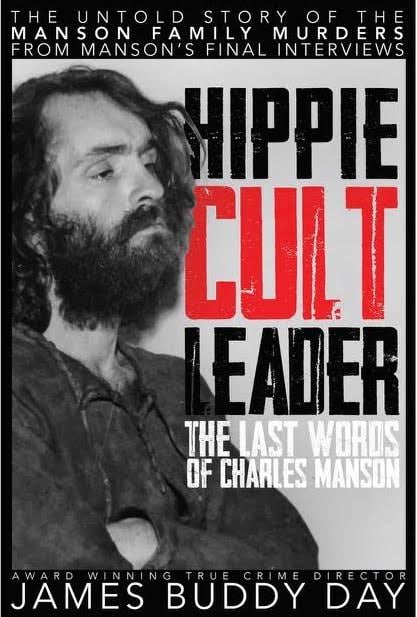

This Friday, August 8, 2019 marks the 50th anniversary of the Manson family murders, tragic events that for many in L.A. and beyond, marked the end of the peace and love era. Though Manson is not a figure to be revered or romanticized, he remains a source of fascination even in death and to this day. In a new book featuring his final interviews, Hippie Cult Leader: The Last Words of Charles Manson by filmmaker and author James Buddy Day, the infamous convict shares thoughts on the killing of Sharon Tate, the subsequent trial and his murderous followers.

During the final year of his life, Day interviewed Manson by phone from his cell in California State Prison, and he was the last documentarian to have access. The recordings laid the groundwork for Day’s documentary Charles Manson: The Final Words on REELZ Channel and now the book. Here, the author shares the bulk of Chapter one, recalling his first conversations with the cult leader.

——

“You eat meat with your teeth and you kill things that are better than you are, and in the same respect you say how ‘bad,’ and even ‘killers’ that your children are. You made your children what they are. I am just a reflection of every one of you.”

– Charles Manson, November 20, 1970, addressing the court outside the presence of the jury.

Charles Manson died on Nov 19, 2017. At the time, he was still an inmate in the custody of the California Department of Corrections, though his passing completed his life sentence. Before his death he was transferred from California State Prison in Corcoran California, to Bakersfield Hospital where he took his last breath on a Sunday evening, dying from complications associated with cancer.

Early the next morning my phone lit up with text messages. Still groggy I rolled over, reading the messages popping up and deciphering that Manson had died. I quickly got out of bed and made my way to work, attempting to respond to whatever I could. I listened to the news recount Manson’s life and speculate over the circumstances of his death, knowing that I had a long day in front of me. What the media didn’t know was that I had been working with Charles Manson on a documentary during what turned out to be the last year of his life.

The first time I spoke to Charles Manson was a Monday night. I was in Florida, filming a TV show called The Shocking Truth for REELZChannel (a true crime series about famous movies and the murders that inspired them). The cinematographer, Nate Harper, and I were in the midst of driving across the state retracing the footsteps of the female serial killer Aileen Wuornos, seeking out people who knew her.

“Holy shit,” I said to Nate, “I think Charles Manson is actually calling me on my cell.” My hands trembling from a rush of excitement, I managed to accept the call, and we both ran outside. The waitress— catching our escape from the corner of her eye—ran from behind the bar believing we were running out on our tab. Nate met her at the door and hurriedly gave her his wallet as collateral saying, “Sorry, we’ll be right back. Charles Manson is calling my friend and he has to take it.”

As we ran to the parking lot a second recording clicked in saying, “This call and your phone number are being monitored and recorded.” To this day I’m not sure if that means all calls are reviewed, or someone is eavesdropping in real time—either way I’ve long since decided to disregard. At the time, my prison calls were coming from the most famous inmate in the United States, and the sheer number of calls going in and out of the prison combined with the bizarreness of Charles Manson’s speech must have caused the monitors to throw up their hands in frustration years before I met him.

