Mary Harron’s Daliland struggles to find itself, amid a predictable arsenal of biopic cliches and actor-y impersonations. Given the deliberate outrageousness that infused everything about Salvador Dali, from his performance-art-ish public stunts to his six-decade career of sui generis art-making, you’d think there’d be a movie to be made about him. But maybe there isn’t — biopics are a tricky business, dizzy with mere celebrity and often starved for dramatic justification, and if your subject was world-famous, successful, and didn’t die tragically young, there won’t be a helluva lot of protein in your trail mix. Dali was a wildly effective self-promoter and eccentric hedonist as well as a spectacularly gifted image-maker, all the way up to a few years before he died, and the only dilemma he seemed to face was that he, and the in-vogue-ness of his art, couldn’t last forever. It’s a life — one that must have been a champagne-gassed roller-coaster limo ride, certainly — but not a story.

Mary Harron’s Daliland struggles to find itself, amid a predictable arsenal of biopic cliches and actor-y impersonations. Given the deliberate outrageousness that infused everything about Salvador Dali, from his performance-art-ish public stunts to his six-decade career of sui generis art-making, you’d think there’d be a movie to be made about him. But maybe there isn’t — biopics are a tricky business, dizzy with mere celebrity and often starved for dramatic justification, and if your subject was world-famous, successful, and didn’t die tragically young, there won’t be a helluva lot of protein in your trail mix. Dali was a wildly effective self-promoter and eccentric hedonist as well as a spectacularly gifted image-maker, all the way up to a few years before he died, and the only dilemma he seemed to face was that he, and the in-vogue-ness of his art, couldn’t last forever. It’s a life — one that must have been a champagne-gassed roller-coaster limo ride, certainly — but not a story.

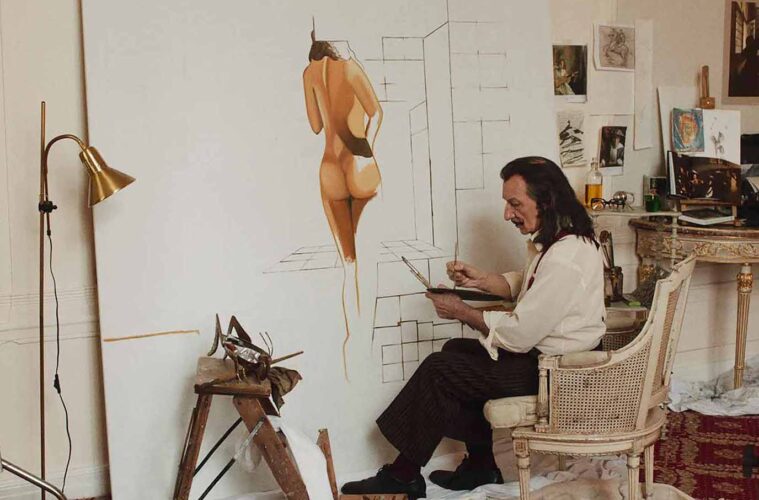

The focus is on the ’70s, with a past-his-prime Dali (Ben Kingsley) holed up in New York’s St. Regis Hotel, throwing shindigs when he’s supposed to be grinding out paintings for an upcoming show. The historical moment is referenced lightly: The art world has passed Dali and surrealism by, in favor of abstraction, pop art, etc. Our entry into the artist’s hermetic little Gomorrah is a fictional innocent, James (Christopher Briney), a budding artist working for Dali’s gallerist who is in no time assigned to assist the splenetic master, and to report back on his progress. The invention of screenwriter John C. Walsh (Mr. Harron), James is a cipher, as these naive eyes-and-ears characters tend to be; the supposedly wild lifestyle he is privy to amounts to flashy hangers-on parties, with Kingsley’s showman holding forth to some acolytes (including Alice Cooper, played forgettably by Mark McKenna) while booze is guzzled and boobs are haphazardly exposed. Cocaine! Lobsters! Three-ways! If only we could’ve been there.

The narrative tries in various ways to plant roots: Dali’s beloved wife, muse, and merciless slave driver, Gala (Barbara Sukowa), screams about money while funding a new boy toy; everyone worries that Dali won’t get the work done; James has a budding but eventually disenchanting romance with one of Dali’s fashionista minions (Suki Waterhouse); an illegal business in Dali prints is hinted at; Dali himself fears aging and dying. None of it ultimately matters, and, shockingly for Harron, the director of I Shot Andy Warhol and American Psycho, none of it is very much fun or very funny. (Sukowa’s outbursts, often involving throwing shoes at people’s heads, are the film’s only spikes of humor.) We get mercifully brief flashbacks, with a young Dali (Ezra Miller, whose Wikipedia page might itself make a seamy biopic) wooing a young Gala (Avital Lvova) and getting the idea of gooey clocks by watching Brie melt.

We don’t get to see The Persistence of Memory, or much other art, which in a film about a great artist is something of an issue. “No one who has seen this picture,” Gala says, “will ever forget it” — but we’re not in that club, apparently, as the painting is kept perversely off-frame. A full-frontal confrontation with the art, and maybe even its making, could have gone a long way toward giving the film the gravitas it lacks, but the filmmakers don’t seem interested. (Maybe it was an estate issue, as with last year’s execrable, entirely-sans-Bowie-music Bowie biopic, Stardust.) In any case, Kingsley does a lovely mock-up of the creaky madcap troublemaker, but he is overshadowed by the excruciating blandness of Briney. Harron is usually a gold medalist at casting, but Briney, whose other credits are limited to a supporting role on the teen show The Summer I Turned Pretty, is a half-lidded bore, with a face so irritatingly pretty (everyone in the film comments on it), you long for Sukowa to hurl a pump at it, heel out.

Ultimately, you realize that Dali himself might be the problem at hand — he was so purposefully, theatrically flamboyant while being so brilliant on canvas that there might not be anything pungent on the inside to explore. Dali may have been the sum total of his skill, his tireless invention, and his appetite for publicity, and that’s it. He was devoted to Gala, for certain, but was also celibate; he loved to stir up trouble (he got himself excommunicated by the surrealists for finding Hitler fascinating and for supporting Franco) and loved having fawning followers around him, as many of us would. So? He was possibly a far simpler person than we imagine, too simple for his biopic to be about anything, in the end, except how much he didn’t want his moveable feast to end. Like us all.

Editor’s note: The disclaimer below refers to advertising posts and does not apply to this or any other editorial stories. LA Weekly editorial does not and will not sell content.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.