Paradise and the Abyss in new Found Footage Films — Three Minutes: A Lengthening and The Super 8 Years both discover that reality and film live different lives.

Paradise and the Abyss in new Found Footage Films — Three Minutes: A Lengthening and The Super 8 Years both discover that reality and film live different lives.

For what it’s worth, 2022 is shaping up as a movie year overrun with movies about movies. You can’t be surprised, given the COVID-fueled toggle toward hunkering at home, that filmmakers and viewers alike would indulge in cinephiliac retrospection and go all Cinema Paradiso on yesteryear modes of production and theater viewership. Enter The Fabelmans, Empire of Light, Babylon, Blonde, Bardo, Last Film Show, even Gaspar Noe’s Lux Æterna, Ethan Hawke’s The Last Movie Stars, and Marco Bellocchio’s Marx Can Wait: film directors portrayed as vexed and dreamy modern heroes, old-timey movie palaces raked by projector beams, and back-in-the-day mass movie-watching of the kind that has suddenly become as contemporary as pay phones.

Ironically, these films will mostly be seen on home screens, of course. But that’s not quite the disruptive cultural trend it’s made out to be—home-viewing is older, in fact, than television, thanks to the time-honored meta-media known as home movies. Used to be, since at least 1923, many of us would collect as families, or as preteen budding cineastes like Sammy Fabelman, to watch self-shot, self-projected film on living room walls or hung sheets—acts of viewership that could hardly be more intimate, private, and transcendent. It’s a forgotten analogue dynamic today, although safety-film celluloid and even magnetic tape commonly out-survives its users, and TikTok videos have virtually no way of lasting, vanishing into the ether by the millions.

This year we have two distinctive found-footage films made up entirely from old home movies: Bianca Stigter’s Three Minutes: A Lengthening and Annie Ernaux and David Ernaux-Briot’s The Super 8 Years, both of which investigate their footage for what it reveals about history and what it fails to document. The sense of time being crystallized and then microscopically dissected, instead of disappearing forever, is dizzying, as it was for Garrett Bradley and Fox Rich in the aptly titled home-movie-indexing doc Time (2020), and even the grown daughter briefly seen in Charlotte Wells’s Aftersun (2022), hunting through childhood vacation videos for a clue about her father’s life.

In a real sense, all of these films address a quotidian dynamic we all face—that our lives are atomized moments in time we cannot truly hold onto, though we try, tirelessly, with the only organic mechanism we have: memory. But memory is worse than fallible, and so we film. Once a moment is caught in a movie, it stays unchanged more or less forever, but what also becomes evident to us is how many questions go unanswered, how much about a person or place or action is not capturable, how much we don’t know about a thin slice of life just by looking at it, as it was once beheld by a camera lens. Of course, as time passes, home movies become about death, lost children, younger and more beautiful versions of ourselves, vacations we can hardly remember, happinesses long since extinguished—ordinary passages of life that, despite the fact that we can see them, remain out of reach, evaporated into the past.

Naturally, both features have hidden auteurs—the two men who held the cameras so many decades earlier, who are helplessly also off-screen subjects in the new movies. Three Minutes: A Lengthening is, as the title says, an extrapolation of three minutes of 16mm footage taken in 1938, of a visit to the Jewish neighborhood in the small Polish village of Nasielsk. The cameraman was David Kurtz, an Americanized Polish Jew who, after building a business in America, went with his wife and friends on a European Grand Tour and, in Warsaw, detoured alone in a rented car to the place of his birth. We never see him, but the village comes out in a throng to see the rich American with his camera (a new Magazine Cine-Kodak), and he pans the crowd’s performative faces and the comings and goings of storefronts, recording the trip but also looking, presumably, for some liminal trace of his family and himself in this sunny corner of Poland. Of course, the war was coming, and nearly everyone on view would be annihilated in just a few years. (The film notes that the footage stands as one of the very few instances where a prewar Polish town was preserved on film.) Nine decades later, for her part, Stigter Zapruderizes Kurtz’s footage, atomizing it into evidence, from family physical traits to coat buttons, mezuzahs, hats, barely readable store signs, and so on, in a largely vain effort to recover these lost Jews from the abyss of the forgotten dead.

In this way, Three Minutes embodies the cultural appetite that has made Ancestry.com and 23andMe American obsessions; the film is its own genealogical rabbit hole. A man with a perhaps routine yen for discovering family roots, Kurtz returned home to New York before the war broke out; his great-grandson Glenn found the small spool of 16mm in 2009 and had it restored. Now, Stigter struggles to do what Kurtz couldn’t—her film essentially climaxes with an honorary yearbook-style portrait collage of every face in the film, all 153 of them, some identified (one 13-year-old kid is picked out by his Detroit granddaughter 70-odd years later), most left nameless. The film’s payload of information, while vivid and rich, is also threadbare in any practical sense, so the unknowing, the lack and the loss, is the film’s ultimate thrust. Preserving the image of an ephemeral instant doesn’t, in the end, freeze time so much as remind us how most of life will always slip through our fingers.