Within a few seconds Manson’s distinct voice came over the line, “Hello.”

“Charlie?” I said.

Manson responded, “Hey man, how you doing?”

“Pretty good, you?” I said.

“Groovy man,” Charlie paused, “I got your letter.”

Months before Charlie called me for the first time, I had been

speaking with many people involved with or researching notorious crimes, and I had met a few who claimed they had actually spoken with the infamous Charles Manson at one time or another. One person suggested that I write him, so on whim I sent him a couple of letters.

In the letters, I explained that I was a documentary producer, and I wanted to know if he would consider being interviewed for an in-depth documentary. I included my personal phone number and was fairly certain that he would never call. At the time it didn’t occur to me that handing out my cellphone number to the most infamous convicted mass murderer of all time might be unwise. When Manson called me that first time, I was shocked.

The inmate phone system only allows calls to be fifteen minutes or less. That, combined with the demand to use the phone and the prison- restricted phone time, makes connecting with outsiders challenging. When Charlie initiated a call, it came collect. Both my phone and I are from Canada, which at the time meant I had to set up a prepaid account to receive Charlie’s calls.

On that very first phone call, I could only speak with Charlie for a few minutes—just long enough to get the basic instructions on how to set up my phone to receive his calls. This proved difficult and resulted in numerous calls with the customer service desk, e-mails back and forth to get the complex instructions, and ultimately driving around the state of Florida to find a specific type of Western Union that would process the required money transfer to set up my account. After several days, I managed to get a confirmation e-mail while I was in northern Florida. We finished filming for the day and drove ten miles to the nearest post office, which was a one-room building on a rural road between counties. I used some hotel stationery and wrote out a quick letter to let Charlie know my phone was good to go. I wondered if the one time Charles Manson called me would just turn out to be a story I could tell at parties.

I remember reading Helter Skelter when I was a teenager, the bestselling true crime book of all time and the bible in terms of all things Charles Manson. My mother was an aspiring author and true crime fanatic, so we had a house full of books about murder, and I took to them immediately. Throughout my formative years I would spend my time on the bus commuting to school devouring books about kidnapping, homicides, massacres, and above all else, serial killers. My interest in serial killers blossomed as I grew older, and I read everything I could get my hands on. I went so far as to write a letter to the Milwaukee police department and request a copy of Jeffery Dahmer’s confession for a term paper. I recall paying a menial processing fee of ten dollars and receiving hundreds of photocopied pages in the mail, opening it like a Christmas present. This was long before the internet made such reading material readily available. I later pursued my interests in psychopathic violence academically, working on a post-graduate degree in counselling psychology.

As an adult, my fascination with crime evolved into a career as a documentary producer and director. I’ve had the unique opportunity to travel across America more than a few times curating stories about disturbing cases. I’ve met victims, attorneys, inmates, and everyone in between. I’ve heard some incredible accounts and met some really bad people. Through all the years of preoccupation with real-life monsters, one particular fiend always stuck with me: Charles Manson, the charismatic psychopath who, as legend has it, turned Sunday school teachers and librarians into bloodthirsty killers.

I was fascinated by the idea of the Manson Family, a sixties-era cult fuelled by sex and drugs in which the members would abandon their personalities and take nicknames like “Squeaky,” “Tex,” and “Lulu.” The idea that Charles Manson was an insatiable genius who could get into the minds of his followers and bend them to his will was haunting. Helter Skelter was written by Vincent Bugliosi, the Manson Family lead prosecutor, and told a bizarre story of sex, drugs, and an apocalyptic cult set against the backdrop of civil unrest in Los Angeles.

It was a great story.

About a month went by before Manson called me a second time. The automated voice came on the line first, “You have a pre-paid call from Charles Manson, an inmate at the California State Prison in Corcoran, California. To accept this call, say or dial 5 now—beep.”

I eagerly pressed 5 and heard his raspy voice say, “Hello, hello, hello.”

