Originally published by the Village Voice.

Rapper’s Delight: Michael Wright — better known as Wonder Mike, of the Sugarhill Gang — was working at a candy factory in New Jersey when he penned some of his first rhymes. With a strong aroma of jelly beans, chocolate-covered peanuts, toffee, and buttermilk wafting in the air, the Newark native’s inevitable sugar rush fueled his creativity, and for a moment he felt like anything was possible. Earlier that day, his cousin had introduced him to something called “hip-hop,” a cultural movement exploding in the Bronx.

“It was May of ’79 when my cousin came up to me with a boombox,” he remembers. “I had never seen a boombox. I didn’t know what it was. It was just really big and it was blasting this thing called rap. It wasn’t anybody known really, just some bullshit guy. I was into hard rock at the time, so I thought, ‘Wow, this sucks.’”

Undeterred by Mike’s dismissive reaction, his cousin — who went by the rap moniker Daddy Wright — encouraged him to show up at a party, where he became immersed in this intriguing new phenomenon unfurling in New York City. “It was May 28 — I’ll never forget,” he says. “What I heard was totally different from that joker I heard on that boombox. It was my cousin and his friends, and they were taking turns rapping. They were clever with it.”

That night, Mike grabbed ahold of the microphone and rapped for 90 seconds, just long enough to unlock his passion for rhyming. About six weeks later, he christened himself Wonder Mike. But by August ’79, he’d fallen on desperate times. The 22-year-old had lost his job, was homeless, and had essentially depleted his prospects. The occasional odd job — which included cutting down trees and moving furniture — would momentarily put food in his belly, but his situation was growing more dire by the minute. Wonder Mike was down to his last dollar when Sylvia Robinson came knocking on the proverbial door. The co-founder of Sugar Hill Records and one-half of the defunct R&B group Mickey & Sylvia, Robinson was well-versed in the music business. She, too, was enamored by the emerging sounds of hip-hop, and just as curious about its potential. Somehow — and this still eludes Mike to this day — a DJ friend of his learned that Robinson wanted to make a record and was actively recruiting MCs for the project.

It’s been a long journey from that candy factory in New Jersey. (C.S. Muncy)

“Legend has it Sylvia and her son Joe were on Palisade Avenue in Englewood, and they knew of a rapper who went by Big Bank Hank because he used to make pizzas and rap while making them,” Mike says. “My buddy Casper had already turned them down, so they did a U-turn and sent Joe into the pizza shop. ‘Hey, my mother is making a record and wants to hear you. Get in the car.’”

With pizza sauce and cheese splattered across his apron, Big Bank Hank eagerly hopped into Robinson’s car and proceeded to rattle off a few bars that quickly earned her approval. Meanwhile, Master Gee — another aspiring rapper from New Jersey — had just made a call from a phone booth down the street from the pizza shop. As he strolled by, he overheard Big Bank Hank rapping and inserted himself into the makeshift audition: “What’s this? What y’all doing?” With that, Master Gee started rhyming. Robinson heard enough and asked them to come over to her New Jersey mansion, where there was a better sound system. Wonder Mike got the address for the audition, picked up his DJ, and headed over. Once they were set up at the house, he pulled from his experience with homelessness and rhymed about a “hotel motel, Holiday Inn,” and Robinson, as Mike remembers, was “digging it.”

That night at the Robinsons’ mansion, Big Bank Hank, Master Gee, and Wonder Mike united as the Sugarhill Gang. Their inaugural single, “Rapper’s Delight,” was recorded at Sugar Hill Studios in a matter of days. With the help of a band called Positive Force, who recreated the music from Chic’s 1979 disco hit “Good Times” for the Sugarhill Gang to rhyme over, the Robinsons orchestrated an instant party anthem, weaving disco and hip-hop into one sonic tapestry. Other samples included “Here Comes That Sound Again,” by Love De-Luxe with Hawkshaw’s Discophonia (1979), and “Fun Loving Rapping,” from the movie Five on the Black Hand Side (1973).

Once the song was finished, everyone was ready to retreat to their respective homes — except Wonder Mike, who still had nowhere to go. In an effort to stay someplace warm, he repeatedly told Robinson he wanted to “do it again,” despite the fact that it was 3:30 in the morning.

