Here are the things no one will say in public but have likely thought at some point in their lives:

Black men beat their women. Black men sell drugs. Black men aren’t smart. Black men aren’t emotionally available. Black men don’t raise their children. Black men aren’t gentle. Black men abandon their families. Black men are angry. Black men don’t smile. Black men are criminals. Black men. Black men. Black men.

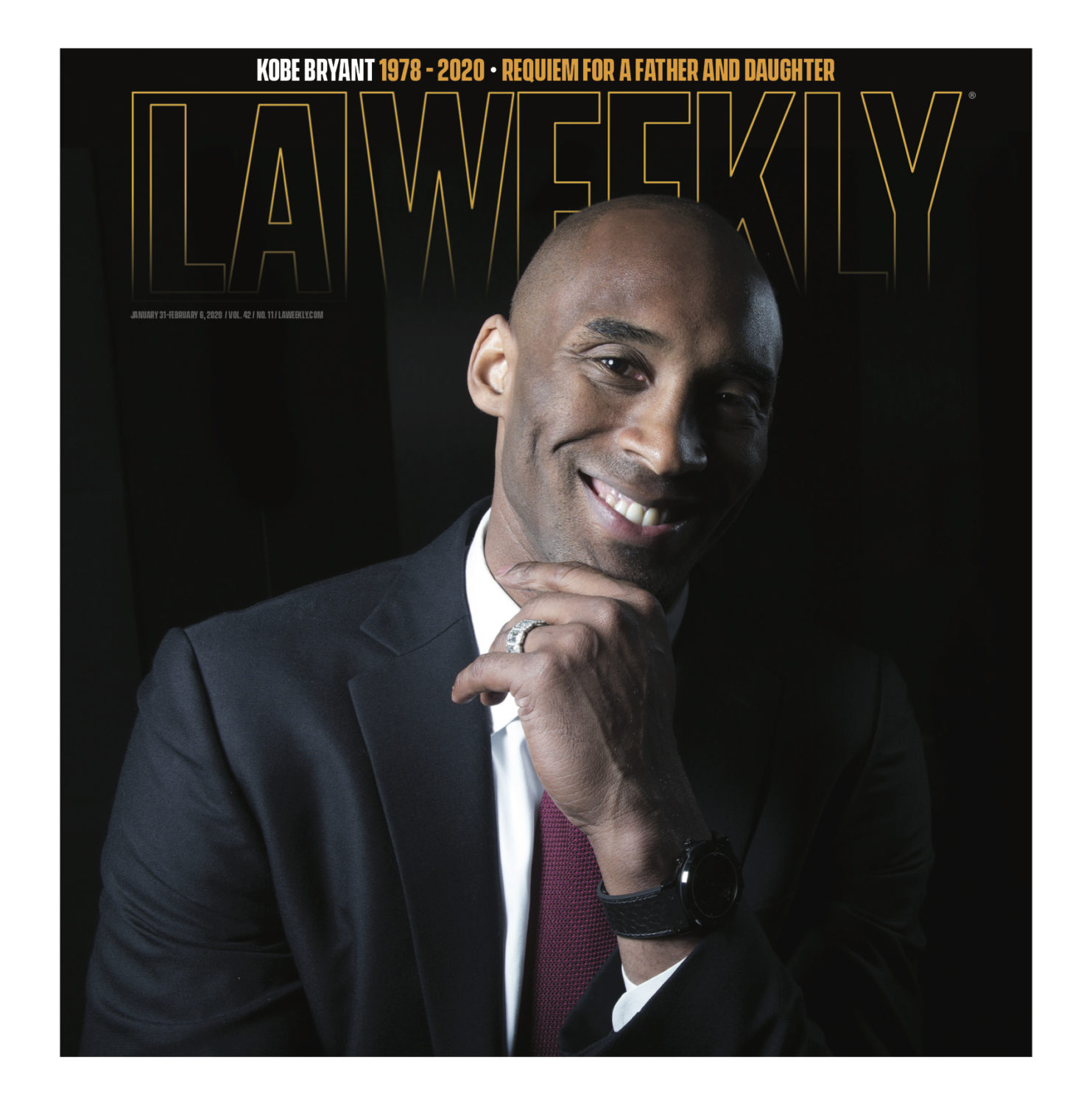

Over the duration of his 20-year basketball career and his life off the court, Kobe Bryant, a black man, refuted the above stereotypes through his athleticism, his mentorship, his parenting, his image and courage, and his intellect, work and words. With the exception of one fallible, high-profile instance, he was the ultimate hero. He wasn’t a king or saint, but he was ours; every black person is thinking this right now.

When I heard the news of 41-year-old Bryant’s death from my daughter in Brooklyn, my heart rocked a little in my chest. A good brother gone. A black man who didn’t fit the intrinsic bias that haunts and lingers in the American cultural imagination was dead.

