Photographer Jules Bates and the creative collective Artrouble were responsible for some of the most emphatic, energetic and indelible images of L.A.’s music, art and fashion nexus, encapsulating the exuberance of the punk into new wave scene circa 1980, and foreshadowing in their rampant interdisciplinary extravagance the collaborative zeitgeist of today. Before he died at just 27 years old in a motorcycle accident in September 1982, Bates had already achieved more legendary work than many artists make in decades. Now, his family and his alma mater have joined forces to preserve and disseminate his photo archive, as the ArtCenter College of Design gets set to open the Jules Bates “Artrouble” Center this fall, for the benefit of students and the public alike.

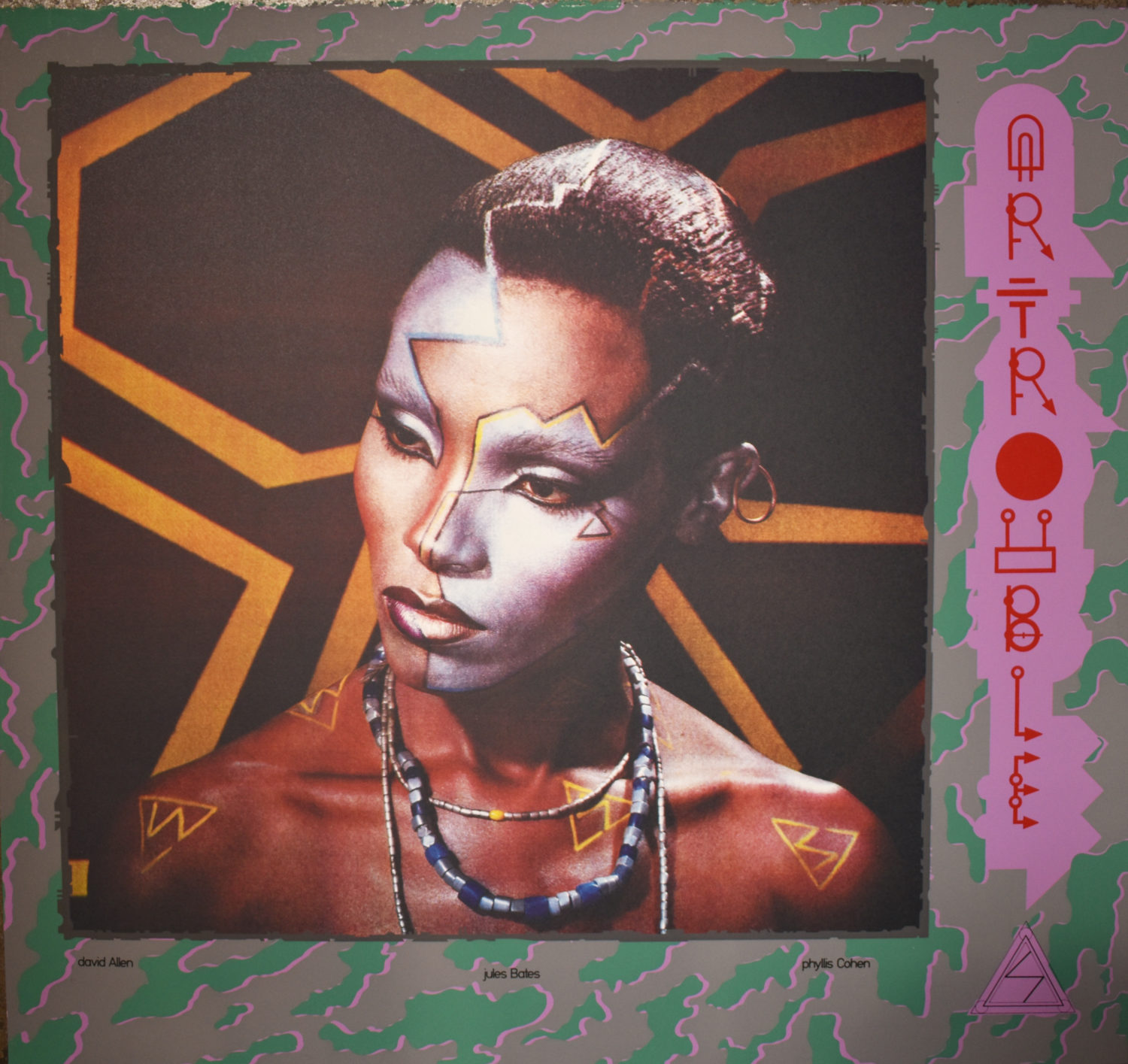

The bulk of the collection is photographic materials shot by Bates — over 200 photo prints, more than 500 rolls of negatives and transparencies, with hundreds of single negatives and slides. At the same time, foundational to the collection is some of the brilliant work Bates made as part of the group for which the center is named — Artrouble, a seminal creative agency which he co-founded in 1976 with make-up artist Phyllis Cohen and artist and graphic designer David Allen.

