Kate Braverman emerged during a time when much of contemporary writing was flat, disaffected and colorless. With her palpably lush and violently florid imagery, she was anything but a minimalist, and her bracingly evocative descriptions, caustic dialogue, often-outrageous characters and archly withering worldview would have stood out in any era.

The writing of the longtime Los Angeles poet-novelist, who died at age 70 in her sleep at home in Santa Fe, New Mexico, on Saturday, October 12, 2019, was often overshadowed by that of her celebrated students who went on to wider attention. You can hear traces of Kate’s poetic nihilism in the songs of the punk band X, and iconic local novelist Janet Fitch (White Oleander) has long acknowledged the transformative influence of her former teacher, but Braverman remains one of Los Angeles’ boldest and most strikingly original literary figures.

“Her work was so beautiful,” Fitch marvels in a phone interview. “She really cared about the beauty of language, the sheer magic of language … She had a furious commitment to excellence. If it wasn’t excellent, it was garbage.”

Fitch, poet Laurel Ann Bogen and actor-writer Joshua John Miller have assembled a free tribute to Braverman on Saturday, February 8, 8 p.m., at Beyond Baroque, the Westside literary arts center where Kate was a member of the Venice Poetry Workshop in the mid-1970s and helped shape the embryonic poetry and lyrics of X’s John Doe and Exene Cervenka, among others. Bogen, Fitch and Miller will read at the tribute, along with some of Braverman’s peers and former students, including Bill Mohr, Sandra Tsing Loh, L.A. Times columnist Patt Morrison, Michael C. Ford, Samantha Dunn, Rochelle Low, Harry Northup, James Cushing, Danielle Roter, Suzanne Lummis, Amy Scholder, Rita Williams, Nancy Spiller and Steven Reigns. Other additions to the bill include Michael Silverblatt, Linda Venis, Rod Bradley and B.J. Robbins.

Braverman was championed early on by Joan Didion and John Rechy, and, like Didion, she observed the world around her with a sardonic, all-seeing and remorselessly unsentimental intensity. While Didion can appear at a distant remove, Braverman was always more dramatic and overtly passionate. “I have stuck needles/in the sides of the poem,/and made the poem live/without sleep or love or hope,” she declared in “Summer Poem,” from her 1977 poetry collection, Milk Run.

Like Sylvia Plath, Braverman could distill a sense of existential dread and alienation into a few exactingly carved, icily chilling details. But whereas the heroine of Plath’s classic semiautobiographical novel, The Bell Jar, is kind of a hopeless square, the narrator of Braverman’s startling semiautobiographical 1979 debut novel, Lithium for Medea, shoots up cocaine and engages in a sexually sadistic relationship with her boyfriend amid the ruins of pre-gentrified Venice. Lithium is far more punk rock in attitude than the empty calories of Brett Easton Ellis’ Less Than Zero, which made a bigger splash six years later, and it was powered by an unrelentingly fierce poetic acuity and feminist-informed intensity that transcended the Beats’ relatively quaint attempts to describe sex and drugs.

“Kate Braverman knew darkness, and it didn’t scare her,” X singer-bassist John Doe wrote in an email to the Weekly shortly after Braverman’s death. “She was punk before there were punks. Her visionary writing and sharp wit put her in her own class. She led the way for those coming up behind her. An empty place at the table will be set for her forever.”

“She was my friend, a unique friend, a unique person — and, yes, I can say this: She was a great writer, sadly unrecognized,” John Rechy writes. “I hope she will be, eventually. She had a prose style that was passionate, at times sorrowful, at times elated, yes, grandly manic, always beautiful. That was so, too, of her rich poetry. Truly, it is an indictment of the vast and mean indifference, and ignorance, with which some artists are treated that her work was not celebrated as it deserved and deserves.”

“I had been a fan for a long time because of Lithium for Medea and Lullaby for Sinners [Braverman’s 1980 poetry collection],” Fitch says. “I saw her at Small World bookstore in Venice on the boardwalk. She was reading from Palm Latitudes. I was crazy about her and said I would love to work with her. I knew that she did teach privately. She had two workshops. In the morning, they brought in Danish, and in the afternoon they brought in their egos. I was in the afternoon workshop for two years at her home in Beverly Hills on Palm Drive, on a street lined with jacaranda trees, a gift from the universe for trying so hard.”

