When the LA Phil first staged their landmark interpretation of the durational 19th-century Wagner masterpiece Tristan and Isolde in 2004 and 2007, featuring legendary avant-garde director Peter Sellars, acclaimed video artist Bill Viola, and game-changing conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen, it fairly redefined what classical music and opera could look like in the 21st. They not only pared down awkward previous attempts at full theatrical versions of what Sellars feels is really an epic symphonic poem rather than a proper opera, but also expanded it in exciting new directions with the innovative idea of a full-length video companion.

As Sellars’ pared-down staging focuses the mind on the music and the text, Viola’s work mirrors the vagaries of time, memory, and desire that animate and roil the inner lives of the characters. Now, as Gustavo Dudamel conducts the revival of this production and Sellars returns to helm, the legendary director sat down with L.A. Weekly to discuss the poignancy of revisiting this material nearly 20 years later — in the context of the intervening history and the newness of the present moment, the deep psychological and spiritual underpinnings of the work whose meanings continue to reveal themselves, and the power of the visual arts in esoteric storytelling.

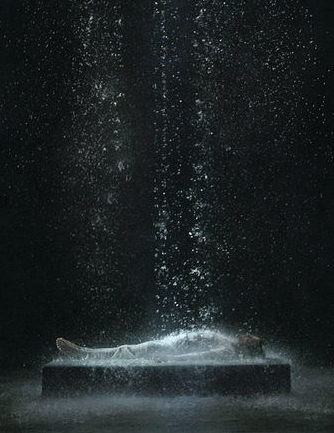

2007 LA Phil performance of The Tristan Project; video by Bill Viola

L.A. WEEKLY: These days contemporary visual artists collaborating on opera productions is pretty common — Mark Ryden, Will Cotton, Tacita Dean, RETNA, Gronk, Christopher Myers… and many others. I’d say you and Bill Viola essentially sparked that with those first productions of Tristan in 2004 and 2007.

PETER SELLARS: There are these dreams you have that opera is just the plural of the word for work; it means “the work.” And so you want a great poet, and you want a great musician, and you want a great painter, and you want a great dancer, and you want a great singer, and you want a great actor. People come together who each do something amazing in their own worlds. But now these worlds are interpenetrated and you’re into a synesthetic thing. For me, one of the most beautiful aspects of working with visual artists in the performing arts is that on a good day, someone will spend maybe two minutes with a painting they like in a museum or a gallery — but what does it mean to spend 90 minutes in front of a painting, or in this case, a video? It’s transformative. What’s so satisfying is to be able to actually be in the presence of a work of art for this extended period of time, where the work itself is changing and is moving through different phases, telling more than one story.

And, you know, that’s all in Bill’s work, that’s been in Bill’s work from day one. I very much wanted to work with Bill in the theater, and he just could never do it. And then we had this kind of amazing moment where he called me and he was doing his mid-career, 25-year retrospective at LACMA, in 1998. He said he had 17 big pieces all in one space. And normally with Bill, all the pieces exist in isolation. But for the retrospective, there had to be 17 of them. So somebody had to come and ask, How do they interact? What’s the shared space? What’s the space where all of these things coexist? What do we hear? So we went into this really elaborate process in which he invited me to come work with him in a museum. And that got us going. It was a little while after that that I worked up the courage to propose this project.

2007 LA Phil performance of The Tristan Project; video by Bill Viola

LAW: Was there resistance to the idea? Were there old guard opera folk that were skeptical of putting a movie in an opera? Or was everybody on board from the start?

PS: We didn’t do this in opera space. We did this in a symphony space. And for me, the whole point of Tristan is that it’s not an opera, it’s some whole other thing. And it’s always ruined by being turned into an opera. But Wagner did something that goes way beyond opera. It is this weird state of consciousness; it is hallucinatory. And there’s no plot. Nothing happens in it until the last five minutes of every long act. So it doesn’t belong in an opera house. There’s nothing you can put on stage that’s in this music. I’d kind of been working on how to do this thing since I was 20. So then LA Phil stepped in and then we started discussing it…

Then there was this incredible moment where Bill asked for the text of the work, simply said thank you, shut the door, and two years later returned with this film. And I do not know what he went through. I visited one set for an hour, but I was not there for any of the shoots; I was not there as he sketched it out; I was not there for any of it. And the first time that I finally began to realize what he was doing or what his process was, was just last weekend when I went and read the notebooks he had kept while he made it. But until last weekend, I did not know anything! But again, Tristan exists on all these different planes independently, which is so satisfying. The music is independent, the images are independent, what the performers are doing… but there are these places where all the edges meet for a moment before they move off in their own directions. What happens is you’re taking the piece in on these different levels separately. You’re taking the words in, the images, the music — and all of these things are happening simultaneously, but also independently. It’s real to the time we live in, how everything is happening simultaneously, but not necessarily in synchronicity — and the contradictions are as interesting as the consequences.