Asked for his memories of Jules and Artrouble, Allen responded saying, “Jules Bates is a strong presence in the hearts of his friends and family and will be forever missed but I want people to see what a visionary he was and how he affected photography and the world he lived in,” and went on to pen a lengthy, frank and heartfelt essay, published in its entirety here, in which he recounts several inflection points across his relationship with Bates — including how they met.

“The Masque nightclub had recently opened, giving the new scene an actual venue for bands to play and foment — serving the same function as CBGB’s in New York or the Roxy in London,” Allen writes. “I had recently designed a flyer for the young Scottish club owner that used a photo of Scene It Girl Trudie. At the club one night I was approached by a guy I’d seen around but not spoken to.”

“‘You designed that flyer with Trudie on it?’”

“Yeah.”

“‘I have a project and I need a designer.’”

This was Jules and we got talking as the music crashed around us.”

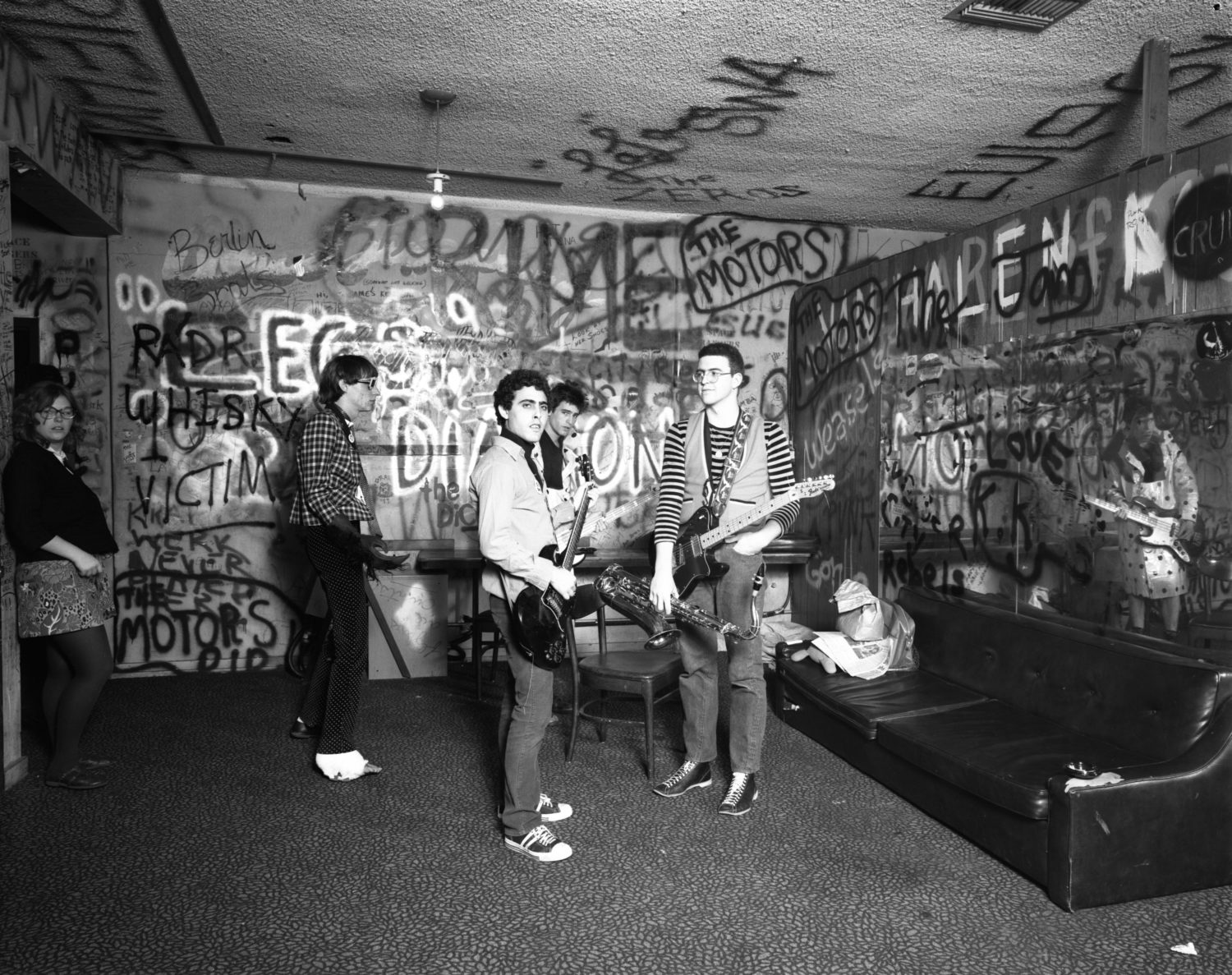

The Dickies backstage at the Whisky, circa 1978. Photography by Jules Bates.

