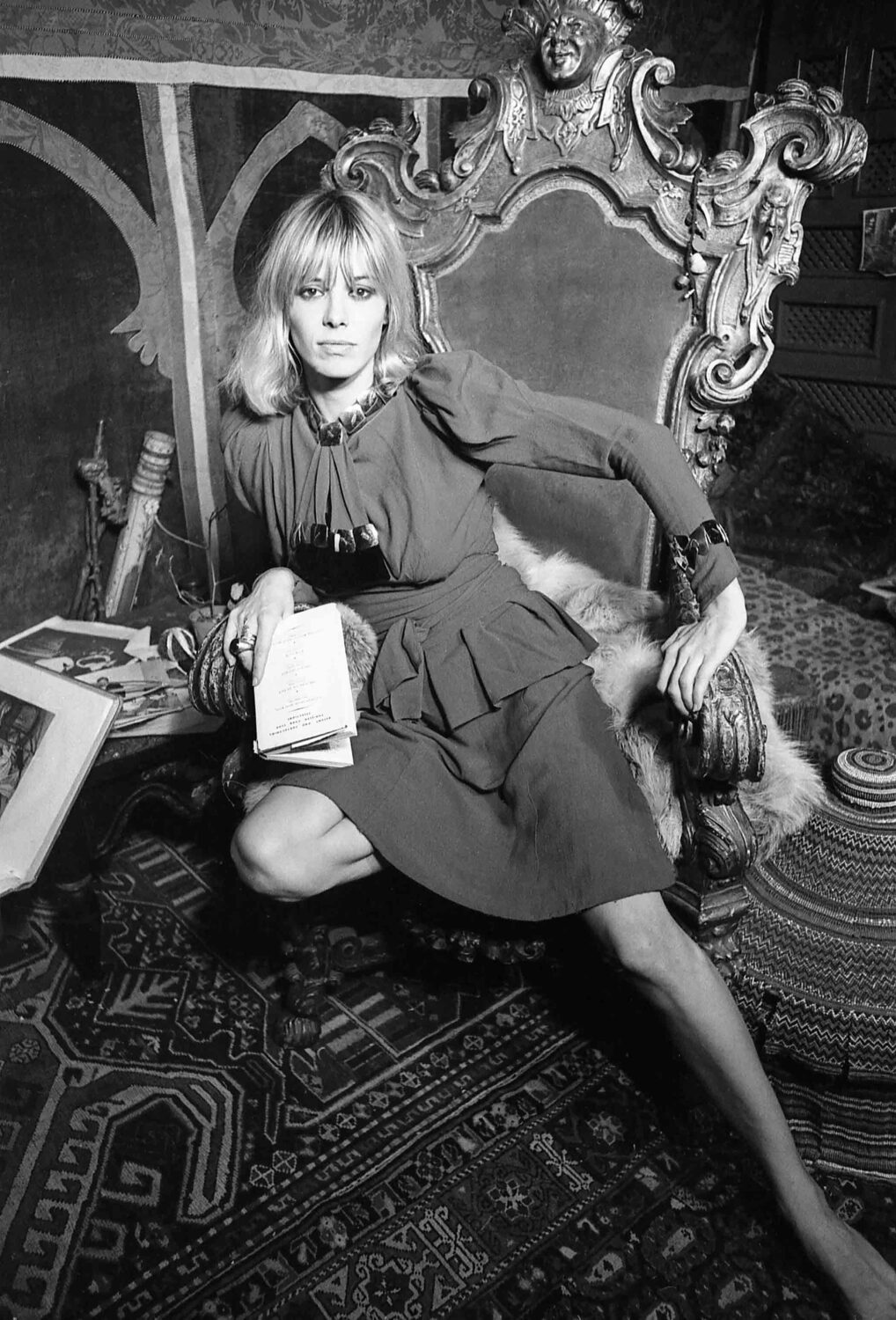

The ultimate “It Girl” of the ’60s, Pallenberg was a stunning European model who created friction for the Rolling Stones when she left founder and multi-instrumentalist Brian Jones for guitarist Keith Richards. She is also considered the penultimate “rock wife,” whose relationship with Richards lasted longer than anyone could’ve predicted. But as this film convincingly contends, Pallenberg was more than an annotation in the band’s bio or a muse to the band’s principal songwriters. She was also a highly intelligent force of nature who starred in some of the best avant-garde films of the era and became an important fashion icon. Her sense of style still inspires the industry today; Kate Moss is interviewed in the film.

Directed by Alexis Bloom and Svetlana Zill with a craftsmanship that’s equally loose and deceptively refined, the film is narrated by actress Scarlett Johansson, who reads excerpts of Pallenberg’s unpublished memoir. Johansson lends Pallenberg’s unsentimental words a spectral poeticism that floats through the film like a sparkling cloud. “I’ve been called a witch, a slut, and a murderer,” Johansson reads in the opening voiceover, as we watch a striking blonde twirling in a cape, floppy hat, and pair of go-go boots.

