Reprinted from our sister paper The Village Voice, this exclusive interview with Abiodun Oyewole of the seminal collective The Last Poets is a must read for fans of hip hop and Black art. Warning: some might find the use of some language here offensive (namely the N word), but it serves a higher purpose in context of the profile and subject. As he explains here, the Poets’ intent was to elucidate America’s history of mistreatment of Black people with words and honest expression. Its goal was to dismantle the systems of oppression that held people of color back and inspire artists to speak out. They did that and so much more. — Ed.

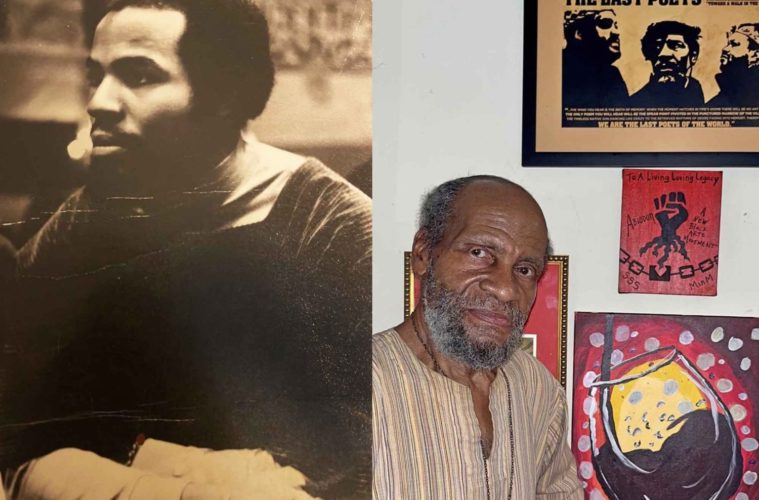

A founding member of the American music and spoken-word group The Last Poets, Abiodun Oyewole is also known as a founding father of hip hop. Public Enemy, A Tribe Called Quest, Wu-Tang Clan, Erykah Badu, and countless others cite The Last Poets as a major influence. “When The Revolution Comes,” from the Last Poets’ eponymous 1970 debut album, has been sampled in “Party and Bullshit,” by The Notorious B.I.G.; “Concerto in X Minor,” by Brand Nubian; and “Prolly,” by Sevyn Streeter, featuring Gucci Mane. Samples of “On the Subway,” from the same album, have been used by Digable Planets. The list goes on.

Oyewole was born Charles Davis, in Cincinnati, but grew up in Queens and regularly attended church in Harlem, a place of congregation, inspiration, and social measurement. His mother encouraged him to recite The Lord’s Prayer at such volume that he could be heard throughout the family home. Also inspiring was the poetry of Langston Hughes and his family’s gospel and jazz records. At 15, out of curiosity, Davis and a friend went to a Yoruban temple, in Harlem. There, the priest performed a ceremony and gave him the name Abiodun Oyewole.

Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated when Oyewole was 20 years old, and it had a profound impact on him. After the assassination, Oyewole, like many others, was outraged and wanted to take radical action—thanks to a friend and fellow poet, he was able to find positive, creative outlets of expression. As a child, Oyewole had also been made aware of Malcolm X, and heard that he was “telling the truth.” Malcolm X’s importance would eventually loom large for the poet.

The Last Poets began as a group when original members David Nelson and Oyewole shared their poems with each other. From that first album onward, they confronted listeners with volatile issues of the day, including urban decay, income inequality, and racism. The album’s first track is titled “Run Nigger,” and that word appears repeatedly throughout the work. The group’s stated intent was to elucidate America’s history of mistreatment of Black people, and ultimately to dismantle systems of oppression as well as to inspire and elevate Black communities. “When we said ‘Niggers’ we were not talking about a Black person; we were talking about a misguided, discombobulated human being,” says Oyewole. “Somebody who’s totally out of sorts, who does not know who he is, and has decided to take on ugly characteristics that should never have happened in the first place. But this is what some of us have been designed to be in America. It starts with hating yourself.”

Today, Oyewole, highly regarded as a poet, author, and teacher, feels conflicted about the way many hip hop artists have adopted the word “nigger” to represent a heroic figure, losing the revolutionary and ultimately edifying aim of The Last Poets’ message. But Oyewole persists—writing, making music, and inspiring generations of young creatives. With the help of his family, he released a new album, Gratitude, and on August 18 performed as part of Summerstage with Jamaaladeen Tacuma’s Band of Resistance and other acts, in Marcus Garvey Park, where The Last Poets had held their first performance, in 1968.