Indeed of special interest to music aficionados are the Center’s trove of images — commissioned, staged and candid — of L.A. punk clubs from the late 1970s, including the Masque, Whisky-a-Go-Go and the Plunger Pit, as well as punk and new wave bands and musicians like The Deadbeats, Howard Devoto, Brian Eno, The Go-Go’s, The Mumps, The Plugz, The Screamers, The Weirdos and X. The collection further encompasses Artrouble works and ephemera, including exhibition postcards, prints, uncut album cover proofs and completed album covers from musicians like DEVO, Oingo Boingo, Billy Idol, The Dickies and The Motels, as well issues of publications such as L.A. Weekly — where he was among the paper’s earliest photo editors.

Ewa Wojciak, art director at the new Weekly, had Jules as her photo editor at the paper, as well as working with him at the same time elsewhere such as at her publication NO Magazine. “Everybody loved Jules. He was my neighbor,” Wojciak recalls, “and my best friend. He was a visionary, an amazing talent, a cool guy, a workaholic. He had a real vision as to style and beyond. He had not yet achieved everything he had to do. He was charismatic, adventurous, a seeker and a boundary-tester. He was great to work with and fun to watch. He would look around him and really use it all. He loved what things were, and he loved what they could become.”

L.A. in those days was a small scene and, Wojciak says, “The Weekly was the center of it, all the bands had to get their listings in and a lot of those people worked there. I was the first art director. Maybe Jules was the first photo editor, certainly one of the first. Did I hire him? Probably. I hired everyone in the art department.” He shot the covers, and Dennis Keeley worked with him and then became the photo editor after Jules left. “Jules just outgrew it,” Wojciak says. “He outgrew everything.”

David Allen recalls that at the time, “The U.S./U.K. media had already pigeonholed the new ‘punk’ scene and their approach was strictly safety pins, leather and spit. We were out to change that. Most L.A. punks dressed retro in some way which, compared to the flared denim and double-knit preferred by 70’s SoCal hipsters, looked totally futuristic and inspired what became new wave in the 1980’s.”

Artrouble silkscreen. Photography by Jules Bates, makeup by Phyllis Cohen, design by David Allen.

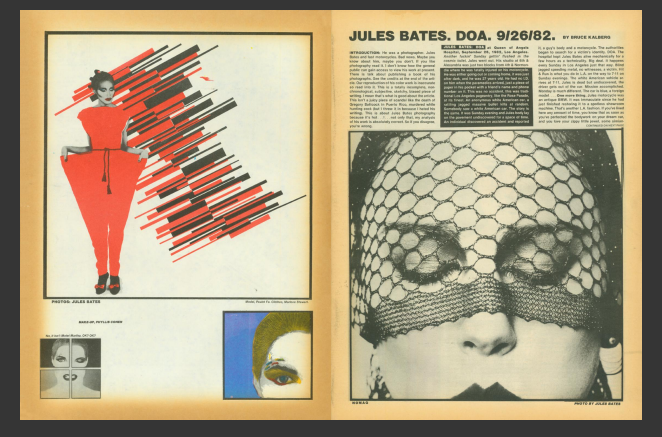

But as Wojciak’s partner the late Bruce Kalberg wrote in NO Magazine after Jules died, “[Bates] was being pigeonholed as ‘new wave’ and he backed off from lack of interest in the trend when he pursued personal work… His fashion work, in spite of its attractiveness and grace, was commercially a flop… and he continued to develop it obsessively… Its elegance is deceitful because the entertaining seductiveness diverts the eye from the work as a study of pictorial space. Fashion as a universally pictorial space was used by Jules as a vehicle to lead the viewer into an abstract dimension… Jules was nearing a point of departure where a photograph wasn’t anymore a photograph.” — excerpt from “JULES BATES. DOA. 9/26/82” in NO Magazine, Issue #10 (1983).

“All this while Jules was getting more fashion work which involved Phyllis Cohen more than me,” says Allen, “but that added to my experience as an art director in the future. Many stylists and models were happy to work gratis as they knew their work shot by Artrouble would jump out of their portfolios. In turn, Jules’ unique style was being seen by more people. One day we went to visit Matthew Rolston who had a studio on Highland and wasn’t very famous at all at that time. I think they’d been at ArtCenter together. Matthew was falling over himself gushing praise. It seemed funny at the time and then a short while after Jules died when I was living in New York, Rolston became the most famous photographer in the world and it didn’t seem funny anymore.”

