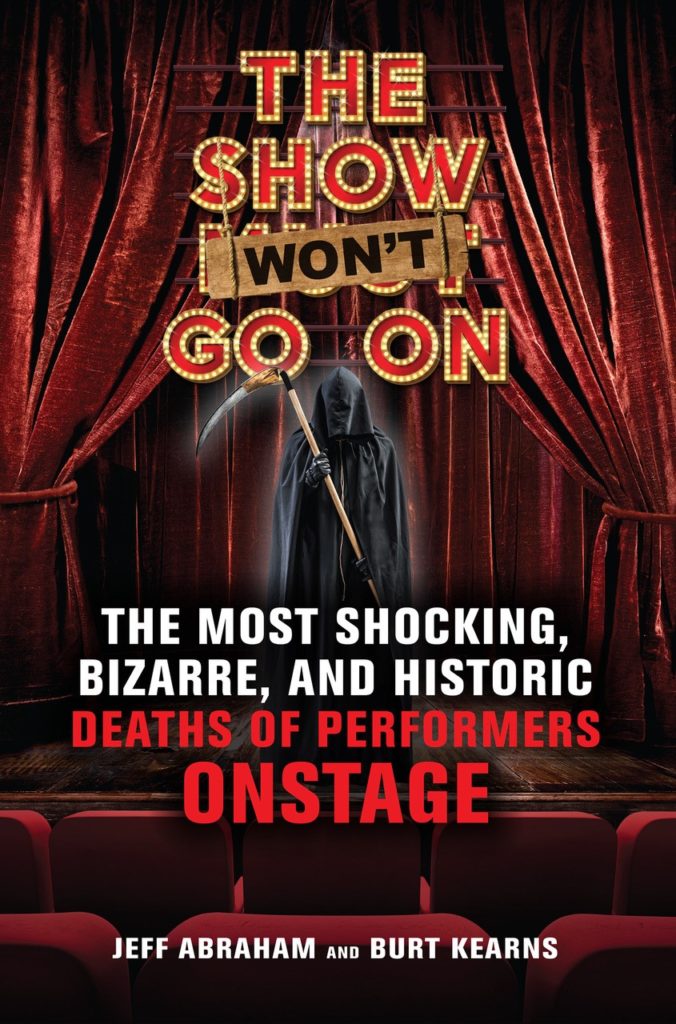

Jeff Abraham and Burt Kearns’ new book The Show Won’t Go On concerns a subject matter that should appeal to fans of morbid history but also entertainment in general. Rock & roll suicides, murders, electrocutions and medical emergencies are recounted in thorough detail in the book — subtitled “The Most Shocking, Bizarre, and Historic Deaths of Performers Onstage.” The authors tout the collection of death stories as “the first comprehensive study of the phenomenon of performing artists who shuffle off this mortal coil mid-song, mid-solo, mid-concert.” For rock music fans the murder of Dimebag Darrell from Pantera in Ohio probably tops the list of unforgettably tragic on-stage deaths (and it’s of course included here) but there were other less dramatic life departures, and as the book illustrates most of the time the audience didn’t even know what was happening, thinking it was part of the show. L.A. Weekly asked the authors to share a couple of L.A. based stories from the book, and they gave us two tales of musicians who took final bows in landmark San Fernando Valley nightclubs, excerpted below.

Abraham and Kearns will read and sign the book at The Dearly Departed Museum located at 5901 Santa Monica Boulevard in Hollywood; Sat., Oct. 19, 5 p.m.; free. Also at Stories Books & Café, 1716 W. Sunset Blvd., Echo Park, Tue., Oct. 22, 7:30 p.m.; free. For more info on the book go to theshowwontgoon.com/.

Two Nights In The Valley- Nick Menza & Warne Marsh & All That Jazz Rock

What better place for a wild, extreme, heavy metal drummer to beat his last skin than in a cozy jazz club? The club was the Baked Potato, a cool little spot in Studio City, California, just down the street from Universal Studios. The jazz promised to be a little less cool and a lot more explosive on May 21, 2016, when a trio of heavy metal legends took over the Baked Potato’s small stage.