Feeling the communal loss, I opened Instagram and actress Tia Mowry-Hardrict’s post popped up first: “OMG! I can’t[sic] I’m crying hysterically! We just saw you in your car!” I scrolled through more, reading the sincere outpouring of sorrow, incredulity and disbelief at the tragic death in a helicopter crash of the former NBA All-Star and MVP turned businessman, producer and author. Political pundit and activist Shaun King tweeted, “At whatever cost, the Staples Center should be renamed after Kobe Bryant.”

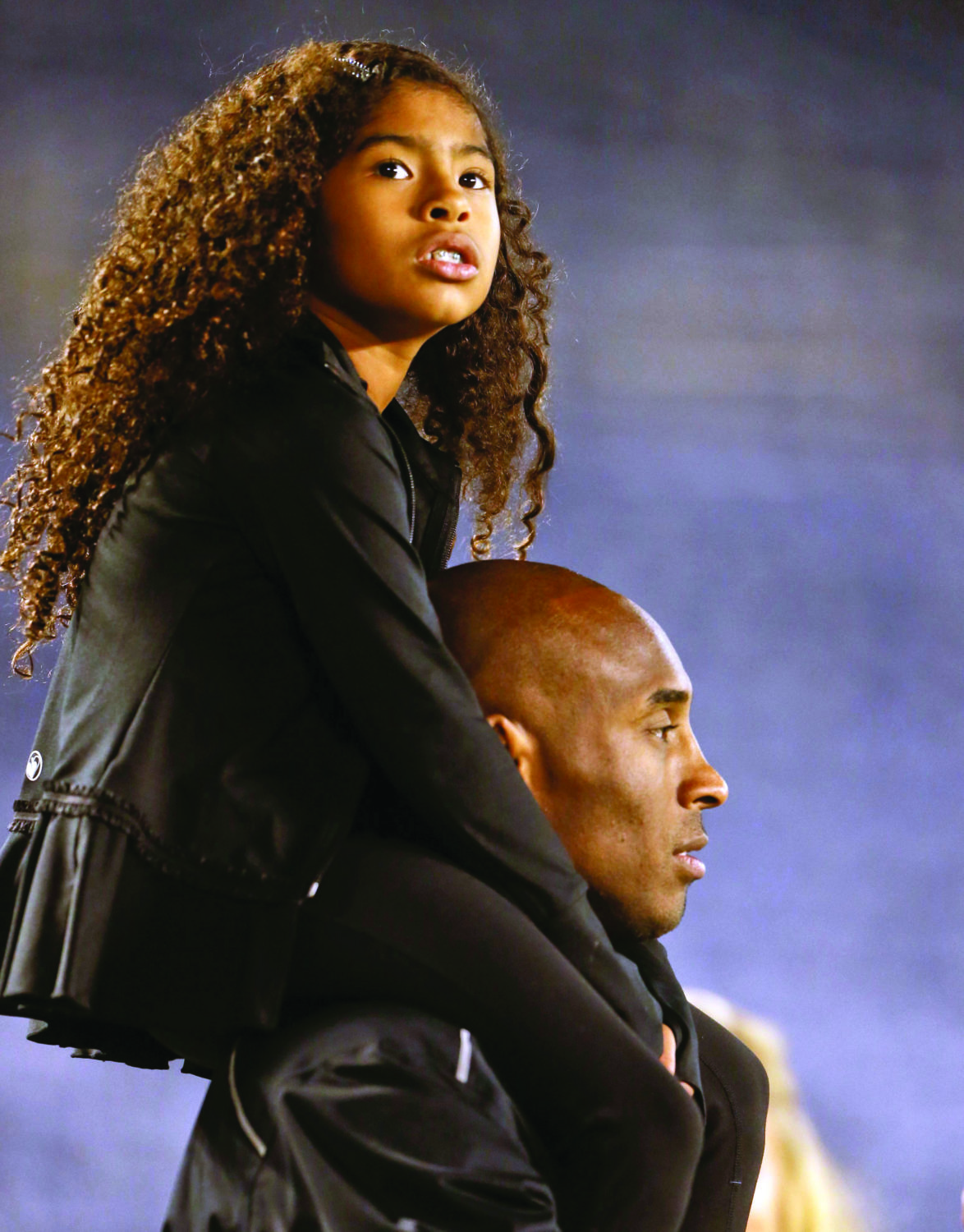

But when I saw the picture and caption that 13-year-old Gianna “Gigi” Bryant had died in the crash alongside her father, my heart fell out of my body. In all their photos, Gigi’s smile was unfettered and carefree, and with her father’s arm around her in most shots, she looked strong and poised. There was magic in her eyes. That smile, like her father’s smile, said, “I’m taken care of; I am loved. I am cherished. I am a mixed-blood girl who is loved by her father and mother. I am loved.”