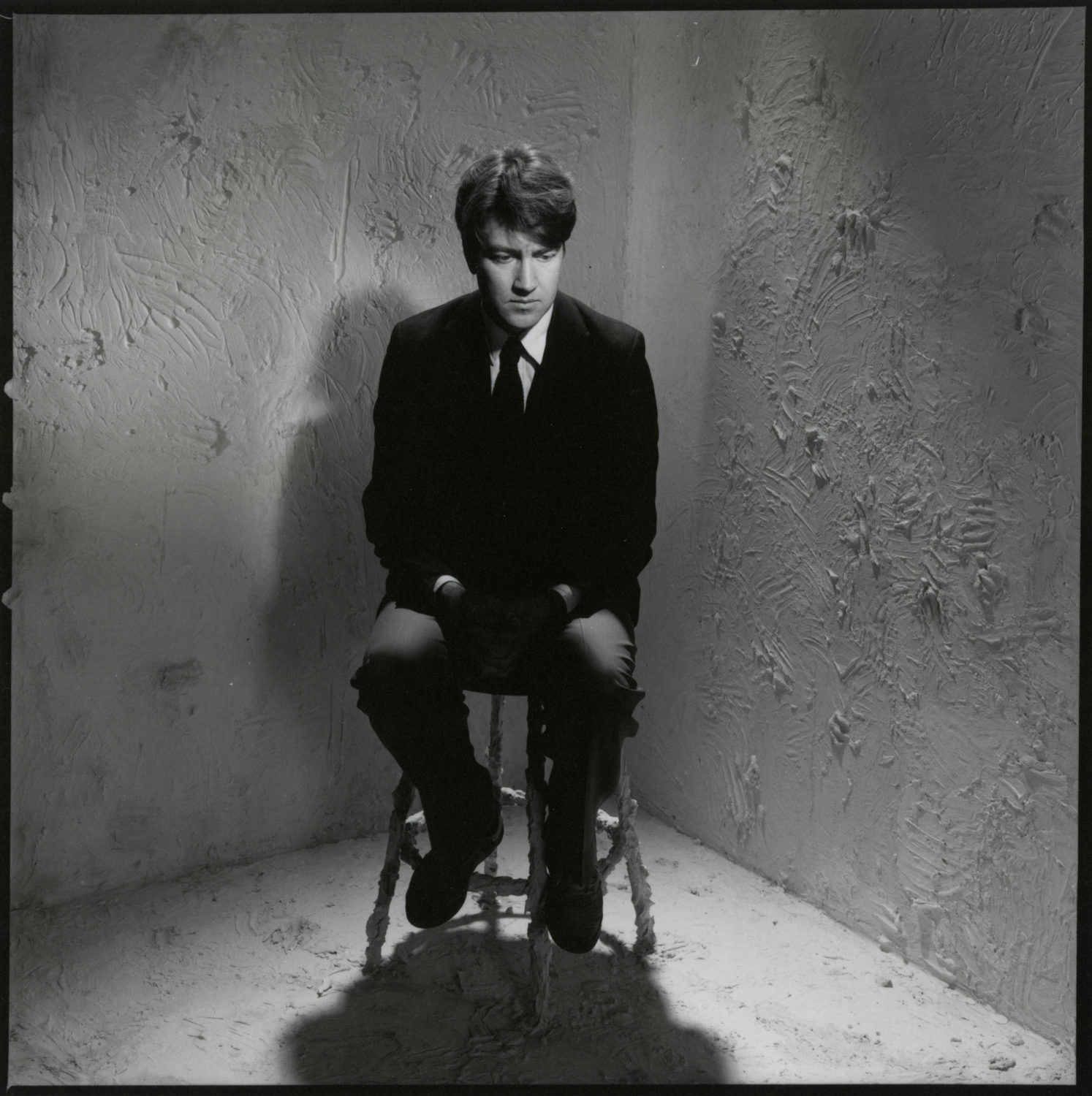

David Lynch portrait for L.A. Weekly, circa 1980. Photography by Jules Bates.

