Movie theaters are still closed in the movie capital of the world. While AMC, Regal, Century, and other major theater chains in Orange County have been liberated to screen Tenet, Los Angeles is still stuck in Governor Newsom’s dreaded purple tier, indicating widespread COVID-19 transmission. Until that color turns red, theaters in the county are prohibited from indoor operations. Among the most vulnerable of these are the art house spaces. Supplying the local cinephile community with a variety of indies, foreign titles, and retrospectives of all kinds, they are struggling under the weight of the pandemic, but they are hanging on. Here, we take a look at L.A.’s art house movie business and what owners are doing to survive and keep movie magic alive.

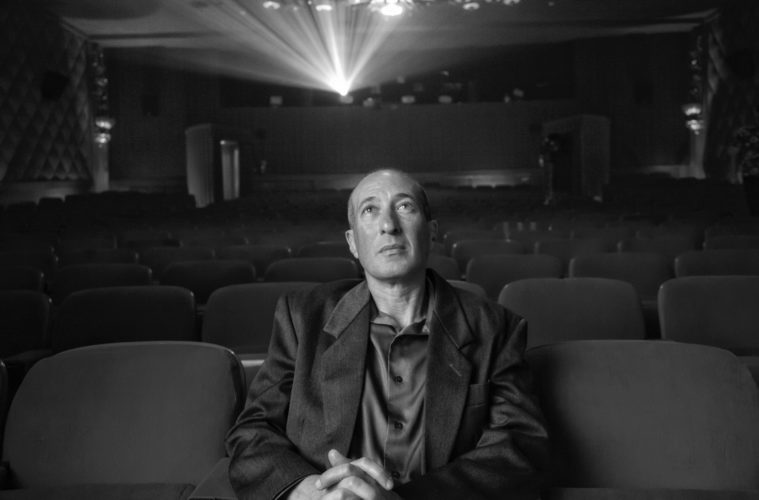

Christian Meoli (Courtesy Arena Cinelounge)

Arena Cinelounge

You may have heard of Christian Meoli, who owns and programs the Arena Cinelounge, the slick 48-seater located on Sunset Blvd. just a few blocks west of the iconic Cinerama Dome. The Cinelounge was to be the first physical movie theater to reopen in L.A. since the initial lockdown. One of the most eclectic avenues for independent cinema in town, the single-screen art house regularly exhibited 4-6 movies per week, and on June 19 was slated to release festival darling Babyteeth along with a sparkling 4K restoration of Philip Kaufman’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being. “We sold out for the opening weekend,” Meoli remembers. Then, the evening before the relaunch, the news came down from the National Association of Theater Owners: movie theaters must remain closed. Local health officials confirmed this in short order. Meoli was disappointed but not defeated. His first thought: “Can we do a drive-in?”

Arena’s 23-foot screen has been dark for more than six months. The theater received some financial relief through the Art House America grant campaign, a fundraising effort administered by the Art House Convergence nonprofit. Meoli, a shrewd and tireless entrepreneur, has kept a modest revenue stream flowing through the theater’s gourmet popcorn line. With names like “Natural Corn Killers” and “Truffaut Truffle,” each delicious, non-GMO bag is available for home delivery. But these signature concessions are no bulwark against the ticket revenue shortfall. When the county jumps a tier, Meoli will be ready with air purifiers, disinfectant, and socially distant seating. “We feel like we can open,” Meoli muses. “People want to come back to the movies.”

(Courtesy Laemmle Theatres)

Laemmle Theatres

Greg Laemmle is CEO of Laemmle Theatres, the family-owned establishment with roots dating back to the beginnings of the movie industry. Founded in 1938 by the nephews of Carl Laemmle — the legendary mogul and founder of Universal Pictures — the theater chain operates seven locations throughout Los Angeles County, with an eighth finishing final inspection in Newhall. Laemmle’s wife was hanging art in the unopened theater while COVID cases surged.

A staple of L.A. moviegoing culture, the Laemmle name is synonymous with the discovery of new and classic cinema. The recently refurbished Monica Film Center, a block south of the bustling Third Street Promenade, is the company’s longest continuing operating theater. Their Pasadena Playhouse 7 theater boasts the largest seating capacity at 250, but the business strategy lately has been to embrace smaller auditoriums reminiscent of studio screening rooms. Whether roomy or cramped, the compartments have been vacant since that fateful week in March when the coronavirus outbreak was declared a national emergency.

