Ever since the body of Brian Jones was found at the bottom of his swimming pool at his Cotchford Farm home in Hartfield, England, on the night of July 3, 1969, the Rolling Stones guitarist’s death has been portrayed as a sort of a moralistic object lesson about the consequences of partying too much and other self-destructive behavior.

Even more nuanced friends, band members, fans and critics who have long recognized that Jones was mentally and physically broken — following the unethical collusion of the English tabloid press and the police, who orchestrated a series of dubious drug busts in the late ’60s in order to make an example out of Jones — have long believed that he was somehow culpable in his own death and should have done more to save himself.

But Rolling Stone: Life and Death of Brian Jones, a new documentary by Spanish director Danny Garcia, makes a case that Jones was actually murdered. The film receives its U.S. premiere on Sunday evening, January 12, at the Regent Theater in downtown Los Angeles. Rumors about foul play involving Jones’ death have circulated since the night he died, but the more credible hypotheses have often been overshadowed by ridiculous conspiracy theories.

“He’s like rock & roll’s JFK — one of them, anyway,” Garcia, 49, says by phone from Costa Brava in an interview.

In the film, Garcia addresses (and quickly debunks) theories that Jones was murdered by Allen Klein, the Stones’ ruthless and not-always-ethical manager at the time, or at the instruction of the band themselves (who seemingly had no practical motive to have Jones killed after firing him from the group a month before his death).

Garcia relies instead on research and discoveries made by British journalist Scott Jones (no relation to Brian), who engaged in an extensive investigation over the past decade, tracking down witnesses who were at Cotchford Farm and delving into police files at the National Archives of the U.K. Garcia’s film is hardly definitive, as it basically rehashes the work of Scott Jones and various reports in the British press about his findings that came out years ago. Several other films about Brian Jones’ life are reportedly in the works, but Garcia’s low-budget film bears the distinction, at least, of being the first documentary to get released, after its world premiere in London in December.

The director (who previously directed documentaries about Johnny Thunders, The Clash, Stiv Bators, and Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen) also draws heavily from the publication of two books about Jones’ death, Geoffrey Giuliano’s Paint It Black: The Murder of Brian Jones (1994) and Terry Rawlings’ Brian Jones: Who Killed Christopher Robin?: The Truth Behind the Murder of a Rolling Stone (2004). The screening at the Regent Theater will be the second time that Rolling Stone: Life and Death of Brian Jones has been shown. The film’s wider release should go a long way toward rehabilitating Jones’ reputation as a self-destructive fuckup who fell on his sword as some sort of rock & roll martyr.

“I’ve been a fan of the Stones since I was 6 years old,” Garcia says. “My favorite album was Aftermath. This has been a lifetime of studying the case. Brian was not only the guy who started the band, he was the guy who was more interesting, to me anyway.”

Jones was “the first English rock star,” British journalist Chris Salewicz declares early on in the documentary. As the founder of The Rolling Stones, as well as the man who named the group, Jones was far more strikingly fashionable in the early days than his relatively dorky bandmates. Garcia gathers a loose assortment of Jones’ friends, acquaintances, lovers, relatives, and second-tier musical peers — actor-model Zouzou, Stones tour manager Sam Cutler, Jones’ daughter Barbara Anna Marion, English rock singer Chris Farlowe, photographer Gered Mankowitz, Jones’ friend Prince Stash Klossowski de Rola, and The Pretty Things’ Phil May and Dick Taylor — alongside various writers and observers, including Scott Jones, Keith Altham, Simon Wells, Graham Ride and Salewicz, among others. Some of their insights are illuminating, but, as with Garcia’s previous and often-slapdash rock documentaries, the lack of participation by, and access to, crucial people in the subject’s life is a significant problem.

“We’ve had a lot of help from people around Brian, even fans who had photos of Brian,” Garcia says. “It’s about time we show Brian in a different light.”