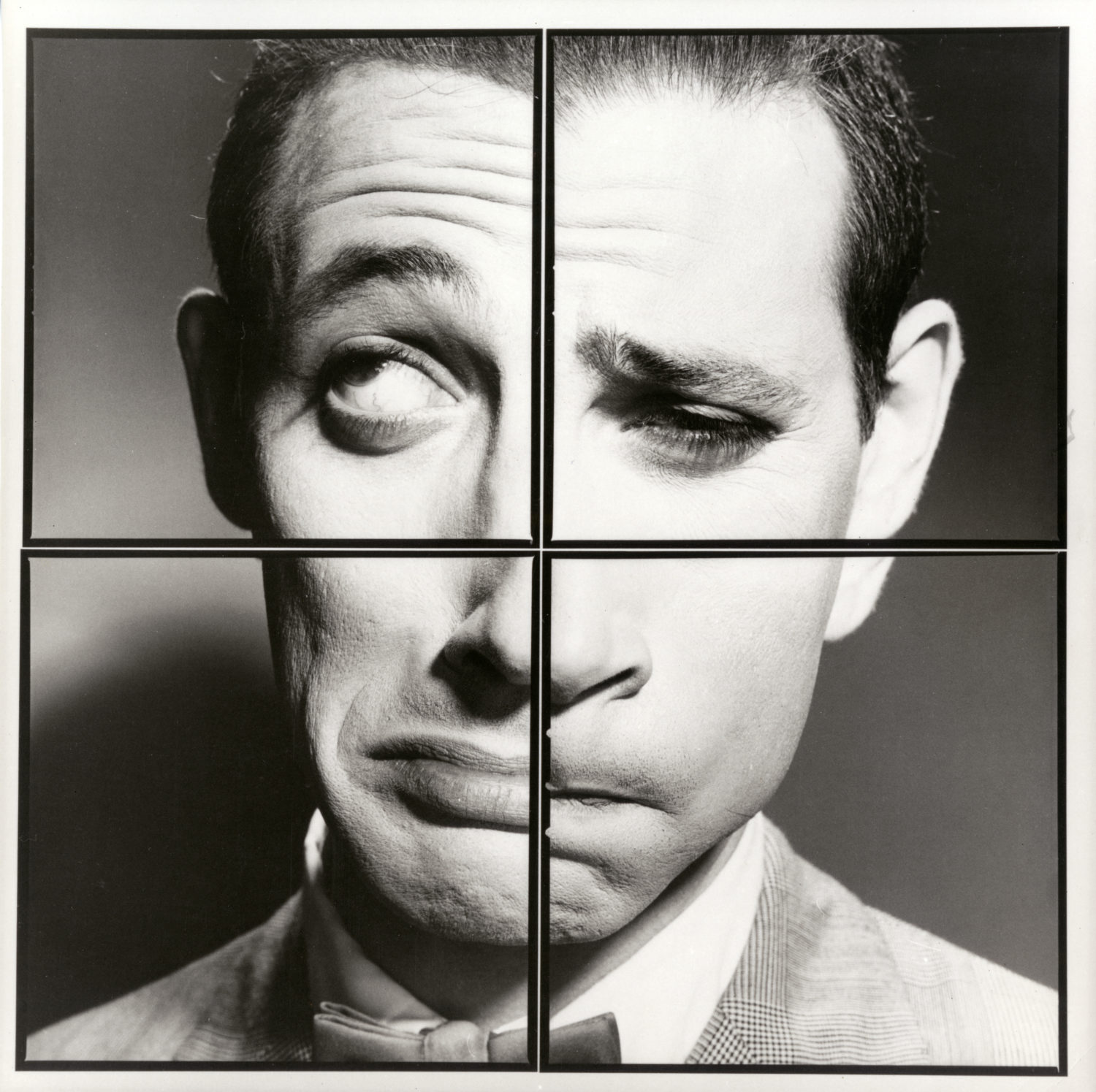

And in the Artrouble Center holdings there are pictures from some absolutely wild fashion shoots, and iconic portraits including Charles Bukowski, Buckminster Fuller, Pee-wee Herman, David Lynch, Marshall McLuhan and Harry Dean Stanton. Among these are examples of his trademark “quartering” portrait construction, top secret color-processing sauce, compositions embodying Artrouble’s genius for conceptual make-up and integrated set-building, Bates’ proprietary color-processing technique, and, marvelously, DEVO’s Freedom of Choice album cover — the one with band wearing their signature “energy dome” helmets. This iconic image was created by Bates — at least two different sources recount that the pots-on-heads moment was an Artrouble idea.

DEVO from Freedom of Choice album photoshoot, 1980. Photography by Jules Bates.

