“The last free place in America”

COULD SLAB CITY BECOME A REPLICABLE ROLE MODEL?

One Man’s Utopian Vision for the Famed SoCal Squatter Community – and Far Beyond

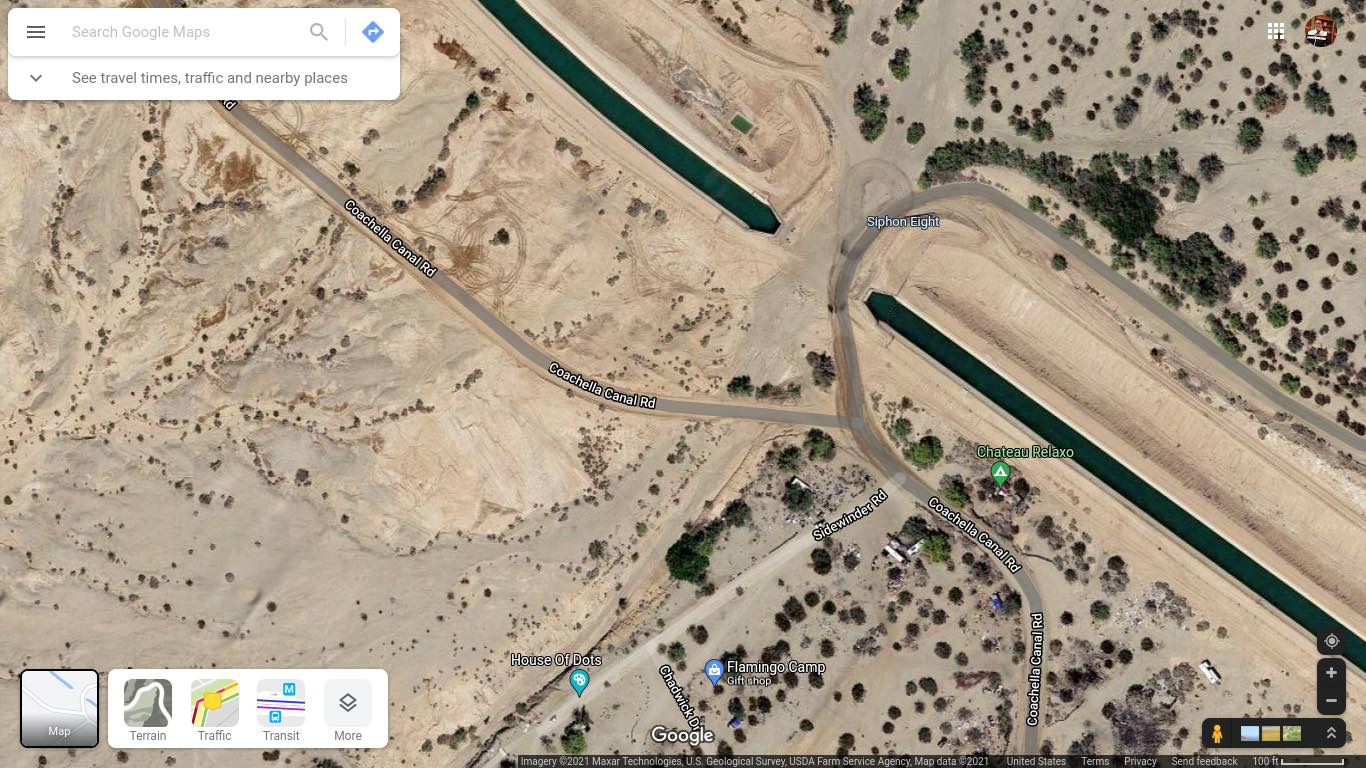

Slab City is a long-established squatter community, deep in Southern California’s Sonoran Desert. Made famous by Sean Penn’s 2007 movie Into the Wild, it’s a barren square-mile scattered with improvised, off-grid dwellings that, since the 1960s, have been springing up around the eponymous concrete slabs of a former military base.

During triple-digit summer temperatures, reaching as high as 130 degrees, ‘The Slabs’ is home to a couple of hundred hardy societal outliers; in the winter months, this swells to thousands. It’s a place where mainstream society’s regulations and restrictions, on everything from nudity and noise, to drugs, building codes and speed limits, are only vaguely acknowledged. The subject of countless articles and documentaries, this ad-hoc, hardscrabble de facto town poses poignant questions about concepts of freedom, materialism, and inequality in one of the wealthiest nations on Earth.

Now Slab City has also inspired the utopian vision of social entrepreneur Steve Dee, the man behind humanitarian organization Jobs-Liberia.com. Centered on providing a basic, government-provided infrastructure for such communities, it’s a concept he believes could be replicated throughout America. Once proliferated and scaled-up, his Slab City idea could have an enormous impact on pressing issues related to homelessness, mental illness, and even sustainable food supply.