And what Wagner is doing in the orchestra is always playing out characters’ memories. So while somebody is saying something, the orchestra is giving you what they’re remembering while they’re saying it. And so you’re constantly living in this intensely, deeply layered memory space. The beautiful thing about Bill’s images is that while they are not illustrating Wagner at all, when he was making this, he really was trying to take every image in the text and come up with his own emotional response to it. For Bill, the suffering of a naked tree in winter, in the harsh sunlight and the freezing day… It’s very specific. And Bill goes there and it’s all in his notebooks. He’s thinking about how winter turns into spring, about how something dying lives again — and he’s thinking of what that tree had to go through to get those first buds out.

Video still of Bill Viola, Fire Woman, from The Tristan Project

LAW: And from his studio up there on Signal Hill, he’s looking across the sea. There are ships on the horizon, but they’re not carrying beloveds home from Cornwall like in the story. They’re out there pumping oil into the ocean or some other mystery.

PS: The thing is, all that stuff is shot in Long Beach. That’s him. How does he feel sitting up on that hill watching the beach? And that’s his child, Blake, blowing out that match. And, you know, everything is so personal. Bill always has, you know, hired performers who look like him and dresses them like himself. And half of the people in the film are wearing [his partner] Kira [Perov]’s clothing. It’s all in the family, you know, and Isolde on film is wearing Bill’s mother’s cape that’s in Kira’s closet. So all these things are his memories. Just like in Tristan.

LAW: Bill’s work is often directly referencing Renaissance painting, but meanwhile, using technology to create another way of feeling, a new way to enter that painting and also go beyond it. It sounds like that’s the role of the work in terms of Wagner’s material as well.

Peter Sellars

PS: A lot of my own life is using the ancestors to look at ourselves and just say, Where are we when we’re next to this, and what does this make us notice — about what we became, or what we have yet to become? And does it make us realize that some things didn’t get better, other things probably got better, and some things got way worse? And meanwhile, what does it just mean to be human when you look at these other people who are asking the same questions? And so that is the continuity that Bill is deeply part of. And at the same time, he’s part of a generation that truly reinvented art because there were new materials. There was nothing like video before. It was not remotely like a film. It was a completely different experience, a completely different sense of time, of light, of fluidity — and we live in this world now.

This work insists that you engage with its meaning, as well as what we all feel every day, and yet don’t have the words for. This music takes you there and gives you the space to cry when you’re not allowed to cry in life. And it also gives you the space to just say, Oh, right, I’m not alone. And gradually Bill’s putting his own life into this in such a profound way — these things that we don’t have good words for because in our generation all these words turned into cliches. And we’re embarrassed to talk about it. Bill found imagery for what we’re all going through and that everybody’s seeing their therapist about and yet can’t be reduced to psychology — which is why you need mythology, religion, abstraction. You need all those other layers to get to it.

LAW: And I wonder, context is king in so many ways. Whose idea was it to stage this again? It’s really hard not to think about the last three years — people trapped in faraway lands, isolated, in exile. People racing to the deathbeds of their loved ones, only to not even be allowed into the building. I mean, that was real, and not that long ago, and it’s still happening…

PS: Let’s just say that being present at the creation of something is super exciting, but you have no idea what it is yet. And years later, you look at it again, you say, Oh. Oh, wow. And as the time-based part disappears, the part that reaches outside of time is what you’re living with. And then you realize the whole world is moving, and you realize that this piece saw that and got there before we did. And now you’re looking at something from 20 years ago that’s telling you what we’re feeling right now. And we didn’t have those feelings when it was new. We knew it was amazing, but we didn’t get what it really was about; we did not know that we would be living at this moment. But the artist was there. The artist is always in prophetic mode, the voice of clairvoyance, the voice of seeing clearly forward. And that’s Bill’s gift.

LAW: Well, I think this whole production is a kind of gift to people who, as you mentioned, are trying to work through it. Our culture has not prepared us for what is happening in the world. We have no understanding of what it means to talk about our emotions.

PS: And when you see Act One, Wagner knew that! Tristan can’t say a word! Yes, it’s all in this. It takes you into places that we’ve lost the keys for. But let’s please unlock that door and go ahead and open it — that is what the piece does.

The Tristan Project’s final series of three performances is Thursday-Saturday, December 15-17, at Disney Hall; laphil.org.

2007 LA Phil performance of The Tristan Project; video by Bill Viola

Video still of Bill Viola, Act III from The Tristan Project

Editor’s note: The disclaimer below refers to advertising posts and does not apply to this or any other editorial stories.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.