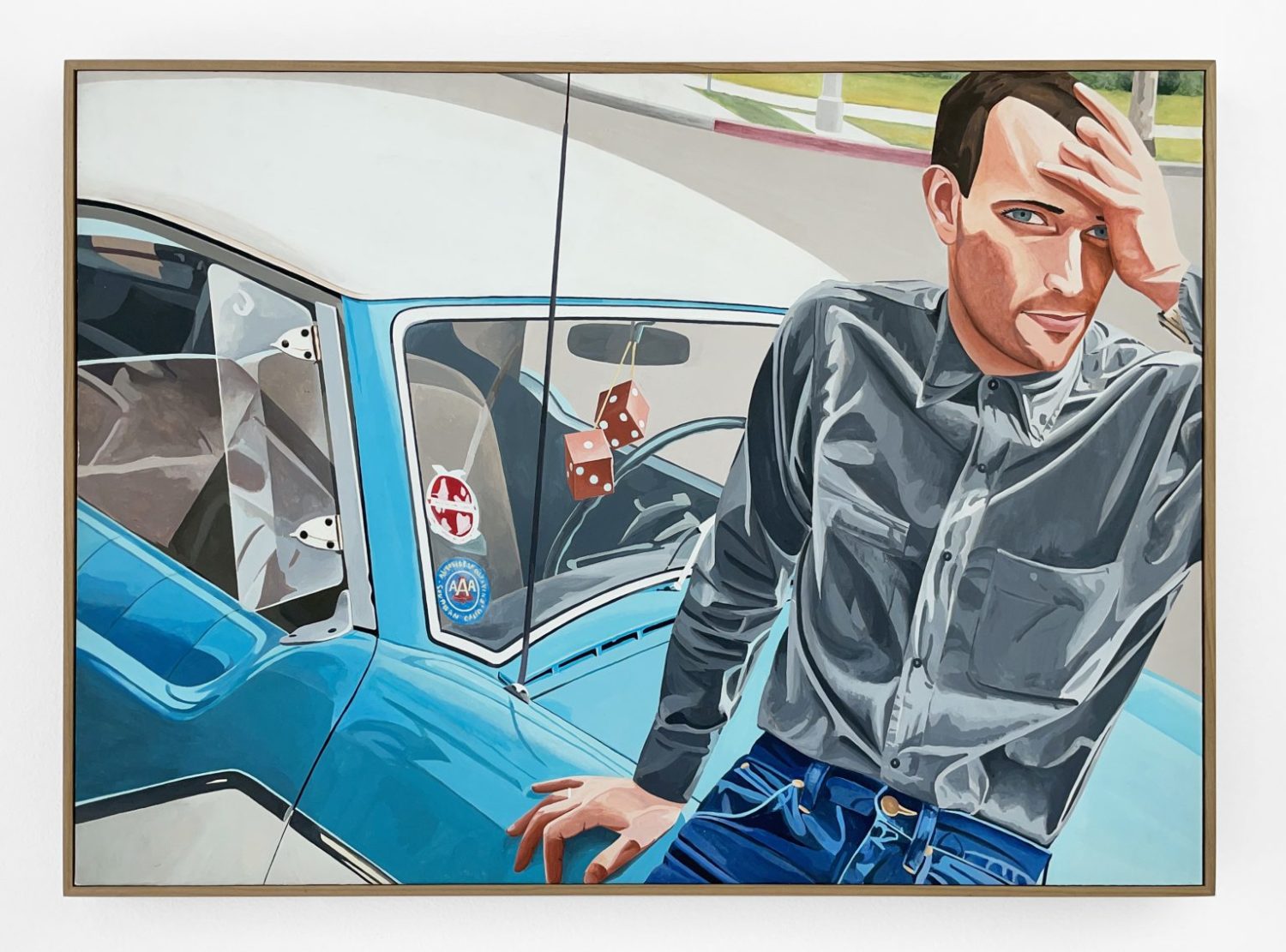

One of the people who related the DEVO story was the artist Nick Taggart. Taggart is an interdisciplinary artist and designer, who currently has an exhibition up at Odd Ark Gallery, showing his radiant portrait paintings from circa 1980 depicting the same scene as Artrouble; no surprise to learn that they were all friends. One of the paintings in the show is a dazzling and cheeky portrait of Jules and his younger sister Melissa Lora — an ArtCenter Trustee and a keeper of the family’s commitment to Jules’ memory and legacy — purchased the painting from the show in order that it be hung in the new space. Taggart — who quite coincidentally is currently ArtCenter faculty — could not be more honored by this development.

“The show is really a window into a lost world,” Taggart tells the Weekly. “Jules was a scene like the Chelsea Hotel, and we are seeing all of this now through the lens of history. I remember Jules was always working on this BMW motorcycle, like restoring it in his living room and then he’d go out and make these really refined fashion photographs like George Hurrell. We were all interested in art history, how AbEx became Constructivism and then Hard Edge over time. We weren’t just one thing, it was an exciting scene of like-minded people, and Artrouble was like a band, they pooled their skills to do the more complex things.”