I was astonished Manson had taken the time to call me back. Why? What does he want? I thought. What do you say to the most infamous mass murderer of all time if given the chance? I knew what I wanted: to hear Manson’s story in his own words and to get his permission to make a documentary based on that story. Manson’s response was blunt, “I don’t give a fuck about telling my story. That’s not what’s in play here. My story has already been all over the world a thousand times. I’m interested in results. Can you get me a cellphone between you and I so we can communicate?”

I was astonished Manson had taken the time to call me back. Why? What does he want? I thought. What do you say to the most infamous mass murderer of all time if given the chance? I knew what I wanted: to hear Manson’s story in his own words and to get his permission to make a documentary based on that story. Manson’s response was blunt, “I don’t give a fuck about telling my story. That’s not what’s in play here. My story has already been all over the world a thousand times. I’m interested in results. Can you get me a cellphone between you and I so we can communicate?”

I knew enough to know that cellphones are not permitted in prison, and that our phone calls were ostensibly being monitored and recorded by prison officials. I was taken aback that Manson, who I barely knew, would ask me in no uncertain terms, on a recorded line, to commit what I assumed was a federal crime. I told him I didn’t think that was possible and even if it was, I had no idea how to do it.

“You’re the man-jam,” Manson said. “You’re the one that’s got the revolution money-bunny-back-door-rabbit-jack. In other words, I’m the one that’s locked up.” Manson’s point of view was that I could find a way to get him a cellphone—I was on the outside, where anything is possible. He was in prison so all he could do was ask.

I told Manson I didn’t want to join him in prison, so I wasn’t going to smuggle him in a cellphone, but he was undeterred.

“I can’t even get the chicken shit door open,” Manson said, offering me an ultimatum. “Give me a cellphone so I can communicate with the world. And get me a door, so I can get some air once more, or stay away from me!”

I pressed on, “Don’t you care about all the movies, books, and TV shows that have been made about you? Don’t you want to set the record straight?”

Manson was keenly aware of the decades of stories that had been told about him—he didn’t care if I told another one, “No crap is different than the other crap, it’s all crap. You’re just looking to make some money,” he said.

I was blunt in my initial reply and wanted to sound open to his perspective, “I want to know the true story. Not that Helter Skelter crap.” I was bluffing of course. I had no idea if Helter Skelter was crap, but I had seen enough on TV about Manson to know that he saw himself as wrongfully accused. I also selfishly thought a documentary about Charles Manson being innocent would be a must-watch if nothing else.

Charlie replied, “They don’t want to tell the truth about nothing. They would rather die and destroy the planet and burn all the trees down and kill everybody. Hopefully they’ll do it. I mean you can understand that if I was a tree, I certainly wouldn’t like people.” Manson pivoted to an environmental analogy using it as a metaphor for himself. “They’re using me every day man, you cut me down making furniture out of me. Poor tree don’t have a chance. He’s got nobody to help him.”

“So you do care about all that’s been said about you? You want to set the record straight?” I asked.

“People don’t want to look at it from the point of view that brings them to something they don’t like, what they want reality to be,” Manson replied. “They don’t give reality a thought. They don’t care about nothin’. All they care about is food.”

“Then what is reality?” I asked, trying to keep pace with Manson’s stream of consciousness. “All the things that have been said about you? I mean, what is the truth?”

He replied quickly, “The truth? I was born in it!”

What does that mean? I thought. “I want to know the truth. What really happened, not what everyone else thinks they know,” I said. I was looking for a way in, trying to relate in a way other journalists had not. I wanted to express that I thought Manson’s story could be untold and re- told, yet not sound as if I was completely siding with him. I was grasping at straws trying to go toe-to-toe with a mind-controlling serial killer, and to my surprise it was working.

“That’s good,” Manson said. “If I could just get out of this stupid fuckin’ polly-parrot cage. They got me in a cage and everybody’s shooting at me in their own way.” Manson took a long pause. I was about to speak when suddenly he said, “I didn’t have nothing to do with killing those people.”