OHM was a progressive jazz rock fusion group led by guitarist Chris Poland, who twenty years earlier was headbanging with thrash metal band Megadeth. Bassist Robertino Pagliari had held the bottom for metalists Divine Rite. Between them, wielding sticks behind an extravagant orange drum kit that took up most of the stage, was the heaviest metal legend of the group. Nick Menza had joined Megadeth in 1989, two years after Poland’s departure. He pounded the beats on Megadeth’s most successful albums, including Rust in Peace and Countdown to Extinction, and was with the band for eight years, until he was sidelined by a benign tumor on his knee and ultimately given the boot.

Nick Menza (Courtesy The Show Won’t Go On)

Promotion of his subsequent solo album, Life After Deth, hit a speed bump in 2003 when guitarist Ty Longley set out on tour with the reformed Great White — and was killed in the Station nightclub fire in Rhode Island. A year later, Menza’s bassist Jason Levin died of heart failure.

Menza had his own close calls. In 2007, he almost lost an arm in a gruesome run-in with a rusty power saw. He recovered and auctioned off the bloody saw blade and X-ray to a lucky fan. When he joined OHM in 2015, he was the sixth sticksman to occupy the throne, replacing David Eagle, who died that August after a heart attack and open heart surgery. (Menza was the seventh drummer if you count Gar Samuelson, who was to be the third piece in the original lineup when he died of liver failure at forty-one). With enough death and mayhem in his past to fill a book , Menza decided to do just that: He was planning to fly to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, after the Baked Potato gig to finish a comic book version of his autobiography, Menza-Life (ultimately released as Megalife).

While some fans thought it strange that the power drummer wound up playing in a tasteful jazz club, the music of OHM was not a far cry from the jazz that Menza’s German-born father Don Menza played in his years blowing tenor sax in the Tonight Show band. Though the Baked Potato had been a jamming room for many Tonight Show musicians before the show was moved back to New York City in 2014, it also made room for outfits like OHM that played a fiery, precise, Jeff Beckian jazz rock, full of blazing solos and tricky time signatures.

On the night of May 21, Chris Poland recalled, Nick Menza played with an intensity “like I’d never heard before. It’s not the volume intensity; it’s just how intense he was playing it,” he said on the podcast As the Story Grows. “He had a fire under his butt. It was the best I’ve ever heard him play drums…

“We get to the end of the third song, which I think was ‘Peanut Buddha,’ and… my guitar, where the right arm is hitting the body, is all wet. I’m drying myself off, and he goes, ‘Dude, are you OK?’ I go, ‘No, I’m good.’

“He tightened his high hat, and he sat his hands down on his lap, and then he just leaned over into the monitor. I thought he was fucking with me. He’s still there, and I said, ‘Hey, man, let’s go.’ I thought, ‘Of course he’s messing with me.’ I said, ‘Nick, come on, man.’ I look over, and his eyes are open. That’s when I knew that something had happened. I couldn’t believe it.”

Two patrons rushed to the stage and began CPR until EMS arrived. The paramedics worked on the drummer for more than twenty-five minutes. They gave him shots of adrenaline, three shocks, and nonstop chest compressions.

(Courtesy Chicago Review Press)

None did any good. Nick Menza was gone at the Baked Potato and pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital. He was fifty-one. The Los Angeles County Coroner would rule that Menza died of natural causes: a heart attack as a result of hypertensive and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. In the days to follow, his manager Robert Bolger said that friends and family took some comfort knowing that on several occasions Nick Menza said that when he died he wanted to do so onstage.

*******

Then there’s the story of that night at Donte’s and the jazzman who dropped from out of nowhere.

