Quilts are supposed to be comforting, even nostalgic. It’s a warm, folksy art form and a universally practiced and revered craft, which even at its most sophisticated evokes childhood bedrooms, hope chests and grandmothers. That softness is one big reason why, in the hands of an artist and author like Christopher Myers, textile can be such a powerful idiom through which to chronicle more challenging personal and historical narratives. The juxtaposition of tradition and revision that occurs when a colorful, expertly sewn, large-scale “quilt” depicts, for example, Confederate monuments, iconography of slavery, police violence or the climate crisis, is powerfully affecting, with a dissonant charm and an intuitive understanding that these thing too are part of the story of our family.

Christopher Myers at Fort Gansevoort

Myers is also a consummate traveler and an acclaimed playwright, for whom fluid concepts slip between the realms of language and images in synchronistic, suggestive ways. Ideas about authorship, collaboration, cross-cultural pollination, intergenerational storytelling, mythology, literature and the oral histories of displaced communities all converge in his literal and metaphorical patchwork tableaux. The contradictory vectors of freedom and bondage represented in the colonial and diasporic forces of history find their layered analogies in these monumental tapestries, whose sharp, emotional and sometimes dark parables express it all in bright, jubilant patterns and saturated colors. Each one contains hundreds of individual pieces of textile, but all the more do they contain thousands of pieces of history.

In what is a cornerstone work in the exhibition, “What Does It Mean To Matter (Community Autopsy),” Myers creates a group portrait of several of the many, too many, victims of police violence whose deaths sparked the Black Lives Matter movement. Each figure is embellished only with the embroidered representations of the bullet wounds that killed them. These chalk-outline style figures are rendered in solid, darker skin-tone fabrics, the half dozen or so background panels in varied but understated traditional patterns. By comparison to the often vibrant, florid, even tumultuous colors and densely detailed settings and scenarios in other works, this piece is contemplative, even somber. It shows violence, but is not itself violent. It is still a lovingly assembled quilt, and that’s the quiet magic of this work.

Christopher Myers, How to Name a Famine, a Fire, a Flood? (Fort Gansevoort)

In the rather epic “How to Name a Famine, a Fire, a Flood,” Myers directly addresses global headlines about the climate crisis in a fairly literal tableaux illustrating the title. But his expert conjuring of precise landscapes, pictorial space with Grant Wood-inspired depth of agrarian rolling-hill perspectives and deftly rendered figures make the deeper message more explicit still. The looming climate crisis affects us all, but the poor and communities of color can be expected to bear the brunt of the disasters, earlier and more devastatingly than the privileged. For Myers this is more than academic or theoretical. He has traveled and worked all around the globe, maintaining a storytelling practice and a growing international family of artisans and collaborators, from whom he learns in an unceasing curiosity for stories, histories, experiences, techniques and enriching perspectives.

Christopher Myers, Every Temporary Hero (Fort Gansevoort)

Several of these perspectives combine in works like “Every Temporary Hero” in which Myers treats the archetypal revolutionary act — the tearing down of oppression’s monuments and statues — in a geopolitical continuum from Lenin to Saddam the American Confederacy. This work is quite schematic and almost abstract; it’s a shadowy tumult wherein even if you don’t recognize each individual toppling figure you still feel the heft of the patriarchy they contain as they fall. It’s an action with a sense of philosophy and momentum, but also a reminder that we have been here before, for better or worse, that no moment is an island in the stream of history.

While the exhibition takes its title, Drapetomania, from an offensive and obviously debunked 19th-century pseudoscientific theory that posited slaves’ impulse to flee as a mental illness, the show’s most massive and architectural work, “The Talented Tenth and the Beauty of Existence” also takes science as a starting point. Data science to be precise, developed by W.E.B. Du Bois in 1900, and meant to account for accomplishment and beauty even amid global upheaval.

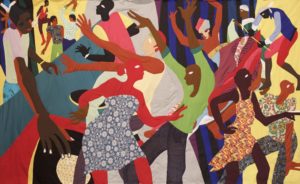

Christopher Myers, I Insisted that Our Movement Not be Turned into a Cloister, 2019, 96 x 168 inches (Courtesy of Fort Gansevoort)

There are also a number of sculptures in the exhibition inspired by the same esoteric convergence of ideas, but employing both materials and imagery specific to the slave trade and other kinds of potentially less sinister encounters between the black body and commerce across related areas of autonomy and agency. For example, a gold filigree face cage called “A Doubling of Cages” is made in honor of “an unnamed African-American sideshow geek in a WPA photograph” and Myers speaks movingly about that while the idea of men in cages is abhorrent, this performer found a way to make a living for himself, a free man on stage, and that way, the cage can also represent the shadow of true freedom.

A majestic chandelier collar lit up with candles, “Shackle and Light” transforms an onerous trap into a veritable supernova of flickering hope. Lit by the artist before the opening in a ritualistic, hopeful convocation pairing the warmth of candlelight with the unbearable burden of the steel was a fitting inaugural for the show, the first in this New York gallery’s L.A. space. And importantly, befittingly, and in keeping with the layered experiences of the quilts, this performative sculptural illumination was also an act of remembrance, spirit, and the communion of souls.

The exhibition is on view at Fort Gansevoort, 4859 Fountain Ave., East Hollywood, through Saturday, February 8. fortgansevoort.com.

Christopher Myers at Fort Gansevoort

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.