“Everybody’s getting in their cars and going home to their nice houses they took for granted,” he recalls. “They could go to the bathroom, they could certainly eat, and they were gonna sleep on a pillow. I stood there until everybody left, and I was going to go across the street to the park. Mrs. Robinson stopped the car and said, ‘Where are you going?’ I said I was waiting for my cousin. She said, ‘No, you’re not. You going across to that park, aren’t you?’ She told me to get in the car. I went from the park to a seven-bedroom Spanish-style mansion with a heated swimming pool in the back.”

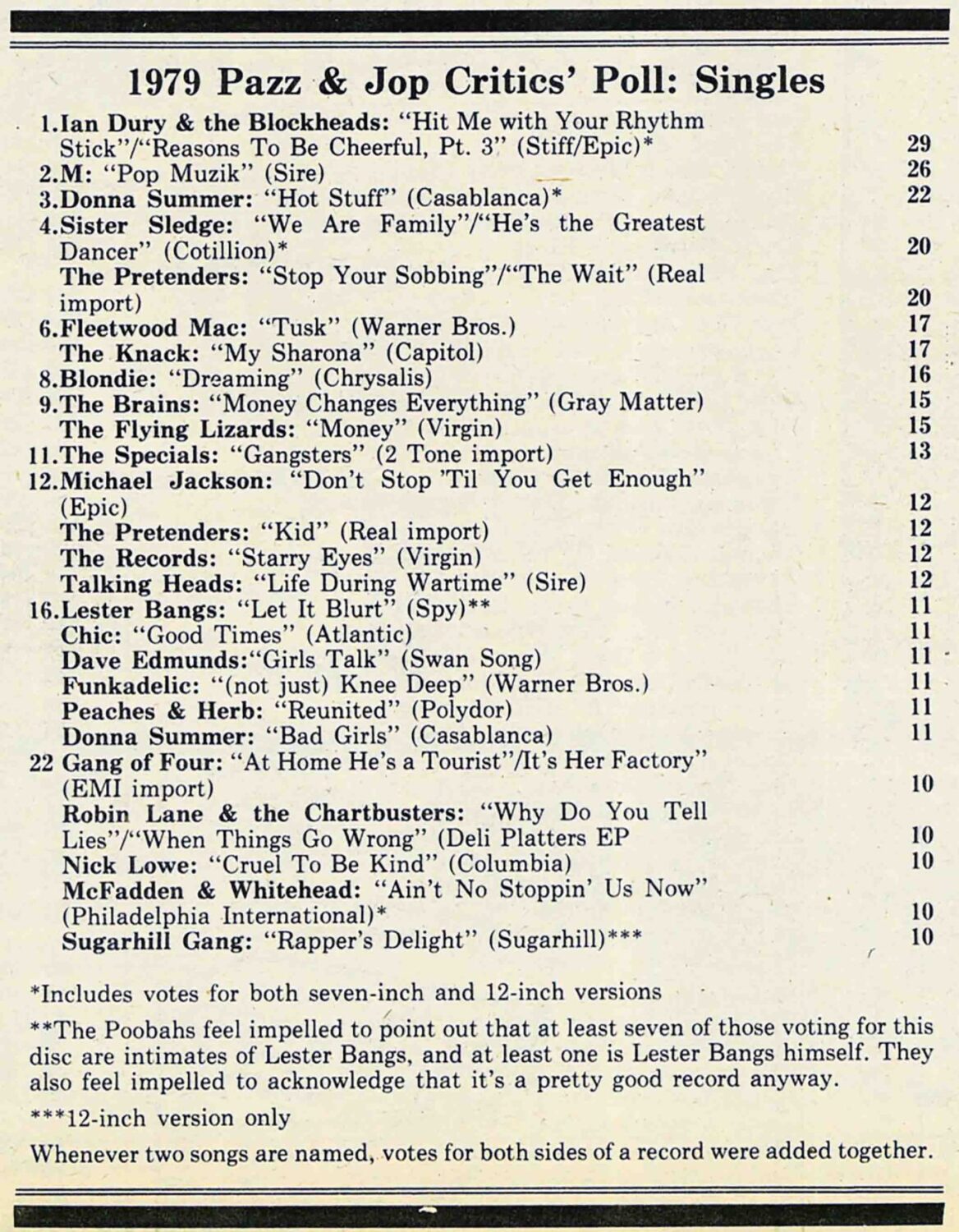

From the January 28, 1980, issue of the Voice: “Rapper’s Delight” — the 12″ version only — just made it into the top 25 singles in the 1979 Pazz & Jop poll. (Village Voice Archive)

