In the midst of a pandemic, the city has its highest ever budget for homelessness and possibly its greatest opportunity to aid those in need.

Before the pandemic, it was not unusual to see homeless encampments along Los Angeles’ Skid Row, or be asked for money while enjoying a night out in the heart of downtown L.A.

The issue of homelessness has only compounded in a time where the country saw record unemployment, small business shutdowns and in some cases, a culture where people would rather live on the streets than be housed.

Homelessness has been an issue not just the city of Los Angeles, but also the county and state of California. In the historically large $100 billion state budget signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom earlier this year, $4.8 billion will be dedicated to homelessness.

On a local level, Mayor of Los Angeles Eric Garcetti dedicated $1 billion of the city’s budget to solving the homelessness crisis.

Homeless encampments are installed on an overpass of the CA-101 Hollywood freeway in Los Angeles Photo by Damian Dovarganes/AP/Shutterstock)

While the budgets are crucial to finding shelter for the homeless, the money from past measures may not have always been used in the most effective manner, according to a 2020 report by city controller Ron Galperin.

In the midst of a 2020 audit, before the pandemic, Galperin found that the homeless population had increased by 45% since 2016 when measure HHH was passed and the city of Los Angeles received $1.2 billion in general obligation bonds. With those funds, Los Angeles had planned to create 10,000 housing units, shelters, clinics and storage for the homeless.

In the report, Galperin criticized the measure’s progress, saying that the goal for building 10,000 units has amounted to 179 supportive units and 49 non-supportive units. He also projected that of the 5,522 supportive units and 1,557 non-supportive units in development, only 19% of them will reach completion by the start of 2022.

“Nearly four years have passed since voters approved Proposition HHH and despite the city’s efforts to lower costs and shorten timelines, the program’s current trajectory is increasingly falling short of the unhoused population’s needs,” Galperin wrote in his report.

The Los Angeles Housing Department refuted Galperin’s report, saying it fully expects to reach its goal of 10,000 units by the 10-year mark in the measure.

The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) estimated there were 66,000 homeless people in the city at the end of 2019. The 2020 homeless census was not taken because of the pandemic, so at a time when unemployment dropped to record lows and tenants got by with government rent freeze, it is unknown how much the homeless population moved in that time.

“The city’s never going to solve homelessness on its own,” Garcetti said back in September of 2020, adding that the response to the issue needs to be a nationwide one.

Where does that leave the homeless at this point in time? Garcetti and the L.A. City Council have pushed forward with multiple decisions that have affected the local homeless population this year, each one being criticized by homeless advocates.

In March, a planned closure of Echo Park Lake to repair more than $500,000 in damage led activists to protest over “sweeps” of the homeless community that resided there.

“Proposed sweeps of homeless encampments don’t resolve the issue of homelessness,” Cassie Flower, who attended the Echo Park protest, said to L.A. Weekly. “We need to be supporting those who need it, not shoving them in a dark corner. The Echo Park encampments have built a loving community at the lake, a safe haven where they can build trust and safety with one another and have a sense of stability. Why would we take that away, especially during a pandemic?”

The sentiment was that the homeless population was being purposely displaced, although Councilman Mitch O’Farrell had promised that every single homeless person in the Echo Park Lake community would have the opportunity to be housed in hotels, although homeless advocates said the living conditions in those hotels were “prison-like.”

Another city ordinance that has left the homeless in a vulnerable position came about at the end of July, with what has been colloquially known as the “homeless encampment ban.”

In a 13-2 vote, the L.A. City Council approved an ordinance that could potentially ban encampments and sleeping near schools, parks, bridges and overpasses.

A homeless man sleeps on the beach before City of Los Angeles sanitation workers showed up to clear homeless encampments in Venice on July 30, 2021. (Photo by Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times/Shutterstock)

Part of the order states it would ban any person from sleeping, sitting, lying, placing or storing personal property in the “public right-of-way,” or block sidewalks in a way that would interfere with the Americans Disability Act.

“If we all agree that the status quo is unsustainable, that street encampments are dangerous to both the housed and unhoused, why would we continue to allow them anywhere, if an alternative exists, like in my district today,” Councilman Joe Buscaino said while addressing the ordinance Wednesday. “It’s an improvement from what we have today.”