The Voice spoke with Oyewole about his background, the history of the group, and the enduring legacy of The Last Poets. (The interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

MC: What was influential for you on your path to becoming a poet?

AO: Women, without question, even from a young age. When I started writing poetry, I really started because I wanted to impress women. I guess I knew girls had some knowledge and wisdom that I wanted. Even though I couldn’t explain it as a child, as I got older, I realized it.

I’ve always marveled at women because they’ve navigated through life better than men. In many ways, men depend on their physical prowess to be somebody, and women don’t have that at their disposal, so they have to use other aspects. So poetry was a way for me to impress ladies. Even to this day, I try to do that.

As far I’m concerned, women are the motor of any culture, land, or place on the planet. They make everything happen. They give us their lives as a human race. Don’t mock women, praise her, love her, cherish her, protect her.

How did you first discover Malcolm X, and what did he mean to you?

I was raised in Queens, but we went to a Southern Baptist church in Harlem, on 108th Street between Central Park West and Manhattan Avenue, which was a joy for me. On Sundays, I didn’t have to do any work except clean the whitewall tires of my father’s Pontiac, which was light blue and white. I don’t know if you can imagine what that means. It was a serious status symbol, but they only work if the white of the tires is clean. My job was to make sure they were clean, with Brillo pads and soap. You can’t drive up to a church, which is really a social club, with dirty tires. Church is a status-seeking symbol situation. People looked at you, the way you were dressed, how you acted, to see how you were doing in life, and summarized everything going on just by how you looked in church. So, my father wanted to do church right.

We’d go to my father’s sister’s house—we called her Aunt Baby—after church. I remember I was sitting in the back seat, like I’d always sat, I was maybe 11 or 12. [From the car I saw] this man who looked orange, and he was taller than everyone else. I had no idea who he was. I remember my aunt saying to my mother, “They’re gonna kill that man because he’s telling the truth.” I wanted to jump into the conversation, but I was raised at a time when children were to be seen, not heard. I was thinking, “If I don’t tell the truth, I’m gonna get a whooping.” Telling the truth was a very important value, so it didn’t make sense to me. I was very confused. Anyway, a few years down the line, Malcolm X was assassinated. So I got a glimpse of him and heard what my aunt said, but I didn’t recognize his significance until later.

I went to Haaren High School, now called John Jay College. I’d come all the way from Queens. My homeroom teacher, Ms. Carpenter, was aware of who Malcolm was. He was killed on a Sunday; the following Monday she said, “He was a great man. You can all go home today.”

How did The Last Poets begin?

When they killed Dr. King, in 1968, I felt like I’d just been smacked in the face. They killed a man standing on a platform of peace, and they shot him down like a dog. I almost lost my mind.

That was a turning point in my life. I was working in an antipoverty program in East Harlem. The director, David Nelson, had the idea of creating a collective of poets to speak out about the problems of the day. He wanted at least three guys to give an example to Black people of how badly we needed to be unified, whether you were Muslim, Christian, whatever, and to show that the same foot was on all our necks. We both had that poetic thread in our veins. David told me we’d read poetry at a commemoration for Malcolm on May 19, 1968, in Marcus Garvey Park. [Malcolm X was born May 19, 1925.]

The director of recreation [at the antipoverty program], Michael Gorkin, was a Jewish guy. I was 18, and getting ready to go to school in Iowa. He offered me his apartment to crash in and on the table there was a book, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, by Alex Haley, with a note that said, “You ought to read this.” I was very grateful and motivated to the max, and shortly after, The Last Poets were born.

All of us young men at that time loved Malcolm and used poetry as our vehicle to express ourselves. We were like disciples of Malcolm. That was never more true than for The Last Poets. We were born on his birthday. I’ve always had reverence for him.

So Malcolm became a very central figure in my life, mainly because he stood up for the manhood of Black men. He made us recognize that we should never be less than who we’re supposed to be. It’s not gonna be handed to us naturally, it’s something that we have to demand. And I was with that. I was raised like that. Malcolm’s persona fit me perfectly. So The Last Poets was a part of the legacy of being raised in Queens by my workaholic father and my loving mother. All that gave me a basic foundation to love and appreciate Malcolm X.