“I remember being carried away by Palm Latitudes, so dense and beautifully written,” Fitch explains about Braverman’s L.A.-centric 1988 novel about a trio of Latina women. She also cites some of Braverman’s stories in the 1990 collection Squandering the Blue as among her favorites. “I loved ‘Tall Tales From the Mekong Delta,’” Fitch says. “The Incantation of Frida K. [Braverman’s 2002 fantasy about Frida Kahlo] was uneven, but when she was hitting it, it was brilliant … Kate’s unabashedly romantic language, the lushness of that prose, the flight of imagination — that changed my writing and really marked it.”

Recalling Braverman’s workshops — which over the years included such notable students as Donald Rawley, Samantha Dunn, Jordan Gallader, Les Plesko, Cristina García, Joshua John Miller and Mary Rakow — Fitch says, “It was an intense experience. It was like an apprenticeship, a trial by fire. I came to her because I’d gotten as far I could on my own — what I was missing was the music.”

“She called me ‘the honorable schoolgirl,’ which is funny,” Fitch continues. “I was the good girl who could be relied upon … It was a complex relationship … ‘Oh, you could make a good living as a romance writer,’” Fitch remembers Braverman saying about one of her pieces. “I sat out under the jacarandas and wept. When she liked something you did, you were praised to the skies. She was on a float throwing Mardi Gras beads … She was brilliant, funny. She thought mediocrity was evil. She was always pushing you, pushing you for something better — ‘What’d you do? Fax that in?’ There’s no such thing as a good-enough sentence; it’s either beautiful or it’s not … But I picked up a tremendous amount as a teacher,” Fitch adds. “When I lead workshops, I do it in a similar way to her. You learn a lot by reading it out loud. It really trains the editorial eyes and ears.”