Beyond the foundations of his very solid technique, Bates deftly took everything he learned and reinvented it, says Taggart, who also cites the DEVO flower pot suggestion as evidence of this casual genius. “The record business (where I also worked) was more eager than the fashion world for the Artrouble kind of risk-taking. We both worked at Warner Bros.; we had the room to be creative. When he got the Go-Go’s to put their hands in the paint and smear it all over the set themselves, that kind of spontaneous inspiration captured the energy of Artrouble. Then with Phyllis Cohen doing the make-up, with David Allen’s graphic sense, with collaborators like printmaker Richard Duardo, it was more like art than anything else.”

Nick Taggart, Jules, 1980, Acrylic on board, mounted on panel, 20.5 x 28.5 inches (Courtesy of Odd Ark LA)

Everyone knows the story of how Jules lost some of his fingers — building a rocket in the family garage with his older brother at ages 17 and 14. He was very proud of this and would flaunt it. “I was taking pictures of him and Phyllis in the car,” Nick recalls, “and he posed with them out like that; he did that all the time, it was his signature pose.” Ewa has many photographs of him doing the same thing, hiding his face behind his hand in a way that draws attention to both the injury and the twinkle in his eyes. “Jules dying was a shocking event,” says Taggart. “You think you’re invincible at 27, you live dangerously. Imagine what he could have done.”

“He had a real interest in popular culture,” says Wojciak. “He’d find interesting people, create a scenario, get them to the studio… I have taught photography at ArtCenter; I’ve still never seen what he did replicated. The Devo portrait! He was genuinely interested in art, he’d research like Rodchenko, the New York School — none of that was casual or coincidental, he was teaching himself.”

“He had this technique of chromosaturation,” says Taggart, “of turning the color up to 11 and having a whole conversation with painting, with Dada, with modern abstraction. It was way more than ‘here’s my style.’ He had multiple styles, it confused some people!”

NO Magazine, Issue #10, 1983

From Bruce Kalberg’s writing again: “Jules was a fanatic colorist, and to achieve the results he wanted he used a special process, which everyone can’t quite explain, called in photo jargon “chrome negative”… “Chrome Neg.” Professional slang to make the uninitiated feel like jerks… Still, if you pin them down on a specific term and forced them to explain it, most professionals don’t know a fucking thing… Jules was essentially using only the techniques and tools of traditional studio color photography, unretouched.” — excerpt from “JULES BATES. DOA. 9/26/82” in NO Magazine, Issue #10 (1983)

Wojciak too was always blown away by Bates’ versatility, innovation and the powerful appeal of the Artrouble look he created with Phyllis and David. “The human figures were integrated into the space, which was thus flattened; it was all on one plane. It was unusual and very much that early new wave thing of flying shapes and striking patterns. Beyond portraiture, he went the extra mile.”

Bates’ younger (by seven years) sister Melissa Lora has been a driving force behind the preservation and expansion of Bates’ legacy. “The life he lived was full of joy and synchronicity, and positive energy being generated every step of the way,” Lora recalls for the Weekly. “I miss Jules so much, he was so amazing. I’m still learning new things about my own brother, the story is still expanding. His scene, it was the underground beginning of something that became huge later, it gives me the chills sometimes. For such a young person, he touched so many lives.”

Lora has been an ArtCenter Trustee since 2015. Having managed with her parents the materials in the collection since Jules’ death in 1982, she first mentioned the idea of housing Jules’s archives at the school in late 2018; the first official meeting was in February 2019 with Director of Archives and Special Collections Bob Dirig, College Librarian Mario Ascencio, Senior VP of Development Emily Laskin and Development Director Amy Swain. Melissa and her nephew (also named Jules Bates, also a photographer, also an ArtCenter alum) discussed transferring the collection to ArtCenter along with a substantial gift to create what would become the physical Jules Bates “Artrouble” Center. The family was already a major supporter of both ArtCenter and her brother’s legacy there, and had donated royalties to the Michael Bates and Jules Bates Memorial Endowed Scholarship..

“My parents were so strong in keeping the memory alive and wanting the work to be seen,” she says. “At ArtCenter they’ll be able to digitize everything, integrate it into the curriculum, and it will build on itself. Every time I go on campus Jules lives for me. The more time goes by, the more clear it becomes just how special he was,” Melissa says.

“Our father was a painter, but also the breadwinner; he never got to pursue it. Jules lived out the best of Dad’s dream and Dad was so proud of him,” says Melissa. Her nephew Jules Bates remembers it the same way. “Grandpa was an artist,” he says. “When he was semi-retired he took up painting again. I remember him telling me how he didn’t have the opportunities that my uncle and I had. How he’d been working from twelve years old, never went to college, how he wishes he could have had a career in art — so he was really supportive of me, maybe even more so because he had seen what Jules had accomplished.”