Born of German parents on April 6, 1942, in Rome (or perhaps Hamburg, Germany, according to her son Marlon), Pallenberg was sent to live with family in Germany while the war was raging. “My earliest memories are hearing airplanes dropping bombs,” Johansson reads from Pallenberg’s memoir. Later in the film, Richards admits they were probably drawn to each other because they were both “war babies.” A descendant of an artistic but orthodox family, Pallenberg rebelled by dropping out of high school in Germany and traveling to New York (“In New York, I hardly spoke any English, but I had an awakening”). There she quickly ascended from assisting artists in their studios to commercial modeling and hanging out with Andy Warhol’s Factory crowd. As her friends attest, Pallenberg’s zest for life was like a beacon of light for everyone in her circle.

Modeling sent Pallenberg all over the world and also back to Germany, where she saw the Rolling Stones in Munich, in 1965, and met Brian Jones backstage. The two fell in love and became a popular couple, resembling twins with their blond locks and Swinging London glamour. Soon, however, Jones’s drug use and erratic behavior progressed to physical abuse, forcing Pallenberg to seek refuge with Richards. Richards was happy to help, confessing in a new audio interview for the doc that he was “bursting in love.” As Richards and Pallenberg consummated their relationship, Jones descended into a druggy haze that eventually led to his death, at age 27 in his swimming pool, in 1969.

Meanwhile, budding filmmakers were drawn to Pallenberg’s stylish verve and plucky humor. She was cast in a succession of movies, including the German film Degree of Murder (1967) and Roger Vadim’s Barbarella (1968), in which she played “The Great Tyrant” opposite a nascent Jane Fonda. But it was Nicolas Roeg’s Performance, which also starred Mick Jagger, that allowed Pallenberg to stretch her acting muscles. According to excerpts from her memoir, she had an affair with Jagger during the making of Performance simply because they spent so much time together. Jagger’s girlfriend at the time, Marianne Faithfull, who was interviewed for the film, recalls that she and Richards knew something was going on. According to the memoir, Richards spiraled into a deep depression because of the affair but “never spoke about it, he just stayed silent.” After wrapping Performance, Pallenberg went back to Richards and began rejecting Jagger’s advances; she says this is around the time that a heartbroken Jagger penned “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” However directly Pallenberg influenced that Stones hit, Richards maintains in the doc, “Anita is in a lot of those songs, absolutely.”

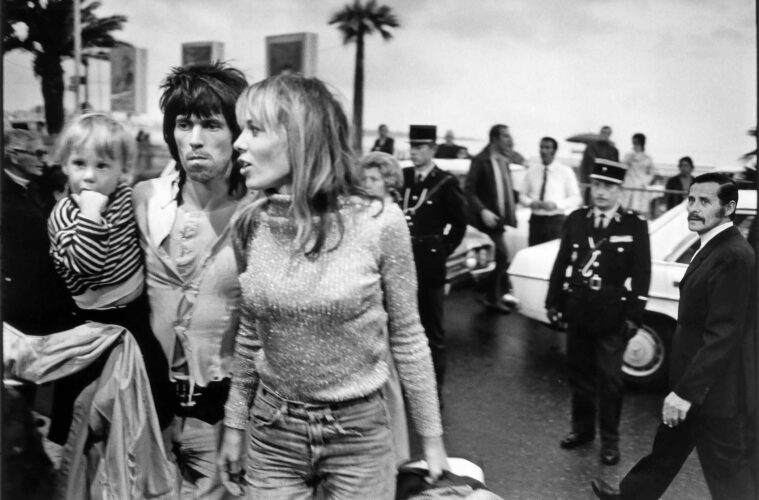

© MICHAEL COOPER. PHOTO COURTESY OF MAGNOLIA PICTURES.

The second half of the film is dedicated to the relationship between Richards and Pallenberg, which lasted from 1967 until 1980. They had three children, one of whom died in his crib at only two months old, a tragedy that likely pushed Pallenberg to increasing drug and alcohol use, which continued well into her middle age. The movie features poignant interviews with her son Marlon and daughter Angela, who detail a chaotic upbringing during which their mother struggled with heroin addiction while their similarly drug-addled father toured the world. But nothing exemplifies their lackadaisical and tumultuous childhood like the footage of the couple’s chateau in the south of France, during the recording of 1972’s Exile on Mainstreet. In these home movies we see musicians, drug dealers, and other miscreants passed out in a large living room, as the kids jump over their bodies like obstacles in a playpen. The footage is not only shocking but an honest depiction of a time when rock and roll and a debauched lifestyle were inextricably linked.

With a treasure trove of archival footage, Catching Fire is a notch above most rock docs. The filmmakers never depend on talking heads or cheap dramatizations to tell Pallenberg’s story; it’s all there in grainy home recordings. Whether we’re in Cannes, Switzerland (where the couple shared an idyll for a short time), London, or upstate New York, where their children were eventually raised, the Super 8 movies are like time capsules that stylishly unfold with the narrative. One might wish, though, that the movie spent more time with Pallenberg in the third act of her life. It’s an interesting chapter, during which she entered recovery from years of drug abuse, received a degree in fashion and textiles from Central Saint Martins, a London art school, and seems to have discovered a certain peace. But the final part of the film feels rushed. Still, this is one of the best music docs in years, a journey into the allure and darkness of rock and roll and the consequences that come with it. Pallenberg, who died in 2017, wasn’t just a survivor, she was a formidable and spirited figure who cemented her reputation as a style icon and a historical figure in rock and roll. Or, as Richards fondly recalls: “She was a unique piece of work.”

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.