The film also includes archival audio clips about Brian from the late Stones keyboardist/tour manager Ian Stewart and Jones’ straitlaced father, Lewis Jones, who was dismayed that his precociously talented son rejected his classical-music training to pursue jazz and rock & roll. Garcia traces the arc of Jones’ life from his childhood in Cheltenham, where he was coldly shunned by his parents after his sister Pamela died of leukemia at a young age, to his time in London, where he first drew attention as a blues fanatic and slide-guitar phenom (a rarity in England at the time) who eventually fell in with a group of like-minded allies he named The Rolling Stones, after the Muddy Waters song “Rollin’ Stone.”

But Jones was eventually supplanted as the group’s leader when bands of the early-’60s British Invasion began writing their own songs. Like The Beatles and The Kinks, the Stones started out primarily doing blues covers. But as singer Mick Jagger and guitarist Keith Richards developed the knack for penning their own tunes, Jones’ role changed. Even as Jagger and Richards inevitably drew more attention, Jones continued through the mid-’60s as the group’s most distinctive and versatile musician and arranger.

The Rolling Stones at Kungliga Tennishallen in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1966 (courtesy of Chip Baker Films)

“Brian couldn’t write songs himself,” says Jones’ friend Prince Stash Klossowski de Rola, in a phone interview with the Weekly from his home in Malibu. “He was too much of a perfectionist. He had too much self-doubt … But he was very much the alchemist who transmuted the Stones’ early songs. I was with him in the studio when he did ‘Ruby Tuesday’ … Because of his contributions [as a multi-instrumentalist], Brian was able to take charge in the studio. He was authoritative,” Stash adds.

“He was so inventive and so brilliant and had such perfect touch,” Stash continues, praising Jones’ depth and musicality. “His contributions made all those songs — ‘Paint It Black,’ ‘Under My Thumb,’ ‘Ruby Tuesday.’ He had an extra ability to make it happen … He was not just a blues purist. He and I worked on avant-garde material … Unfortunately, I’ve been looking forever for the tapes. We did a lot of stuff that was very interesting, and Brian came up with all this inventive music which drew inspiration from Indonesian music to Turkish classical music.”

But Jones’ musical abilities and health became seriously compromised when he was targeted by London police and set up by writers at the conservative British tabloid The News of the World in a campaign that involved harassment, spying, planted evidence and multiple arrests. One of the reasons Jones relocated in November 1968 from London to Cotchford Farm, in the village of Hartfield in rural East Sussex in southern England, was to escape the relentless scrutiny and entrapments. The bulk of Garcia’s documentary examines those final months at Cotchford and the possible reasons why Jones was killed.

It now appears that Jones might have died for no other reason than that he was embroiled in a dispute with construction worker Frank Thorogood, in a bizarre, tragic and real-life version of the 1986 film The Money Pit. Thorogood was the leader of a group of sketchy builders who had been hired by Jones to renovate Cotchford Farm, the idyllic home that had been formerly owned by Winnie-the-Pooh creator A.A. Milne. Instead of fixing the place, Thorogood and his crew moved in and took over Jones’ house. The day that Jones finally fired the construction workers was the same day he died, and Thorogood was initially detained by the Sussex police before being released.

“It’s pretty clear that this guy was involved, that guy and his buddies,” Garcia says. “These guys were using Cotchford as a party place, ripping off Brian for months.”

The film also points a finger at Tom Keylock, the Stones’ minder-driver-fixer who several people allege covered up Jones’ murder. Years later, Keylock claimed that Thorogood confessed to Jones’ murder on his deathbed, then said that the confession never happened. Both Thorogood and Keylock are now dead. What is known is that the married Thorogood had a girlfriend, Joan Fitzsimons, who sometimes stayed with him at Cotchford, and who was brutally attacked and left blinded just three weeks after Jones’ death — after expressing her fear of Thorogood to the Sussex police. Keylock was also married and having an affair with a nurse named Janet Lawson, who was the person who discovered Jones’ body in the pool. After the attack on Fitzsimons (who died in 2002), Lawson went into hiding and remained silent about the events at Cotchford until she was interviewed by Scott Jones in 2008, shortly before her own death, when she disavowed her earlier statements to the Sussex police and said that Thorogood had killed Jones in an act that “was probably the result of horseplay that had got out of hand.”

