Family caregivers help disabled family members or friends with activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). They are designated as informal caregivers because they are not affiliated with a paid service. Family caregiver support is usually unpaid and voluntary. According to AARP, the relative value of care provided by 41 million informal caregivers in 2019 was about $470 billion, amounting to 2 percent of the United States’ Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Beyond the enormous value of the services performed, it is estimated that one-third of family caregivers keep performing their caregiving tasks while supporting their own health issues. Moreover, about half of them are experiencing depressive symptoms. The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has made their already demanding work even more difficult.

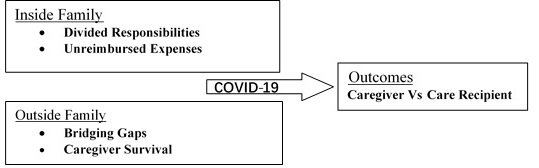

Identifying the challenges faced by family caregivers helps us to understand the complex nature of their work and gives us insights into providing the support they require to overcome these challenges. As close friends and family members, we can view their caregiver role through the lens of family dynamics, which is how family members interrelate. Five common tensions may be identified in this context. We believe that balancing these five tensions can refine the nature of their tasks and sustain them as healthy, purposeful caregivers.

1. COVID-19 Challenge. The outbreak of COVID-19 is an external challenge that complicates caregiving. Care recipients are usually at significantly higher risk for infection and may be exposed to the disease in senior care facilities, which are considered high-risk places, because they may have to go through medical procedures for their chronic issues. That also increases the possibility for caregivers to be exposed to a risky environment. How caregivers should protect themselves and care recipients is a serious question they have to face. First: Heal Thyself.

2. Divided Responsibilities. A family caregiver may have one or more family helpers to supplement ADL and IADL care. Different helpers may rotate periodically or assume responsibility for different care tasks. How should the tasks be divided to make the them acceptable to everyone providing care? In the real-world, pre-determined plans may be changed or interrupted unexpectedly. We recommend relegating the duties as clearly as possible, with explicit back-up plans, including all helpers in the planning stages to facilitate mutual understanding among those providing care.

3. Unreimbursed Expenses. In some cases, caregivers pay some of the costs of care from their own pockets and are not reimbursed, increasing caregiver financial strain and diminishing motivation to continue providing support for the care recipient. A possible solution to this issue is to develop a signed agreement for the caregiver to withdraw money from a family account on in a well-defined manner to cover incidental expenditures. In that way, caregivers are reimbursed and the rest of the family is protected by account transparency.

4. Bridging Gaps. An AARP Report (2020) indicated that more than 60 percent of family caregivers have crossed and recrossed the bridge between full-time jobs and caregiving responsibilities. Their challenge is to cope with dual roles, while shifting smoothly from one to another. For example, in their work life, caregivers may be thinking of their care recipient’s needs and, when they are performing caregiving tasks, they may be considering their day-job performance. These distractions complicate their lives and jeopardize both.

5. Caregiver Outcomes. All of us have been care recipients; many of us will be caregivers, and eventually, if we survive, care recipients, again. If tensions inside and outside family are not constrained, a caregivers’ mental and physical well-being may be negatively impacted. The fact is that, occasionally, care recipients outlive caregivers. Being a caregiver is physically and emotionally demanding, so caregiver health and well-being merits attention. The Family Caregiver Alliance Learning Center (FCA) suggests that family caregivers are prone to the following risky behaviors:

- Sleep deprivation

- Poor eating habits

- Failure to exercise

- Failure to stay in bed when ill

- Postponement of or failure to make medical appointments for themselves

- Untreated depressive symptoms and alcoholism

The mission of the FCA is to improve quality of life for family caregivers and those who receive care. If you need further information or wish to comment, please contact the author: doctorgeorgeshannon@gmail.com

George Shannon, MSG, PhD, Director: Rongxiang Xu Regenerative Life Sciences Lab (RxX Lab); Mengzhao Yan, MA; Erin Crutcher, MSG Candidate; Research Assistants, RxX Lab; USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.