In an earlier article, we discussed five common challenges family caregivers may encounter and how to cope with them. Of all caregiving types, caring for a person with dementia is, perhaps, the most difficult because, apart from the physical and emotional stressors, family dementia caregivers are constantly processing the loss of someone they once knew and no longer remembering who the caregiver is anymore. The feelings of developing estrangement and constant disconnect can frustrate both parties, resulting in even higher levels of caregiver burden. Dementia caregivers are grieving the loss of a loved one while they are still caring for them throughout the course of the disease. Click here to see the stages of dementia.

For most people, dementia means Alzheimer’s disease. It is true that Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia, but, based on the definition offered by the National Institute of Aging (NIA), dementia is a broad term presenting a range of symptoms that are associated with deterioration in memory and thinking abilities severe enough to diminish one’s ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). Understanding the differences among these types of dementia supplies insights into designing person-centered approaches to family caregiving.

Source: Alzheimer’s Association

Alzheimer’s Disease. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, it is a progressive cognitive impairment which accounts for 60-80% of dementia cases. As it develops slowly, it is not easy to be detected when a person is at the early stage of Alzheimer’s disease. In many cases, family members do not realize that their care receivers may have Alzheimer’s disease until patients display the symptoms, such as incapability to complete familiar tasks, difficulty in recognizing family members, personality changes, etc.

Vascular Dementia. Accounting for 10-20% of dementia cases, vascular dementia is the second most prevalent dementia type. It may result from a stroke or a series of small strokes. The rupture of a blood vessel in the brain may result in dementia occurring without other warning symptoms.

Lewy Body Dementia. Considered to be the third most common dementia type, Lewy body dementia occurs because of the disorder of certain proteins in a patient’s brain. It is progressive and can cause hallucination or delirium. Sometimes, it will change sleeping patterns so it may become easier for patients to sleep in daytime but difficult to sleep at night.

Frontotemporal Dementia. This form of dementia is caused by neuron loss in frontal and temporal lobes. Abnormal behaviors, emotional problems, difficulty in movements will gradually develop over time due changes in brain functioning.

Younger Onset Dementia. Although most dementia cases happen to older adults, it is not exclusive to them. For people who develop dementia at a younger age, genetics is often a factor with an existing family history.

Taking care of someone with dementia is not only about helping a person easily forgets and is compromised in communicating thoughts. As we can see from the definition, the cognition impairment can always affect a patient’s daily activities. It is both physically demanding and psychological demanding to caregivers because in the meantime of helping patients to survive, they need to bear the embarrassing moments brought by care receivers’ aberrant behavior.

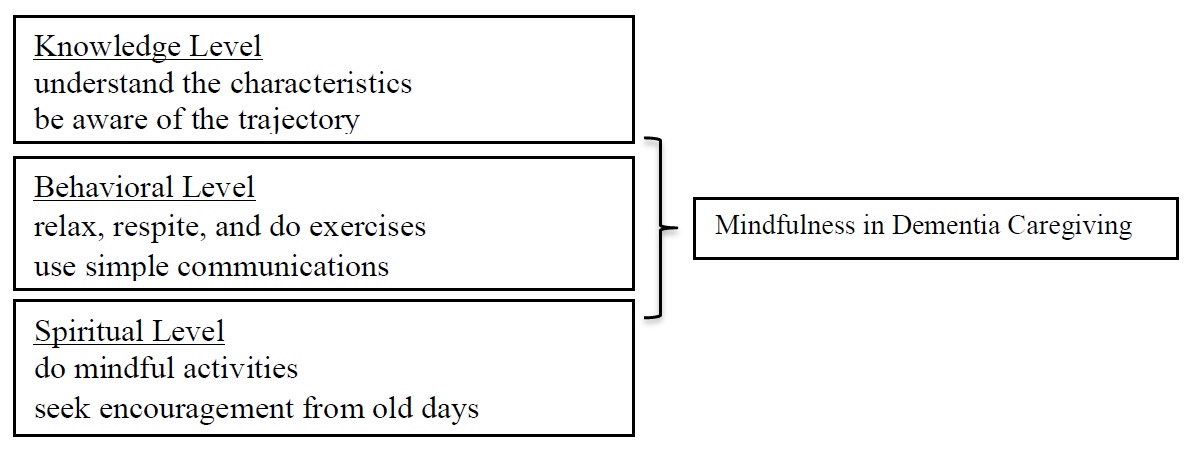

For instance, after receiving loving care, a dementia patient may not realize what has happened, and not only fail to express thankfulness, but instead, blame the caregiver resulting in feelings of powerlessness on both sides. So, how does one cope with the challenges of dementia caregiving? The literature suggests that family caregivers can mitigate some of the unique demands of family dementia caregiving by recognizing the outcomes of caregiving as an amalgamation of knowledge, behavioral, and spiritual perspectives.

Knowledge. The literature suggests that caregivers build a knowledge base of the specific dementia type involved. With a better understanding of the symptoms, characteristics, and trajectory of the disease, the non-normal activities of the dementia patient, for example, can be identified and enable caregivers to predict aberrant behavior of the care recipient.

Behavioral. The literature suggests that caregivers enhance their physical resilience through exercises and periodic respite. Since taking care of dementia patients is emotionally and physically challenging, with a healthy body, caregivers can be better equipped to undertake the work and improve their own quality of life. In terms of communication, in considering the care recipient’s cognitive impairment, we suggest caregivers use simple and clear phrases to achieve effective bi-directional communication.

Spiritual. The literature suggests that caregivers should seek some kind of emotional help, such as Mindfulness virtual workshops, e.g., as offered online from USC, to dismiss negative emotions resulting from the caregiving experience. Additionally, both family caregivers and care recipients may relive pleasant memories as a source of encouragement and motivation to mitigate the possibility of experiencing unintended communication or behavior that is physical or mentally abusive for all involved.

Caregiving is arduous, and dementia caregiving presents even more demands; remember, all caregivers deserve care themselves. If you are a caregiver in LA, please check the intervention programs offered by the USC Family Caregiver Support Center and the LA Alzheimer’s Savvy Caregiver Program. Each program is targeted to help family caregivers support their quality of life and manage all their responsibilities. .

There are many resources for caregivers and individuals with the diagnosis and be empowered that you are not alone. Governor Newsom has commissioned leaders in the field of Aging and Disability to tackle these vary issues for California’s Master Plan on Aging. The Master Plan on Aging proposal is expected to be released in early December.

If you need further information or wish to comment, please contact the authors at doctorgeorgeshannon@gmail.com. Be sure to leave your contact information.

George Shannon, MSG, PhD, Director: Rongxiang Xu Regenerative Life Sciences Lab (RxX Lab); Mengzhao Yan, MA; Erin Crutcher, MSG Candidate; Research Assistants, RxX Lab; USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.