Greg Laemmle, who runs the chain with his father Robert, is wise and practical as he takes stock of the sobering state of affairs. “As we were shutting down we had some confidence that our employees would be taken care of,” Greg Laemmle observed. “Now that’s less certain.” The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), a loan that incentivizes small businesses to keep their workers on the payroll, doesn’t deal with businesses that have shut down. “You need to be open to take advantage of that,” Laemmle says.

The Laemmle brand has continued to attract the masses through a variety of virtual offerings. Almost immediately after the doors were shut and locked, the company inked a deal to release titles through Kino Marquee, Kino Lorber’s virtual theatrical exhibition initiative. One of the first movies released under this model was Bacurau, the stylish Brazilian thriller which took home a Cannes jury prize last year.

“Virtual cinema is not a replacement for us in exhibition or for the small distributors that are in business with us,” said Laemmle. “Replacement VOD has not been a success for studios, either. When you look at the overall revenue there’s a giant hole. That’s theatrical revenue.”

The Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) program, designed by the U.S. Small Business Administration to assist with utilities and rent, didn’t even cover a month of rent for the seven theater locations. “We were putting all our eggs in that basket,” Laemmle explained. “But we have a plan that we think will get us through.”

In the meantime, all of Laemmle’s venues, including the Laemmle Royal on Santa Monica Blvd., with its English club room ambience and decades’ worth of accumulated memorabilia lining the lobby walls, will remain closed to the public.

(Courtesy Egyptian Theatre)

The American Cinematheque

The American Cinematheque, the indispensable year-round film festival with locations at the Egyptian Theatre on Hollywood Blvd. and the Aero Theatre in Santa Monica, is in a slightly more advantageous position than its small-business counterparts. In May, Netflix finalized a deal to purchase the historic Egyptian, whose handsomely appointed halls first opened in 1922 at the height of silent-era glamor. “There’s no way we would have survived the first week of the pandemic,” says Gwen Deglise, head programmer at the Cinematheque. “There are not many nonprofit art houses that can survive without revenue for six months. We’ve been able to retain a lot of our team. We have stayed focused.”

Like many other nonprofits, the Cinematheque reinvented itself during the health crisis. When COVID threw the population into peak panic mode, they were in the middle of one of their signature annual events, Noir City: Hollywood, a classic crime film retrospective co-presented by the Film Noir Foundation.

To keep their member-based community engrossed, the organization pivoted to virtual screening engagements, premiering a rare Agnes Varda short, The Little Story of Gwen from French Brittany, and Peter Sellers’s long-lost 1961 directorial debut, Mr. Topaze. A seed grant from the Hollywood Foreign Press Association allowed them to digitize Q&As from their analog archive. In the wake of the George Floyd protests, a genteel Barry Jenkins appeared on Zoom to interview an energized Spike Lee about his new Netflix film, Da 5 Bloods. Werner Herzog, Miranda July, and Jude Law subsequently made memorable virtual appearances.

In June, the Cinematheque forged an ingenious partnership with the Mission Tiki Drive-In in Montclair for a series of retro double features, allowing them to salvage what would have surely been a lost summer. Beyond Fest, a roving series co-founded by American Cinematheque programmer Grant Moninger, launches on October 2 at the new drive-in residence. (Read more here).

Although these crisis-averting strategies have kept Cinematheque members fed, they have not replaced the sense of belonging one immediately feels when crossing the lavishly carpeted foyer of the Lloyd E. Rigler Theatre at the Egyptian. The lack of a communal experience, powered by living bodies in a shared space, is still keenly felt. “What drives me is the connection between the film, the filmmaker and the audience,” says Deglise. “Someone has poured their passion into this film. Here’s the audience to discuss it. It has found its home.”

UCLA Film Programmers Paul Malcolm and KJ Relth (Photo by Jennifer Rhee)

UCLA Film & Television Archive

The Billy Wilder Theater has stood silent since March 8. The last film to screen there was Better Luck Tomorrow — a 35mm print, to be precise, on loan from the DGA to mark the 50th anniversary of the UCLA Asian American Study Center. Now the pink vinyl seats lining the stadium are vacant, its proscenium stage deserted. Located in the Hammer Museum in Westwood, the Billy Wilder is the official venue for the UCLA Film & Television Archive, the visual arts nonprofit with a collection second only in size to the Library of Congress.