The film also raises the possibility that Jones was actually drowned in a small trough or pond next to the house before being moved to the swimming pool, according to interpretations of the coroner’s report, which found freshwater in Jones’ lungs instead of chlorinated pool water. “The neighbor was adamant that he was drowned in the trough, a small body of freshwater,” Garcia claims.

The account given to the Sussex police that there were only three other people — Thorogood, Lawson and Jones’ girlfriend Anna Wohlin — at Cotchford Farm on the night of the death is contradicted by information in the documentary that indicates that were several other people in the house that night, including the other construction workers and Jones’ ex-girlfriend Suki Poitier. One could also argue that Jones was virtually murdered a second time by the police —serious questions remain about whether the Sussex police were merely inept or had other motives when they failed to follow up on the leads they were given by witnesses.

“You can tell there’s a lot of dodgy stuff,” Garcia says. “That’s why Barbara [Brian’s daughter] says it was a completely bungled investigation,” he adds referring to a moment in the film when Barbara Anna Marion wonders why the Sussex police didn’t investigate her father’s death more thoroughly. “They were so clumsy, they left this paper trail behind.”

Given the startling information in the books and film, Garcia was asked if there was any reaction from the other members of The Rolling Stones following the documentary’s premiere in London in December. “So far, nothing,” he says, adding that he’s not especially surprised that the Stones have kept their distance from the controversy surrounding Jones’ death. “It’s not about The Rolling Stones, per se … The Stones come out really well [in the film].”

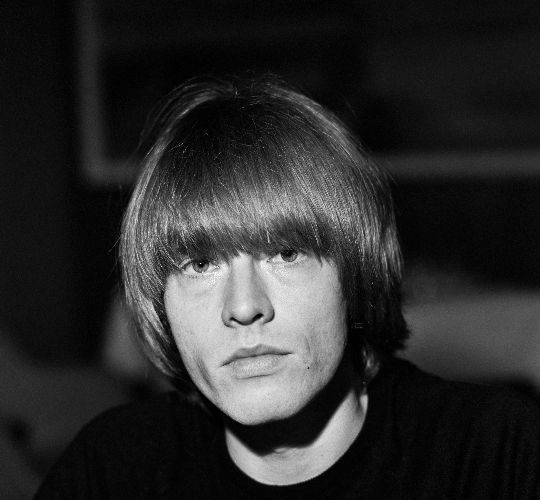

Brian Jones in 1967 (photo by Ben Merk Anefo)

Among the documentary’s major drawbacks is that Garcia was unable to get permission to use any of Jones’ or the Stones’ music. “ABKCO [which holds the rights to the Jones-era Stones recordings] didn’t really respond to our emails,” he says. Instead, he assembled a soundtrack of songs by musicians who sound like the Stones, including contributions from The Only Ones’ John Perry, The Chesterfield Kings’ Greg Prevost, and Alabama 3 (whose harmonica player, Nick Reynolds, co-wrote the film with Garcia). “What we needed is music that fits the bill,” Garcia insists. “We had Dick Taylor [a member of the original Stones lineup who went on to play with The Pretty Things] record two songs specifically for the movie … We ended up with a pretty cool soundtrack.”

Did the filmmaker try to interview the various members of The Rolling Stones about Jones? “We approached everybody,” Garcia answers but says he had no success getting them to talk. What about such people as Bill Wyman and Marianne Faithfull, two disaffected figures who are no longer part of the Stones camp? “Bill is doing his own documentary and didn’t want to get involved in this one.” As for Faithfull, he says, “She doesn’t want to talk to anybody about the Stones.”

Of all the people who do appear in the film, it’s Prince Stash Klossowski de Rola who best gives an impression of what Brian Jones was really like, apart from the details of his tragic death and the several decades of mythmaking about his self-destructive tendencies. “He’s like the keeper of the torch,” Garcia marvels about Stash. “He loves Brian in every way. He was fucking there. He got arrested with Brian — you don’t get any closer to Brian than that.”