Protesters rallied against the ordinance in downtown L.A., holding signs that read “Services, not sweeps,” and “Poverty is not a crime.”

Buscaino then doubled down on the ordinance, almost immediately proposing that the ban apply near schools.

“I do not plan to stop at just schools,” Buscaino said in an August 16 press conference. “I plan to designate such ‘anti-camping’ zones around other sites like beaches and parks.”

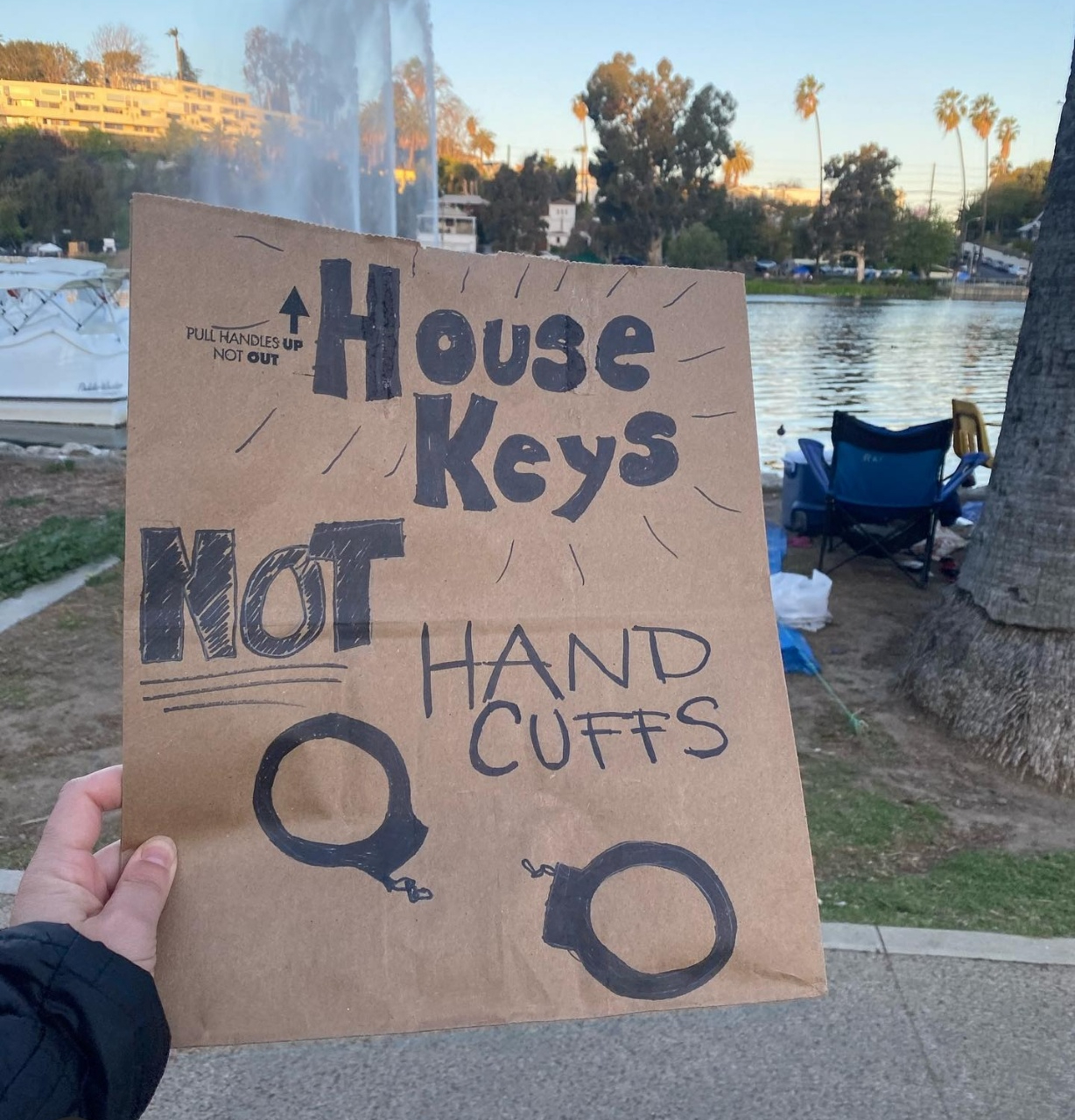

Protesters huddled within inches of Buscaino as he spoke, holding signs that read “house keys not handcuffs,” which they also chanted, often drowning out Buscaino.