For quarantine season, the Archive initiated a “Safer at Home Cinema” in which staff members offer diverse streaming recommendations. Notable virtual events included a new restoration of Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó (co-presented with Arbelos Films) and Women to the Polls, a festival celebrating the centennial of the passage of the 19th Amendment. The latter was originally scheduled to play in-person but was cancelled after opening night in response to the spread of coronavirus.

The Archive applied for a $300,000 emergency relief grant through the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) under the new CARES Act program, but did not receive it. The effort wasn’t wasted. “The proposal allowed us to build a comprehensive plan for what the virtual screening series would look like,” explains KJ Relth, one of the Archive’s chief programmers.

Backed by the mighty University of California system, the staff has kept busy. “We’re focusing on getting things from our collection that we own the rights to, or items where we have a strong relationship with the independent artist who owns them,” said Relth. Programmer Paul Malcolm was also impressed by the collaborations that have been forged during the lockdown. The Chicago Film Archive partnered with UCLA to release the recently preserved The Murder of Fred Hampton, a feature-length documentary about the last nine months in the life of the Black Panther Party leader. “That’s the kind of collaboration we weren’t able to do before,” Malcolm said.

The UCLA Film & Television Archive’s deep collaboration with their preservation team continues despite the extended theater closures. “We’ve already looked at lists to identify prints that have not played in our theater during the last five years, or have been prepped for other theaters,” Relth said. “We’re putting together a Back in Business program, essentially a greatest hits program of everything that’s been restored over the last decade. L.A. Rebellion stuff. Some key Robert Altman films.”

Films at UCLA (Photo by Juan Tallo)

What’s Next?

If theaters reopen in L.A., are people going to come back in significant numbers? The question hangs in the air like a bilious smoke cloud. The film-going community has undoubtedly formed new habits during the dramatic paradigm shift of the last six months. Drive-ins and streaming have become more prevalent and with more choices for in-home viewing than at any other time in history, the desire to participate in society has, for many, slowly drained away. Why go out when only Disney+ has Hamilton or Apple TV has Greyhound?

One key ingredient that’s lacking in many streaming platforms — The Criterion Channel respectfully excluded — is a sense of intelligence behind the programming. “The big problem is that nobody knows what to watch,” says Meoli. “Watching movies at home is a search-driven process, not a discovery-driven one. We offer personalization. That is the essence of arthouse cinema.”

“We make it a little easier to find content that’s of value,” adds Laemmle. When late last fall the Laemmle Royal premiered Rialto’s new 4K restoration of Joseph Losey’s classic paranoid thriller, Mr. Klein, it stayed on for three weeks — highly unusual for a retrospective screening of that sort. “It was a perfect example of a film that demanded to be seen in theaters,” Laemmle said. (It should be noted that no one is currently streaming Mr. Klein.)

“We’re very industry-driven in L.A.,” says Deglise. “And that’s as it should be. We’re an industry town. But our film culture goes deeper than that. Our audience is contributing to the discussion of cinema. It’s as elevated as the discussions in Paris and New York. Virtual screenings should not be the only option. If we don’t connect in real life, we lose a part of our humanity.”

Relth is optimistic about the prospect of reopening. “Look at the dining trend emerging. There’s a huge desire to get out of the house and interact in the world again,” she insists “I just hope that we’re craving the excitement of social interaction so much that we can open safely. When we do, it will be a sweet reunion. A homecoming.”

THE STATE OF THE ARTHOUSE (This week’s L.A. Weekly cover story by Nathaniel Bell)

“It’s that aliveness,” says Malcolm. “You can’t pause it. It’s about surrender. You need to surrender yourself to something for a couple of hours. And that’s a commitment. That’s a position of vulnerability.”

Audiences must now weigh a desire for that lost communal experience against the fear of a contagious disease that doesn’t seem to be going away anytime soon. If theaters in L.A. reopen, they will do so only under a strict regimen of regular seat cleaning, recycled air, and other such protocols. This is true not only of the art houses here, but also the Nuart, the New Beverly, the Alamo Drafthouse, REDCAT, the Samuel Goldwyn, the Vista, the Los Feliz, the Fairfax, and all the other glorious spaces that comprise the film ecosystem in Los Angeles.

“We want to celebrate this idea of what movie theaters mean to us,” concludes Malcolm. “We’re here, we’re doing what we can, and we’ll be there for you when we’re allowed to come back.”

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.