When acclaimed scholar Tyree Boyd-Pates joined the Autry as Associate Curator of Western History at the end of 2019, after three game-changing years as the History Curator and Public Program Manager at the California African American Museum, the move may have seemed counterintuitive. But considering that his first priority was to delve into the Autry’s collections and archives with the goal of re-centering the contributions of Black Americans in its narrative, in retrospect it seems more like prescient. When first the pandemic and later the protests made it clear that this is a moment calling out for the formulation of an archive chronicling the new history being made now in real time — one that centers those narratives from the jump — the move starts to seem positively visionary.

Before joining CAAM, Boyd-Pates had been a lecturer of African American Studies at California State University, Dominguez Hills. Inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, Boyd-Pates describes feeling a desire for his expertise and ideas to become more present in the lives of a broader community, and felt that working in the framework of a public destination was a way to accomplish that. In presenting landmark exhibitions including Cross Colours: Black Fashion in the 20th Century (2019), Los Angeles Freedom Rally, 1963 (2018), and No Justice, No Peace: LA 92 (2017), the CAAM team saw their attendance triple.

Tyree Boyd-Pates

Boyd-Pates is inspired by the career and writings of Lonnie G. Bunch III, a historian who was the founding director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, and has been Secretary of the Smithsonian, overseeing its score of institutions and assets since June 16, 2019. Bunch had been the first history curator at CAAM back in 1984, and as Boyd-Pates was examining his own career trajectory, he says, “I saw myself in that story.”

As he told the Weekly in a recent interview, “I started thinking about having a larger impact in American history, and the regional parallel to the Smithsonian is the Autry.” The chance to “poke holes” in the predominant framing of that “Cowboys & Indians” mythology, and build on the progressive foundations being laid there in recent years, was too good to pass up, and he joined the museum.

“I want the general public to see themselves in this history, to focus a new lens on older things, to update the things we think we know by casting fresh eyes on things of historical note,” he says. “I want to represent my community, and bring them into the story.” Of course communities of color and especially Black communities have been present, active, and foundational in the history of the American West from the start. “After Emancipation there was a chance,” he says. “But it’s a time that was never taught in school.” Even just basic fascinating facts like that Compton was an agrarian and equestrian neighborhood, and some 25 percent of the region’s earliest cowboys were Black can flip the script.

Photograph of a farmer and his wife in Compton, California, early 1900s (Autry Collection)

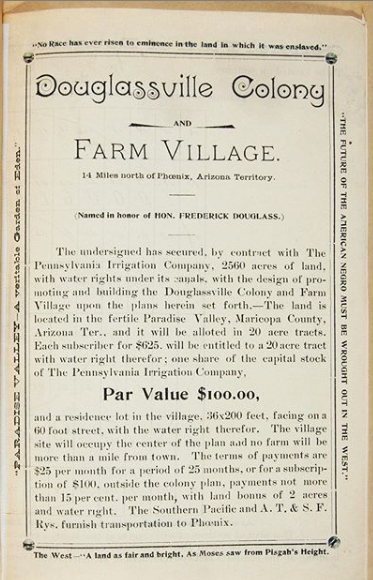

So what has Boyd-Pates found in the Autry collection? “I’m still swimming through it, very much on the journey,” he says. He’s been sharing gems on Instagram and on The Autry Files blog, but there are over 600,000 pieces to get through. “I’m digging for gold,” he says, with his customary, contagious excitement for the work. Examples of documents, photographs, and ephemera speaking to Black history in the west include a portrait of a Black farmer and his wife in Compton in the 1900s; a 1920 photograph of an all-Black musical band on the steps of a courthouse in Elko, Nevada; as well as more dramatic pieces like an 1895 brochure for the never-built Douglassville Colony, a “Freedmen’s Town” in Paradise Valley, AZ.

Douglassville Colony 1895 brochure page one (Autry Collection)

This collection exploration was and is very much still his job; but when the pandemic arrived, the Autry, like everything else, had to pivot. “The pandemic sparked a reimagining of what a museum is and who it’s for,” Boyd-Pates says, referencing his initial decision to curate a COVID collection, Collecting Community History Initiative (CCHI): The West During COVID-19. “The Autry at a cursory glance does have materials from the 1918 flu,” he says. “It’s in the archive but there’s not a regional perspective on communities of color, no entry point for viewing that history from their perspective.” So knowing that we’re about to have another pandemic whose unfolding will be archived, Boyd-Pates was clear on the need to build that perspective into this initiative from the start.

“Then Black Lives Matter took center stage during the protests,” he says, “and I knew we needed to go all in on this direction.” The project immediately expanded to include the chronicling of not only the pandemic experience, but as well, the new civil rights movement. “It’s a vast opportunity to center those groups in a way that wasn’t done before,” he says. And this is especially urgent considering the disparate impact of the pandemic, on both public health and economic terms, on communities of color. Then when the BLM demonstrations get factored into the conversation, it’s clear that people of color are on the frontlines of both pandemic and political changes.

Images from the Los Angeles Black Lives Matter protests following the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, and Ahmaud Arbery. Images by Rob Liggins in Hollywood (Courtesy of the Autry)

Looking for photographic and oral histories as well as journalism and community organizing, Boyd-Pates has helmed active and specific outreach, resulting in hundreds of submissions received already, which so far do reflect that desired diversity. “We need to create a coherent story that includes it all,” Boyd-Pates says. “The beauty of this moment is that it’s not monolithic, technology and etc. allows for more intersectionality and real-time global engagement that informs the curation.”

This level of community involvement clarifies aspects of the narrative in ways that make sure oversights are not codified into the archives, and ensuring that future curators and historians will not have to do the work of recentering in which Boyd-Pates is immersed with regards to the past. In this way, both his original mandate and the emergence of a modern-day parallel can be seen as facets of the same calling. From the classroom to CAAM to the Autry, for Boyd-Pates it’s all a question of direct engagement with the throughlines of democracy and access.

Tori Tingley Ryan (CCHI at the Autry Collection)

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.