Jules the younger has been aware of his uncle’s work for as long as he can remember. He himself first became interested in photography through skateboarding and live music, taking pictures of his friends and of the shows and bands, not unlike his uncle. But it was more of a hobby for him, until it was time to go to college. “There comes a time you have to decide what to do with your life,” he says. “It’s not that I chose to follow in my uncle’s footsteps per se. But I don’t know if I would have even realized that was an option if it weren’t for him.”

“Jules’ time at Art Center sort of forced all this explosive creativity into a professional foundation,” Melissa continues. “While he was going there, he lived at home and the garage was his studio. Phyllis was a fellow student, we’d have models over, in the bathroom of our suburban house in the Valley, all the time.” Once they had Lance Loud from the Loud Family at the house; Jules emptied the freezer in the garage, filled it with dry ice and put Lance in there naked all curled up. “He was a playful and complicated person,” she says. “His missing fingers! He was so proud of that!”

Pee-wee Herman, circa 1980. Photography by Jules Bates.

“All my adult life I’ve been meeting my uncle’s friends,” Jules says. “They’ve had an interest in getting to know me. It’s been great to hear these stories, to know that it wasn’t just my family telling me about these things — the DEVO hats! Pee-wee Herman! — but to know that wow he really did do all that.” Bates is a photographer, especially a portraitist of musicians and personalities, and also runs a motion capture company. “Yeah,” he says, “They are big shoes to fill.”

In the end, Melissa and her husband Michael donated a million dollars to ArtCenter – $500,000 toward the archive and another $500,000 to support the scholarship. For Director of Archives and Special Collections Bob Dirig, the chance to not only create a bigger, brand new archive room that would preserve all manner of important ArtCenter materials and offer a place for students to do research and reflect has been a dream deferred — until now. The property at 950 S. Raymond Ave. in Pasadena will house a significantly larger facility for the College Library’s Archives and Special Collections, which will feature a dedicated research room in the form of the Jules Bates “Artrouble” Center.

Dirig is beyond excited to dive into the materials, tease out what is personal and what is commercial, and to start the process of integration with the school’s programs in photography but also fashion, graphic design, and more. “Bates was really just an integral part of the scene, so it all flows together,” Dirig notes. “Part of the cataloging job will be sorting some of that out in the narratives,” he says, and soon there will be programming, publications, loans, exhibitions, and maybe even some kind of crowd-sourced database or oral history component to go along with it. “It’s finite but it can still grow in a number of ways,” he says. And as for the famous DEVO album cover? “It was just a loose slide that kind of fell out of something else, and I said, oh my god that’s the ONE!”

Photograph of model Kathy Jeung. Photography by Jules Bates and makeup by Phyllis Cohen.

Before the “Arttrouble” Center appeared on the horizon, Lora’s parents had previously already created and endowed a scholarship at ArtCenter, guided by Dennis Keeley, the erstwhile Chair of Photography — and as it happens, the photo editor at the L.A. Weekly after Jules.

“I met Jules at the Weekly with Ewa and Robert Lloyd, who I was in a band with,” Keeley says. He was hired in photo production and became good friends with Jules. “He was shooting covers and I was starting to shoot insides, he’d pass some jobs on to me. About a year after I started there, he was thinking of leaving to go pursue his other work and he said, ‘I think you could be the photoeditor — just make sure you still hire me sometimes!’ I shot musicians for 30 years — five of them at the Weekly, and then I started teaching.” Keeley was at ArtCenter as Chair of Photography from 2003-21. “While I was there,” he says, “one of the most satisfying and consequential things I accomplished was setting up that scholarship [with the family].”

“We were friends,” Keeley says. “His death was a personal tragedy for me. Jules was a reckless guy but he made big, beautiful work. The idea for the scholarship came about, I think it was when I saw the family on campus at an open house event and they said they still think about Jules every day and I said, so do I. His voice is really missing from today, it’s been sorely missed for decades. With Melissa’s lead, out of this tragedy the family has made something really meaningful.” Bates learned his fundamentals at ArtCenter, says Keeley, “then he took his spirit and channeled it in a really productive, important way. For his collection to become a resource for students now, across disciplines, is amazing. Jules was supposed to be here — and now in a way he can be.”

For more information about the Center, visit: artcenter.edu; for more information on Artrouble, visit the online archive maintained by David Allen at: facebook.com/artrouble.historic.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated that Ewa Wojciak was the “first art director of L.A. Weekly.” Ms. Wojciak was actually the third art director of the paper (after Nancy Steiny and Tom Martin). It was also misstated that Mr. Bates was, “Maybe the first photo editor.” Mr. Bates was actually the second photo editor (after Jeffrey Scales and before Dennis Keeley).

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.