“This is evil. Pure and simple,” homeless advocate Theo Henderson said of Buscaino’s resolution. “As a person with lived experience of being unhoused and knowing unhoused families, this will put many unhoused in the shadows.”

The two council members who voted against the ordinance were Mike Bonin, who represents the 11th district of L.A. and Nithya Raman, who represents District 4.

“People want housing, they do not want warehousing, they don’t want shelter,” Bonin said Wednesday. “LAHSA (Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority) said… we have shelter beds for 39% of the unsheltered population in Los Angeles County. What about the other 61%? Where can they go? Where can they sleep?”

At an August council meeting, Bonin further spoke on the issue, opening up about his own lived experience with homelessness.

“I can’t tell you how much turmoil there is in your heart when the sun is setting and you don’t know where you can sleep. I can’t adequately express the combination of shame and frustration and anger and desperation and confusion you feel in that moment,” Bonin said during the meeting. “Yes, we have more shelter beds, more interventions than ever before, but despite all that, we still do not have enough units, or enough beds and it has not been easy. When I go home tonight, no matter what else, I know where I can sleep. Everybody in Los Angeles deserves to know that.”

The homelessness issue is one that has existed for decades and L.A. County Sheriff Alex Villanueva believes it has only gotten worse as L.A. has become a “destination” for the homeless across the country. The sheriff also pointed out that several of the homeless people in tourist destinations, such as the Venice Boardwalk, are homeless by choice and choose to live on the road.

“What’s the No. 1 failure of local government, at the county and city level? Why every measure fails and we see the problem get bigger and bigger? Because the city and the county have decided that they will not regulate public space,” Villaneuva said in a June press conference relating to homelessness. “When you don’t regulate public space, it will be occupied by somebody, somewhere. Period.”

Villanueva decided to take the issue upon himself, interviewing more than 250 people from the homeless communities in Venice, Malibu and other Los Angeles beaches and finding pockets of out-of-towners who were “homeless on purpose” and decided they preferred to live in Los Angeles beach areas.

A worker with the St. Joseph Center talks with a homeless couple along Ocean Front Walk in Venice on July 7, 2021 (Photo by Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times/Shutterstock)

On multiple occasions, the Sheriff has been seen patrolling the beaches – clearing out encampments which he says have become fire hazards.

“We are working actively to clear out the encampments,” Villanueva said in a July 21 livestream. “They are a threat to be the flashpoint of a wildland fire where the urban interface with the wildland and the foothills… all that is high fire danger.”

The Sheriff has also been critical of the L.A. Board of Supervisors, urging them to declare a state of emergency on homelessness. Of late, the thought has been echoed by City Attorney Mike Feuer, who is making a run for mayor of Los Angeles.

“Our homelessness emergency is the result of an acute lack of affordable housing, joblessness, a failed mental health system, a system that fails our veterans, substance abuse, domestic abuse and many other factors,” Feuer said after a fatal September stabbing at the Veteran’s Row Homeless Encampment in West L.A. “It touches every neighborhood and degrades public safety and quality of life everywhere. We need a new law that enables us to say to people on the streets that we have a place for you to go for housing and services. But we also say to them that the streets, sidewalks and parks are nowhere for you to live. And, after a period of time, you can’t stay here. Our public spaces need to be safe and accessible for everyone.”

When trying to explain the source of the homeless issue, Mayor Garcetti has said, “It’s trauma, meets high rent.” Even in the midst of a pandemic, the city has a budget and resources like never before, but may soon lose its leader to help plot it all out.

The Los Angeles Mayor has been nominated by President Joe Biden as ambassador to India, a position that Garcetti said he would accept.

Should Garcetti leave before his term is up, he would leave a city with not only trauma from a global pandemic, but a city scrambling for rent relief, both issues that Garcetti himself believes are the root of the homelessness issue.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.