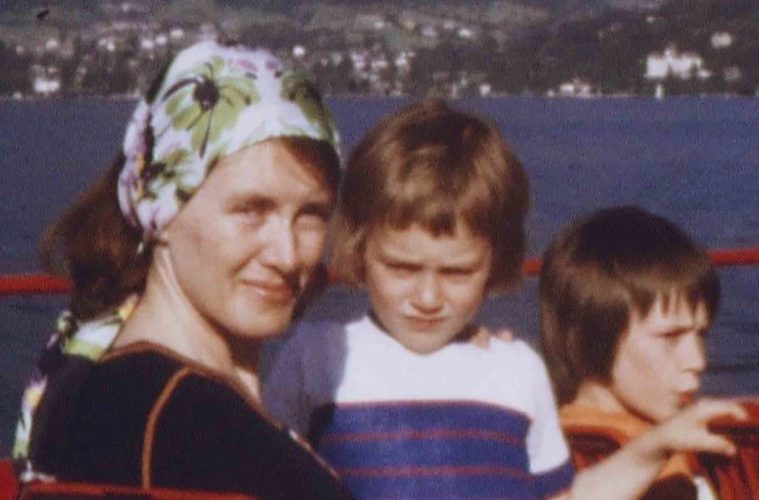

Without the Holocaust haunting it, the Ernaux film, The Super 8 Years, is similarly consumed by distance, while exuding a different sense of crisis. Annie Ernaux, the French autofiction celebrity recently anointed with both a Nobel and a potent film adaptation of her 2000 fictionalized illegal-abortion memoir Happening, narrates the footage, and thus provides the narrative, even though the cameraman is her husband Phillippe, who doubtless had his own ideas and feelings about what to film and why. These are paradigmatic Super 8 home movies from the ’70s, now edited together by Ernaux’s son, David, and presented more or less straight, recording the holidays and vacations of a somewhat posh married couple with two young kids. They travel all over Europe and as far away as Chile, and Phillippe’s footage focuses on local sights and the three-quarters of the family in front of the camera semi-comfortably performing as themselves.

But, as Ernaux’s prosy narration tells us in tense detail, we’re not seeing what really happened, what went on beneath the surface of the family and the marriage. How could we? She frames the footage entirely from her point of view, commenting on the action’s “theatricality,” “tinged with violence,” and giving voice to her then-unexpressed feelings of suppression, frustration, and helplessness within the traditional roles of wife and mother, even as she tastes success with the publication of her first books. Her voice is immediately recognizable from her books—she even toggles here between referring to herself as “I” and “she”—and is as doggedly solipsistic. Whatever the rest of the Ernaux family might have been feeling, or how they might feel about this old footage today, isn’t on the table—neither, oddly, is Ernaux’s sense of how it is to look back upon her lovely self 50-odd years later, a dynamic that’s at the poignant heart of home movies as a form. The takeaway text of the film hews only to the writer’s memory of being simmeringly unsatisfied with her trad life at the time. But no matter how much Ernaux insists on the story of her inner turmoil, the Super 8 films themselves surge with everyday family feeling. There’s more there than Ernaux’s clenched sense of self. After a visit to Moscow, the marriage “collapsed” off-screen, and we’re told that Phillippe got the camera, while Annie got the films and the projector, aptly dividing for Ernaux the past from the future.

What’s been termed ephemeral film—from institutional and educational movies to TV commercials, stag reels, and beyond, representing the true majority of filmmaking in the last century-plus—is often pregnant with the potential to be reused, recontextualized, reimbued with meaning. Who needs a camera to make a movie, with all this stuff laying around? Sometimes, you don’t need to do anything to the footage to have it reawaken into something new—in 1985, experimental-film legend Ken Jacobs bought a reel of discarded news footage, interviews shot after the assassination of Malcolm X, and simply presented it as is, titling it Perfect Film. In 2011, Romanian filmmaker Andrei Ujica simply assembled, without commentary, official footage from 25 years of the Ceausescu regime and titled it The Autobiography of Nikolae Ceausescu, thereby letting the dictatorship dig its own propaganda grave. It’s a strategy Ukrainian master Sergei Loznitsa has also been using with old Soviet footage for the past 20 years, in scores of features and shorts, like a one-man truth-and-non-reconciliation committee.

Home movies are merely the most intimate materials on hand, as you can see yourself every year since 2003 at Home Movie Day, a loosely organized annual showcase of old home movies that occurs all over the world, and in New York has been hosted by MOMA, Museum of the Moving Image, Bat Haus in Williamsburg, Cinema Arts Centre in Huntington, various borough libraries, and elsewhere. You can bring your own films, or even organize your own event. (See CenterforHomeMovies.org for helpful instructions.) You may not have the Holocaust or a Nobel Prize to lend your footage gravitas, but certainly the point of Home Movie Day, as a global phenomenon, is that your rough little pockets of captured time, however fragmentary and incomplete, are more than enough.

Editor’s note: The disclaimer below refers to advertising posts and does not apply to this or any other editorial stories. LA Weekly editorial does not and will not sell content.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.