Holy shit, I thought. A shiver went down my spine; the surreal conversation had escalated. I was speaking with the Charles Manson and he had, unprompted, brought up his infamous murder spree.

Manson continued, “They knew I didn’t have anything to do with it. They didn’t want to hear it. I didn’t get a defense; I didn’t get to put on a trial.”

I thought, what the hell is he talking about? My heart rate was picking up. It occurred to me that I would probably never get another opportunity to speak to Manson again. I decided to be blunt, “If you didn’t kill those people, then who did?” It was a good strategy, Manson liked that I was willing to challenge him.

Manson yelled, “The people that told you they killed them. They stood on the witness stand and said ‘yeah I killed ’em.’” Charlie paused, and I thought for a moment that he had hung up, but his voice came back almost meekly. “Everybody at that ranch did what they wanted to do.”

The ranch was the nickname for the commune where the Manson Family lived back in the sixties. Charlie was subtly telling me he didn’t order the murders—people on the ranch did whatever they wanted, regardless of him.

For a second, I thought, If Manson didn’t order the murders then who did? Before immediately asking myself, Why would you believe anything Charles Manson has to say? Of course he’s going to tell you he’s innocent. What did you expect? I was aware that the time limit on Charlie the call was nearing the end, and I had hundreds of questions swirling around my brain. I decided to ask the obvious, “Why do people blame you then? Why does everyone think you’re the boogeyman if you didn’t kill anyone?”

Charlie said quietly, “They still don’t believe me.”

Charles Manson is innocent, I thought, who on earth would believe that?

The automated voice came on the line abruptly, “You have thirty seconds remaining.”

“Can you call me again?” I asked.

Charlie took another long pause, “I don’t know, man.”

“But if no one knows the truth, we can set the record straight,” I attempted to reason.

Charlie said, “Everybody is for money. Everybody hates me for a dollar.” Charlie’s way of saying, I don’t trust you, you’re just looking to make money off me.

The call abruptly cut out, leaving me to guess if I would ever speak to Manson again. I doubted that I would, as he seemed skeptical of my motives, and I had no intention of smuggling him in a cellphone. I imagined that he was inundated with requests like mine. I wondered why he had now taken the time to call me twice.

To my surprise, he called me again the next night, and over the next month we kept talking.

Sometimes we would talk about things of significance, other times I would just listen to him ramble. In those initial calls, I was incredibly naïve about the specifics of his story. Manson would reference obscure details about his life, and I would say, “I’ll have to look that up.” To which he would reply, “You don’t have to look it up, you just have to look at it.” But after those first conversations with Charles Manson, I did have to look up a lot of things. I watched every documentary and read every article I could get my hands on, and I re-read Helter Skelter carefully.

I had hours of conversations with Charlie and speaking to him over time gave me a fleeting glimpse into how his mind worked. He thought fast and changed subjects at the speed of no one else I’ve ever encountered. At times, he’d begin by talking about prison, then seamlessly transition into his take on the Mexican pyramids, then a quick anecdote about 1969, or a spider he’d watched for days while in solitary confinement, or his views on the environment, race relations, or the very nature of reality. To complicate matters, he referred to everything in context, as though I should already understand. For example, Charlie never explained to me what “Spahn Ranch” was, he simply talked about “The Ranch.”

He expected me to know that Spahn Ranch was the de facto home of the Manson Family. He referred to everyone by the nickname he’d invented for them and he often had more than one name for each person. I had to have those names memorized because Manson would get frustrated if I’d ask him to explain. He expected me to know exactly what he was talking about; he was, after all, the Charles Manson. As he once sharply reminded me, “When I say something you don’t have to look it up. You already know it, ’cause I said it.”

In addition to Day’s book, the Oxygen Channel will air a new documentary he produced called Manson: The Women on Sat., Aug. 10

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.