Wonder Mike’s luck was beginning to change. “Rapper’s Delight” was a bona fide hit, peaking at No. 36 on the Billboard Hot 100, No. 1 on the Canadian Singles Chart, No. 3 on the U.K. Singles Chart, and No. 1 on the Dutch Top 40 — but it wasn’t without controversy, then and later. In the second verse, Big Bank Hank raps, “Check it out, I’m the C-A-S-AN, the O-V-A and the rest is F-L-Y,” the nickname of local DJ/rapper Grandmaster Caz. As Mike explains, Big Bank Hank used to do security for Grandmaster Caz and was able to get his hands on one of his notebooks. While ghostwriting — writing lyrics on behalf of someone else who’s then credited as the creator — is common in hip-hop today, back then it was universally frowned upon.

“Hank used to rap so much at the pizza parlor, but he didn’t have his own rhymes,” Mike says. “He was always saying Caz’s rhymes, so when it came time to record the record, nobody knew they weren’t Hank’s rhymes. In fact, that weekend Hank went to Caz and said, ‘This lady wants us to make a record. Can you help me out with some rhymes?’ And Caz tossed some notebooks on the table and said, ‘Take what you need.’ He thought maybe he’d take a verse or two — not 15 minutes’ worth. Hank never gave it up about who wrote the rhymes, because back then, if you didn’t write your rhymes you were considered wack.”

Nobody in the Sugarhill Gang heard from Grandmaster Caz after the song’s release. When they finally did run into him, 15 years later, Caz never asked for royalties nor did he demand credit. “I never understood why,” Mike admits.

But at the time that “Rapper’s Delight” was a hit, the group was confronted with a brewing legal battle over the use of Chic’s “Good Times,” which had electrified clubs that entire summer. Lead singer Nile Rodgers and bandmate Bernard Edwards were initially furious, and threatened legal action against the Sugarhill Gang and Sugar Hill Records. But eventually, a settlement was reached between all parties, and Rodgers and Edwards were ultimately credited as co-writers.

Taking the air with longtime girlfriend Florella Adams. (C.S. Muncy)

“I didn’t know anything about music, but I knew we didn’t write that music,” Wonder Mike says. “The fucked up thing is we put our names on it and not theirs when it first came out. When the court thing came through, they put their names on it and ours were taken off. I thought that was bullshit. It should have been our names and theirs. We did the rhymes and they did the music. Fair’s fair. That’s not even Chic on the record. We had Positive Force recreate it.”

With that issue in the rearview, the Sugarhill Gang still had to contend with naysayers who questioned their authenticity. New York City–bred DJs such as Grandmaster Flash, Kool Herc, and Afrika Bambaataa felt that Robinson had more or less ripped them off.

“Everybody was upset,” Mike says. “Like, ‘Who are these guys? They’re from New Jersey.’ We were really looked down on. I didn’t give a flying fuck. I was homeless and now was off the street and making money, so kick rocks. Rap was out for six years before ‘Rapper’s Delight.’ We did something with it!”

Despite the track’s complicated history, “Rapper’s Delight” helped introduce hip-hop to a global audience and inadvertently blazed a trail for it to blossom into the biggest genre in the world. The song now lives in the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry, alongside myriad other influential works, such as “Crazy,” by Patsy Cline; Nevermind, by Nirvana; and Fear of a Black Planet, by Public Enemy.

“We didn’t invent hip-hop, but we helped start the culture and make it big,” Wonder Mike concludes. “And nobody’s gonna take that well. People are gonna be like, ‘Well so and so did it first.’ Who gives a fuck? I didn’t say I started it. Back then, it was only in New York. Now it’s in New York, Belgium, Russia, the Netherlands, Africa, Australia, Seattle, Texas, California. You name it. It’s everywhere.” ❖

Rapper’s Delight: Kyle Eustice is a veteran music journalist with a focus on hip-hop. After a stint at The Source, she spent six years at HipHopDX, where she pumped out more than 12,000 articles. She is now a senior editor at Hits magazine and simultaneously maintains freelance gigs at Thrasher, Chuck D’s RAPstation, and High Times. Other bylines include Rolling Stone, Spin, Variety, Rock the Bells, and Wax Poetics, among others.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.