“We were rebels. We were outcasts in a defiant way,” says Stash, who will take part in a Q&A at the film’s Los Angeles premiere on Sunday. “There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t in some way think of Brian. I have a connection to Brian because of the music, a great inspiration in the true sense of the word. We pioneered with our bizarre accouterments the way people can do and look anyway they want. It was hard to survive in the 1960s the way we looked. We were attacked by our own families … His own attorneys thought he was guilty. In those days, it was a class thing. They hated The Rolling Stones. They didn’t like that we were long-haired louts,” he says about the time Jones pled guilty to a drug charge even though he was innocent. Why would Jones do such a thing? “He thought he could atone in the eyes of his parents or something,” Stash muses.

Stash, 77, grows more reflective as he looks back on all the time that has passed. “I’m getting on it, as it were. So many friends have popped off left and right. As you get older, there’s fewer and fewer of the old friends left alive … I am determined to fight so many of the hideous urban legends about my friend,” he continues, referring in part to “that fairly ghastly film,” Stoned, director Stephen Woolley’s fictionalized 2005 drama about Jones. “It’s a bit of a cause for me. After I’m gone, there’ll be distortion.”

Stash, who was a major contributor to Michael Cooper’s recent photo book, Brian Jones: Butterfly in the Park, was more than just an occasional musical collaborator for Jones. “I was a rock star in my own right with Vince Taylor,” he says about his days playing with the influential but now overlooked late-’50s English rock singer. “I knew Anita [Pallenberg] very well. Anita was my girlfriend before she met Brian … She met the Stones through me,” when the Stones and Vince Taylor were billed together for several shows at the Olympia in Paris on Easter weekend in 1965.

“The circumstances of poor Brian’s death are shrouded in a kind of very sordid affair,” recalls Stash, who was in Rome when Jones died. He was saddened further when another good friend, actor Sharon Tate, was murdered just a month later. “It was a very odd and traumatic event. It was all due to those sinister louts, Thorogood and the builders. They were nasty pieces of work. They obviously resented Brian having all these advantages. [But] it was more manslaughter than murder,” he opines.

When did Stash first realize that Jones might have been murdered? “Relatively recently,” he says. “Within the last three years, I looked into it.” He describes the theory that The Rolling Stones benefited from Jones’ death as “absurd.” Does Stash believe Keylock’s claim that Thorogood confessed to him that he murdered Jones? “It’s not impossible. It sounds a bit self-serving. Your guess is as good as mine,” he answers. “Keylock was a weird person. He was not an unintelligent person. It seems bizarre. I know that Keylock made a sworn statement [about the confession]. He [Keylock] wasn’t the monster he was depicted to be. He was a very complicated personality. My theory is that he covered up due to this illicit relationship with his girlfriend [Lawson] … Keylock I knew very well. I can’t to this day see Keylock as the sinister figure they now paint him to be.”

With all the principal parties now dead, the idea of justice for Jones seems moot to Stash. “The great tragedy was the whole descent of Brian. It was very heartbreaking,” Stash says. “In 1969, Brian could no longer play.” There were occasional exceptions, such as Jones’ eloquent slide-guitar solo on “No Expectations,” but, in Stash’s mind, Jones “had a dying flame … Brian was the one who grew increasingly distrustful. He would say, ‘I think they’re too strong for us, the Establishment.’ … It’s very unfortunate that Brian succumbed.”

Stash worries that the film, with its focus on his death, might only give a negative impression about Jones’ life. He rails against previous portrayals “that painted my friend as a pathetic victim. He did tend to be arrogant in his demeanor. But he was a real star.”

Rolling Stone: Life and Death of Brian Jones screens at the Regent Theater, 448 S. Main St., downtown; Sun., Jan. 12, 8 p.m.; $15; ages 18 & over. (323) 284-5727, spacelandpresents.com.

Article was updated at 2:57 p.m. on January 12, 2020.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.