Donte’s jazz club opened as a piano bar on Lankershim Boulevard in North Hollywood on June 22, 1966. Hampton Hawes was featured on piano, with Red Mitchell on bass and Donald Bailey on drums. By winter, the piano bar was replaced by a bandstand, and Donte’s was on its way to becoming the hippest, hottest jazz club in Los Angeles. Donte’s hosted big-name jazz stars like Chet Baker, Al Cohn, Zoot Sims, Art Pepper, Joe Pass, and Pete Jolly. Stan Kenton, Buddy Rich, Woody Herman, and Count Basie brought in their big bands. Doc Severinsen, Tommy Newsom, and the Tonight Show Band would set up after their regular gig with Johnny Carson in Burbank. Comedians like Redd Foxx and Mort Sahl liked to try out new material in the room. Celebs including Clint Eastwood, Frank Sinatra, and Pearl Bailey mixed with the locals.

Donte’s held on for more than twenty years. By the final weeks of 1987, the place was worn out. The IRS had shuttered it more than once. The owner, old Carey Leverette, had to thank local musicians like Ross Tompkins, who kept up a regular weekly jam with his Thursday Night Band. Tompkins had a regular gig as pianist for the Tonight Show Band, so he never hassled the owner about late or bounced paychecks.

Donte’s (Courtesy The Show Won’t Go On)

December 17, 1987, was a Thursday night, and the Thursday Night Band was on the bandstand. Led by Tompkins, with Buddy Clark on bass and drummer Larence Marable, the quartet usually included Tonight Show trumpet player Conte Candoli. Candoli couldn’t make it on this night, so a call went out in the afternoon to a tenor sax player named Warne Marsh.

The name Warne Marsh, often misspelled on marquees as “Warner” or “Wayne,” may not have been a household one, but among jazz enthusiasts it was highly respected. Warne Marsh was lauded as one of the best improvisers in jazz history. Downbeat, the jazz bible, described him as “a tenor saxophonist of immense resourcefulness and great technical command… a truly innovative and original musician and a master of the particular jazz art of instant composition.”

Marsh first got attention in the late 1940s as a student of and player with reclusive, blind avant-garde pianist Lennie Tristano, bringing improvisation to new directions and heights. He was also a founding member of Supersax, a band conceived in 1972 to play harmonized arrangements of Charlie “Bird” Parker’s saxophone solos with a saxophone section.

Warne Marsh (Courtesy The Show Wont Go On)

He was a cult figure, though his recordings were scattered. Marsh was a daily marijuana smoker, and liked his amphetamines, cocaine, and occasionally heroin. The afternoon he got the call to fill in for Conte Candoli, he’d been taking a nap after getting high and doing lines with other musicians at a music store in Hollywood.

There wasn’t much of a crowd at Donte’s when the Thursday Night Band took their places on the stage. Warne Marsh called the tune to open the second set, a favorite of his called “Out of Nowhere.” He performed his solo as expertly as ever, and when he was finished, stepped back and sat on his stool. Then he stepped off and staggered. Gene Lesner, an amateur sax player and Donte’s regular, was in the room. In Safford Chamberlain’s book An Unsung Cat: The Life and Music of Warne Marsh, Lesner related that Marsh then “gently laid his horn on the floor, and lay down on his side… It was so slick, so smooth, the way he went down. Everyone of course knew that he’d had that heart attack.”

The drummer called out: “For Christ’s sake, somebody call an ambulance!” The lights went on. Warne Marsh wasn’t moving. There was a small puddle of vomit by his mouth.

It seemed a long wait for the ambulance, though it probably arrived within about ten minutes. By then, Warne Marsh was already dead. Someone covered his body with a coat. The paramedics tried some CPR and drove him to St. Joseph Medical Center in Burbank, where doctors pronounced him dead early Friday morning. He was sixty.

The band never got paid at all that night. Old man Carey Leverette said they didn’t deserve to, because they didn’t finish the set. Four months later, he announced he’d sold Donte’s to a Japanese businessman. Two days after that, the sale of the club closed escrow. The next day, Leverette was found dead in his cluttered office. He was sixty-three.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.