(Photo by Lenny Ignelzi/AP/Shutterstock)

Of course she was. A budding basketball star herself who attended Sierra Canyon School in Los Angeles, Gigi thankfully didn’t grow up with the pervasive negative depiction of black men. Gigi’s father was the stuff of legends: Drafted out of high school in 1996, the Philadelphia native was the youngest player ever at age 18 in the NBA; an upstart who seemingly antagonized teammate Shaquille O’Neal with every dribble; at the helm of five NBA titles for the Los Angeles Lakers in 2000, 2001, 2002, 2009 and 2010; an Olympic gold medalist; and upon retirement in 2016, he entered a second act of entrepreneurship as a venture capitalist, producer and children’s book author. Kobe, named after the Japanese steak, showed up to Gigi’s basketball games and avidly coached her, yet he also encouraged and mentored thousands of youth over the years.

But for the black community in Los Angeles, nationally and worldwide, Bryant was a symbol of everything American society said black men were not and could not be: educated, fluent in other languages, successful, kind, good, happy.

While Kobe Bryant was not perfect (he was acquitted of a sexual assault charge in 2004 and settled with his accuser out of civil court), his personal life and actions as an athlete, a husband, a father, a businessman and an author removed him as far from most of these stereotypes as a black man could get. His legacy will remain conflicting for some; and just as those feelings are valid, so is the sorrow felt by those he inspired — and he inspired so, so many.

As an Angeleno, like Nipsey Hussle, Bryant not only represented the spirit of Los Angeles’ community pride and grassroots engagement. He raised our emotional currency with his consistent work with youth. We saw him on basketball courts; we saw him at parks and at the store. Unlike some high-profile celebrities, athletes or rappers who stay in their lanes, Bryant embraced his role model status. Despite his youthful arrogance and his human errors, Bryant grew up, sought redemption and brought us with him on that journey.

As an Angeleno, like Nipsey Hussle, Bryant not only represented the spirit of Los Angeles’ community pride and grassroots engagement. He raised our emotional currency with his consistent work with youth. We saw him on basketball courts; we saw him at parks and at the store. Unlike some high-profile celebrities, athletes or rappers who stay in their lanes, Bryant embraced his role model status. Despite his youthful arrogance and his human errors, Bryant grew up, sought redemption and brought us with him on that journey.

The succession of tributes that occurred Sunday attempted to convey what Kobe meant to his fans. The Dallas Mavericks retired the number 24 in honor of Bryant; in Reggio Emilia, the Italian town where Kobe attended school for several years publicly mourned; Alicia Keys and Boyz II Men opened the Grammys with a tribute at the Staples Center (which Keys called “the house that Kobe built”); fans gathered at the crash site and outside of Staples; and The Forum was lit up purple. In the days after, more then 1 million people signed a petition for the NBA to replace its logo with Bryant’s image.

Former President Barack Obama tweeted, “Kobe was a legend on the court and was just getting started in what would have been just as meaningful a second act. To lose Gianna is even more heartbreaking to us as parents. Michelle and I send love and prayers to Vanessa and the entire Bryant family on an unthinkable day.”

In South Central — not South L.A. — and particularly in Leimert Park, droves of mostly black people walked slowly down sidewalks, stunned, nodding to each other in the coffee shops, stopping to mince the tragedy of a father and daughter’s deaths, and send up prayers for Bryant’s widow and their daughters, 17-year old Natalia, 3-year old Bianka and the newest baby, 7-month old Capri.

As parents, we are grieving with her; as black parents and, for myself, a mother and new grandmother, I — we — cannot imagine what Vanessa and the Bryant family are going through right now. There are no words for this kind of grief. Now, later or ever.

After witnessing the life and capacity of love for his wife and daughters, for all that he was giving to his respective communities, for the legacy Kobe Bryant left us, a young black man who hustled on the court and off the court, here are the things we should be thinking and saying in public now:

Black men are beautiful. Black men are smart. Black men are emotionally available. Black men are winners. Black men are good. Black men love their children. Black men are gentle. Black men take care of their families. Black men are executives. Black men can get angry, but they still love us. Black men can make mistakes that don’t have to define them. Black men. Black men. Black men.

In a 2017 Goalcast interview, Bryant shared that what he (Bryant referring to himself) realized is that, “the most important thing in life is how your career moves and touches those around you and how it carries forward to the next generation….. He realizes that’s what makes true greatness.”

Thank you, Kobe. Thank you, black man in America. Thank you, Gigi, for your all-to brief magical smile. Rest in power.

Shonda Buchanan is the author of five books, including the memoir Black Indian, the tale of a mixed-race Midwest family caught in an intergenerational bi-ethnic and tri-ethnic identity crises. An award-winning poet and educator, Shonda is editing her first novel about black/American Indian intersections, a second memoir and a collection of poetry about Nina Simone. Shonda teaches at Loyola Marymount University.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.