I’ve read the book and agree, it’s great.

What’s so beautiful about it is that it takes you through the evolution of Malcolm X. I tell people all the time, having a revolution sounds nice, but we have to know what we want to do and be. We can’t just get rid of something without something to replace it. Before a revolution there has to be an evolution. Malcolm went through a bunch of different characters [Malcolm Little, Detroit Red, El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz] before he discovered himself as Malcolm X. And that’s different from Martin Luther King Jr., who was born with a silver spoon in his mouth. King’s mother was a teacher, and his father was a preacher. I don’t think Martin ever experienced poverty.

He was on a different path.

Exactly.

I have the first Last Poets album. Tracks like “On The Subway” really tell a story and give a sense of the times and places and still feel very relevant today. How do you see the legacy of your work and its effect on other genres, including hip hop?

Generally, all poetry has a timeless factor because poetry usually comes from the truth. And all the poet does is try to embellish it with words that entertain the imagination, so that truth does not dwindle. It’s actually magnified through the poet’s eyes, and that’s really all we tried to do. And the truth we tried to magnify and bring forth was the experience of Black people, something that Langston Hughes was superior at doing. But Langston Hughes didn’t have the revolutionary fervor that we came with.

We came with ideas of making changes. So we addressed the “Nigger.” The “Nigger” was a featured character in our work because we knew this was a creation that was harming us. We could not see the “Nigger” as somebody that you should champion. The “Nigger” was a character created out of slavery. I discovered the original “Nigger” was really a hybrid animal created to help the slaves on the plantation, and that animal was a mule. And that was the nickname for the mule. The white man created the mule by breeding a horse with a donkey that could not reproduce himself. He also took the African man, a Mandingo, and stripped him of his name, language, everything. He has treated this human being just like a mule. So in both cases, the mule and this human being are property of the master. Therefore he can call the mule “Nigger” and this Black man on two feet “Nigger.” So the word “Nigger” was used for the man and the animal. They were one and the same. They were both there to create wealth for him, to work for him. They were both his property.

We talked about that negative element of people who didn’t want to follow rules, could not organize, who wanted to tear things down with selfish behavior. We addressed that poison in the Black community. So I wrote a poem that went “Run nigger, run nigger. Get out of here. We don’t need you.” David wrote a poem that said, “Die Nigger, Nigger die.” Let the Black person emerge, stop being a “Nigger.” Gylan Kain had the greatest poem I’ve heard in my life dealing with the whole concept of “Niggers.” It was called “Niggers Are Untogether People.” It was a classic poem. He really breaks it down. One of his most riveting lines was “Niggers killed Malcolm. Fuck the CIA. Niggers held the guns.” You can’t get any more explicit than that. That’s clear.

The thing that bothers me about the influence of The Last Poets in hip hop is that there are so many artists who refer to “Nigger” as their best friend. “Nigger” has become the word that has captivated people around the world. We were in Rome a few years ago, in a nice hotel. I got up early to go out for a walk. I was standing in front of the building and some white boys say to each other, “Yo, what’s up nigger?” I said, “Oh my god, this is ridiculous!”

It’s used by everybody because hip hop has made the “Nigger” powerful and very, very famous. I know Chuck D, Nas, and Rakim, who don’t use it that much, but a lot of other cats do, and they ask, “Y’all use it, why can’t we?” If you listen to what we said, we said, “Yeah, but we didn’t say ‘Be it,’ we were saying, ‘Don’t be a Nigger,’ and now you’re embracing it as if it’s the only thing to be. That word has evolved. The hip hop world uses it as someone who’s a rebel, fighting against the system all the time. The “Nigger” is constantly a soldier against the system around him, and many people around the world identify with that character.

There are some things about hip hop I don’t agree with. I don’t like the fact that hip hop is sloppy. I don’t like that hip hop doesn’t respect its elders. It should, because if you’re lucky you’re gonna be an elder one day, and you’d like to be respected. I don’t agree with the look with pants hanging off your ass. I don’t like cursing and sloppy aspects. I’d like us to create in a positive way that makes life healthier and more meaningful. But we’ve gotten onto this path of creating without creating anything uplifting, and that’s not good.

