When photographer Helmut Newton’s SUMO dropped 20 years ago it landed the only way a 464-page, 78-pound book could land: with a thud, but that didn’t stop it from becoming a monumental limited edition. Mostly black-and-white nude photos published by Taschen and released at Art Basel in 1999, it sold only 10,000 copies, each signed by the artist and accompanied by a metal stand by French designer Philippe Starck. SUMO was a landmark in the art book market and set a record a year later as the most expensive book of the 20th century when a copy signed by the models and artists pictured on its pages sold for $430,000 at a charity auction.

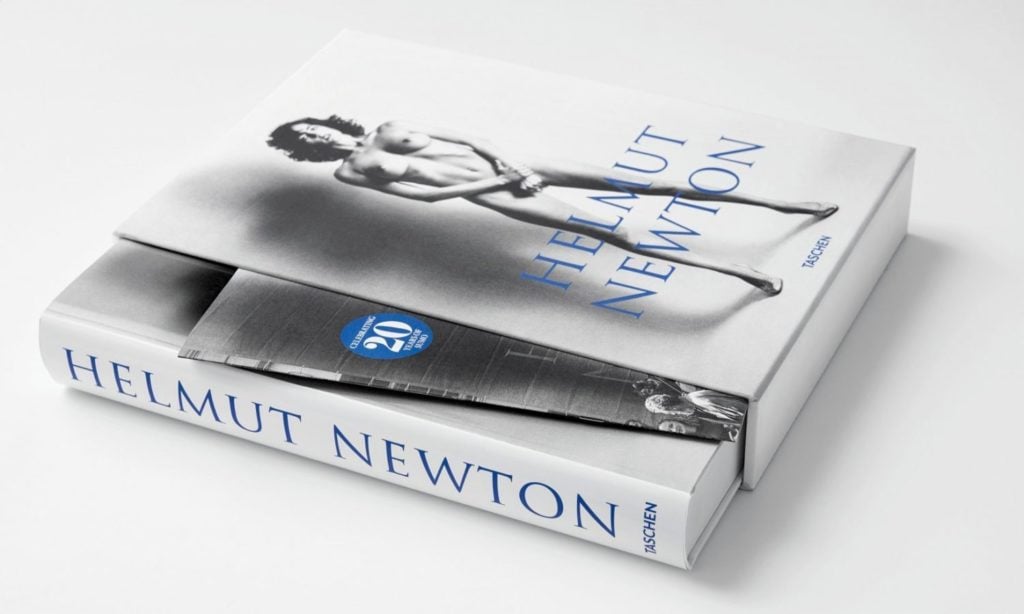

Now, 20 years later, Taschen reminds us what all the fuss was about with an anniversary edition of SUMO, a collection of museum-sized prints bound and elegantly packaged in a monochrome casing with one of Newton’s Giant Nudes on the cover, a hint at the arresting selection of silver, pearl and shadow-toned captures within. Shrunken from the unwieldy original, it still adds 12 pounds to your bookshelf, while lightening your wallet by only $150.

A journeyman photographer until the age of 40, Helmut Newton became “Newton” beginning in 1961, when he took a job with Vogue Paris, a partnership that would last into the late 1980s. The shots are characterized by casually naked or partially nude elegant women in public places, their blasé attitude daring viewers to be shocked.

Many seem empowered by their brazenness, but over time they begin to appear as objects. A paean to luxurious debauchery, the collection includes women that are almost invariably white, young and statuesque — a Playboy model in vintage dress, her shirt open exposing epic artificial enhancement, exits Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis house toward an awaiting sports car.

Helmit Newton’s SUMO 20th Anniversary Edition (TASCHEN)

Fetishism becomes a thing; nudes with plaster casts and body braces. From 1976, Saddle shows a woman in black bra and riding pants and boots, crouched on all fours on a bed with a saddle on her back. In 1980, Newton moves into the studio, beginning his Big Nudes series, which lasts until 1993. Inspired by German police photos of the radical Baader-Meinhof gang, the series features full-length imposing tableaux of nude subjects. The Naked and Dressed series juxtaposes two tableaux of models, both posed exactly the same, one side clothed, the other without. Domestic Nudes, photographed in Los Angeles in the 1980s, features lithe and graceful bodies next to refrigerators, stoves and washing machines.

In Date Rape, from 1991, a nude woman is taken from behind, her attacker’s hands covering her face. On the Beach, from 1996, shows the truncated remains of a nude woman in a garbage bag on a rocky shore. No matter how lovingly and tastefully rendered his subjects, politically correct, Newton is not. “The term ‘political correctness’ has always appalled me, reminding me of Orwell’s Thought Police and fascist regimes,” he writes in SUMO’s brief autobiographical intro.

Born in Berlin in 1920, Newton (changed from Neustädter after he became a British citizen in 1945), grew up Jewish during the rise of the Nazis. By the time he was 16, he decided to become a photographer and, through his mother, was apprenticed for two years to Yva (Else Ernestine Neuländer-Simon), an innovative photographer of the period. In the book’s text, Newton credits 1930s nighttime shots of Paris prostitutes by photographers Erich Salomon and Brassaï for the look he later brought to Vogue Paris.

Often more compelling than his nudes are Newton’s portraits, like the one of Catherine Deneuve, a cigarette dangling from her lip, manicured nails tugging at her bra line. In an antic composition embodying Twiggy’s spritely ’60s pop appeal, the fashion icon is caught mid-leap with a kitten collaged beside her. Around her is an apartment empty but for a white telephone on the floor and a black-and-white TV showing an episode of Batman. At Cannes in 1976, Isabelle Huppert is captured without makeup, her terry cloth robe falling from her shoulders, her face a mask of freckles.

(TASCHEN)

Andy Warhol appears dead as he sleeps in a 1974 portrait, hands folded resting on his black-leather jacketed chest. Anjelica Huston, with eyes whited out like some proto-punk Modigliani, casts a striking image, though not as chilling as Salvador Dali in 1986, three years before his death, eyes wide, mouth agape, reclining in a silk robe with a tube up his nose.

A color portrait taken in 1997 in L.A. shows David Hockney at his easel, grimacing while a painting of sunflowers before him reflects the real-life specimens around him. When asked, “What people do you like to photograph?” Newton was fond of answering, “Those I love, those I admire and those I hate.”

While shooting the Domestic Nudes series, the photographer and his wife, June, resided at legendary Chateau Marmont in West Hollywood, and happened to be staying there in the late 1990s when publisher Benedikt Taschen pitched them on the idea of SUMO. It’s also where Newton was in a fatal car accident on January 23, 2004, dying soon after at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. His ashes are buried three plots down from Marlene Dietrich’s final resting place at the Städtischer Friedhof III in Berlin.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.