“We already have a functioning prototype in Slab City,” Dee explained, speaking from his Los Angeles home. “We just want to improve and expand on it, by giving them free access to the water that is already running through the property.”

Dee is proposing a scenario wherein genuinely homeless people who move to Slab City would be granted access to free, government-provided utilities – water, electricity and sanitation – and internet (the State of California already owns the land). Each individual would be allotted a simple dwelling on a small parcel of land where they could grow organic produce, limited quantities of marijuana, or anything else of their choosing.

At present, Slab City is entirely off-grid. There is cell phone service and a crude Internet café. Residents are allowed to use an adjacent natural hot spring for bathing, or risk an illegal dip in fenced irrigation canals, which flank the site. Drinking water has to be brought in from nearby Niland and stored in large tanks, which is something of a cottage industry in itself, among residents who have serviceable vehicles.

“Slabbers,” as Slab City residents are known, already widely employ solar power, with one even operating a well-established solar-panel business, but only a small scale. This can be just a few solar-powered outdoor lights, a couple of panels powering fans, or solar arrays that power refrigerators and even limited air conditioning in the trailers, RVs, and improvised shacks that comprise Slab City.

Dee believes sustainable energy such as solar power, and even the safe use of human waste as fertilizer (through composting), should be enabled and encouraged in Slab City and similar communities. For example, an adjacent, government-built solar farm – for which Slab City’s shadeless desert setting is perfectly suited – could provide much of the electricity required to vastly enhance the community’s comfort, quality of life, and potential for small-scale agriculture, and thereby offer economic independence for residents.

The idea would be for Slab City, through farming and barter, to be largely self-sufficient. Any excess produce could be sold elsewhere to provide modest cash incomes. Ultimately, once scaled-up, Dee envisions such communities producing healthy, organic food for surrounding “mainstream” populations. All this would be driven and enhanced by Americas’ historic entrepreneurial instincts and frontier spirit – qualities which Slabbers already display in droves.

“If this small prototype works on the Slab City level, we can expand infinitely through the deserts of California, Arizona and Nevada,” he said.

Access to free healthcare, including addiction and mental health programs, would also be provided for any resident who chooses the government services. At present, although there’s a health clinic and a 12-step program just four miles from Slab City, in Niland, that distance can be nearly impossible for residents who lack transportation. But in Dee’s vision, no one would have to get help for substance-use or psychological conditions. Those who feel alienated, ostracized, or judged by mainstream society, can find contentment among like-minded individuals – but in a place with more dignity, basic comforts, and access to tools of personal empowerment, than the existing community is able to offer.

Dee says he simply wants to offer homeless, addicted, and mentally ill people an option other than being forced into shelters, institutions, sobriety – or just dying on the street.

Even taking into account the cost of providing basic utilities to such utopian settlements, Dee’s proposed approach could prove much more cost-effective than the current billions spent on social services, medications, and policing related to homelessness, mental illness, and drug use across America. This would mean less strain on federal and state budgets – and, therefore, on taxpayers.

Dee pictures people being able to come and go from Slab City-like communities, as they please. No one would be made to relocate to such places, nor made to stay. His idea is to create environments that humans will naturally gravitate towards. Crucially, he says, they will truly want to be there.

“If you put something wonderful in front of people, they’re going to come,” Dee continued. “Free land; free water; free electricity; and free internet, and a place where you can grow your own food.”

Such circumstances wouldn’t be for everyone. Far from it. But there’s potential in Dee’s hypothesis for a widespread win-win: people uncomfortable in mainstream society could find their happy place in Slab City-style living, while the mainstream communities they leave behind would experience fewer problems related to homelessness, mental illness, and substance abuse. Thus, The Slabs and similar small communities could provide an invaluable safety valve for individuals to have fun, and live their lives with dignity. To an extent, Slab City already plays this role in surrounding Imperial County.

“Honestly, I would not like to live around so much freedom, because I like structure,” said Dee, who himself battles serious depression related to childhood abuse stemming from his dyslexia. “But if someone else loves it, then I would love for that to happen. Everybody would be happier.”

As he has successfully done with Jobs-Liberia.com – which includes a free barter app to help people trade, sell and buy goods and services within easy walking distance of their location – Dee is aiming to start a viral online conversation about his Slab City concept, and then a petition, that could stimulate government investment in such an idea.

“Ultimately, it’s our duty as human beings to help other people. Really, I think that’s the meaning of life,” he concluded. “Because, otherwise, when you die, what good were you? Did you just eat and play video games? Let’s reboot society and see what happens!”

Article Written by Meloudy Jackson

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.