This is a very pivotal time in the world, and hip hop drops some stuff that can put us on a favorable course. We have a lot of people dying not just from the virus but also from depression and not being able to socialize with each other. Hip hop can lead us into a place to help us grow. But instead, it talks about “bitches” and “hoes,” and all that bullshit, and that’s not working.

Hip hop artists like KRS1 and Public Enemy were very educational and inspirational, including for white people.

Right. Chuck D said, “Fight the Power.” That was directional stuff. That’s a revolutionary statement, whatever language you speak or culture you’re from. We know the government can be very oppressive. They don’t care who they oppress. You’ll get mashed down too, eventually.

What memories do you have of working with record producer Alan Douglas on the first album?

I had spoken with Jimi Hendrix, who had worked with Alan. I remember I didn’t want to be a recording artist. I wanted to be a revolutionary, using poetry like ammunition firing at the system. But our managers suggested it, so I went along with it. I didn’t want to go downtown to audition, so Alan came uptown and we auditioned for him at IS 201, on 128th, on the 2nd floor in a classroom. He said, “I’m ready to record anytime you are.”

The next time I saw him was down at Impact Sound recording studio. Side one was our first set, side two was our second set. That album is a one-take deal; there are no second takes, except for our conga player Nilaja, who laced it with different drums.

I remember I suggested putting our words on the inside cover of our first album so people could understand what we were saying. We were the first American band to do that—before us, only the Beatles had done that, with Sgt. Pepper.

What did you speak to Jimi Hendrix about?

He dug what we were doing, and said, “We gotta get something together,” and I said, “By all means.” He had the same revolutionary spirit that we had. So that door was open.

Later, Hendrix recorded with The Last Poets on “Doriella Du Fontaine.”

Yeah, with Jalal [a later member of The Last Poets]. But by that time, I had left. I didn’t have the patience I have now ’cause I was moving at light speed. Every month was like a year. The poetry and the accolades were not sufficient. I kept searching for something I could really latch onto.

I think my forte is being a teacher. That’s really where my strength lies, even today. I do have a passion for that. The thing that makes me feel my worth is imparting information to others and helping them find a way to develop their skills and crafts. I get the biggest thrill out of that.

Did you ever interact with The Watts Prophets?

We had a chance to do a gig together about 20 years ago, at a university in Los Angeles, California, that a professor had arranged. They said, “We started before you guys.” I said, ‘“So? Who wowed the crowd? You may have started before us, but nobody knew you.” They said, “OK, you got it!”

There was a little competition and rivalry, but we never let it get in the way. We respected each other. I was happy that we performed together. We even discussed recording, but that never happened.

There were no real groups that took off behind us. We didn’t have any competition from collectives of poets. No one could touch what we were doing at that time. We had a perfect formula with three poets and a conga player. When the first album came out, it sold well, which surprised Alan Douglas.

Can you tell me about current projects and your new album?

If I don’t have a project, I don’t feel like I’m living. In the last three years, I’ve been painting. My kids put them up on the walls. I guess I must be doing something cool. I do it because it’s therapeutic. It’s a different medium of expression and gives me a lot of joy. I think I’m improving. I’d be upset if I wasn’t. Whatever I do, I want it to be better. I want it to be great. I’m never really satisfied.

We ended up producing a phenomenal album called Gratitude. My family’s involved; I have a grandson who does tracks by computer. He does phenomenal stuff and has some special talent. Normally, I only work with real musicians and don’t do computer music. But he created some tracks that sounded interesting. My son Oba would suggest a track to go with a poem, and that’s how this album came to be. I’m very proud of the album. It’s a family project from A to Z. That’s why I love it.

I’m blown away by the magic of social media, but I’m not really into it. I haven’t bought, and refuse to buy, a cell phone. It’s less stressful without one. I have a wallet, and that’s all I’m concerned about keeping. I try to eliminate as much stress out of my life as possible.

What keeps you going?

The way I was raised has a lot to do with it. Having the right parents, the right people, and having an optimistic look on life because we all have to overcome difficult things. How you manage those moments determines who you really are. My reverence to my ancestors and the religious order that I believe in, Yoruba. My faith is strong, but that’s only because I’m willing to work as well. That’s allowed me to accomplish some things that I’m proud of.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.