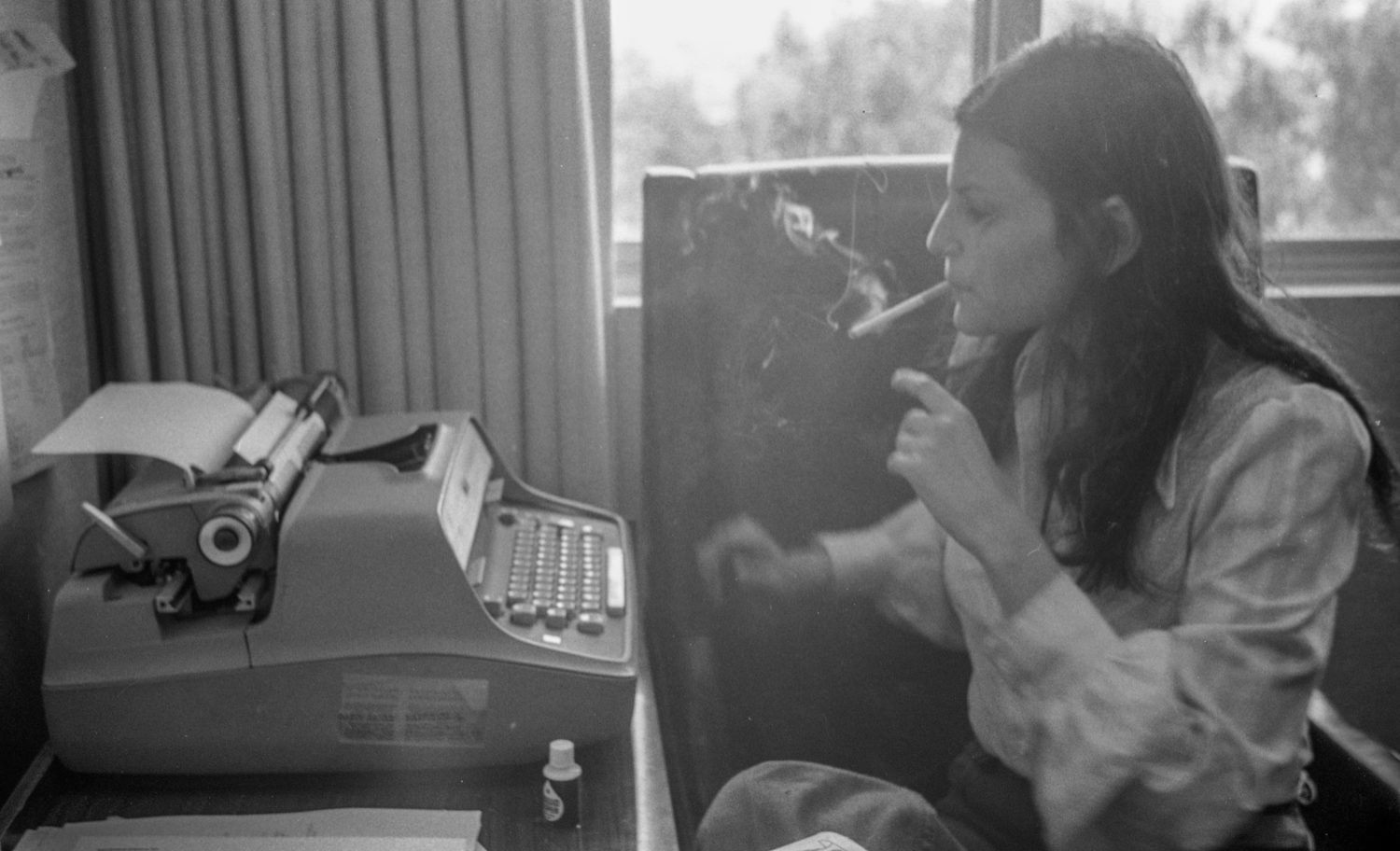

Kate Braverman (photo by Rod Bradley)

“The most famous Kate-quote moment … is when our writing for that session didn’t measure up, she’d take off her reading glasses, hold them on her lap and say with visible disdain, ‘This … is a crime against the page!’” novelist Mary Rakow (The Memory Room) writes. “I think we all recognize her interest in us was not personal. And she could be cruel. But it was for something greater than each of us … It was about literature itself, as one of the few but powerful inventions of our culture that can actually save us … Her other most basic advice, startling to me when we first heard it, was ‘Write toward the pain.’ A very freeing invitation since many workshops are little more than feel-good, patty-cake gatherings. No. Write toward the pain … In the pain of our lives, if we honor it by the gift of a sustained attentiveness, and so bring it onto the page, that pain both in us and in our readers through empathy has a chance to become something else.”

Writer Samantha Dunn (Faith in Carlos Gomez: A Memoir of Salsa, Sex and Salvation) also recalls Kate railing about “the unpardonable sin of a cliché or just a boring sentence” and describing most writing as “a crime against the page.” She writes, “The first time I heard anything about Kate Braverman was in the early 1990s. I had been in Los Angeles only a couple of years. On a weekday morning like any other, I was driving on the Ventura Freeway to a crummy job at a trade-magazine publishing joint in Van Nuys. I switched on NPR, and out of the speakers comes this growling-whispering voice of a woman talking about writing in a way I didn’t even know was possible. It was like the first time I heard Patti Smith singing ‘Gloria.’ Like, I didn’t know we were allowed to do that. The interviewer asked her the trite ‘what are your influences’ question, and instead of rattling off the usual literary lions, she said, ‘The pulse of rock & roll.’ She put Jim Morrison on the same pedestal as Chekhov, as Bellow. That was it. The die was cast; wherever this woman was, I had to go. The interview mentioned that she taught at UCLA Extension, so when I got to said crummy job, I went to the phone book (that’s how long ago it was), called UCLA and enrolled in the next weekend class I could … I spent I think three years in her private group, and I wrote most of what would be my first novel, Failing Paris. And I met the people who would form the core of my life.”

“God, there’s so much to tell,” Dunn writes. “It didn’t end well. She could be so sadistic, so unfathomably cruel and self-serving. I didn’t speak to her for 20 years. But: What she imprinted on me was not only the fierce craving for language and stories that are necessary and dangerous to tell, the stuff she was famous for. What she … bestowed on me was permission to be a woman who didn’t apologize for who she was, a woman that didn’t have to be pleasant all the time.”

“I think Janet Fitch accurately described her as a ‘high priestess of literature,’” writes Gabrielle Goldstein, Braverman’s daughter. “A priestess officiates in sacred rites but also serves the spiritual needs of the community. Kate’s writing was an alchemical gift. And she was also a teacher and mentor whose classes and private workshops birthed and nurtured literary careers and friendships, many of which endure to this day. In her life and in her art, she was uncompromising and complex. She was a feminist, a punk rocker, a poet. She loved the Sisters of Mercy and Leonard Cohen in equal measure. It’s true that she was a goth gypsy in black velvet and bangles. But she could also have a prankster’s light humor, and her laugh was silvery and musical. She loved, and lived, and wrote, with untamable intensity.”

“She was so intensely nuanced, always writing in fevered white heat,” poet Jordan Gallader rhapsodized after her former mentor passed away. “Her prose and poetry fit her persona — lyrical and lurid, an instantaneous convulsion of palm trees seared against a Los Angeles skyline she loathed and simultaneously embraced. My friend, my sister, my anti-heroine, your words are forever seared like this blistering city against that squandering blue.”

“Kate liked to think of herself as a bold literary outlaw,” writes Braverman’s longtime friend and photographer Rod Bradley. “And on paper, she was. In life, she tried to follow suit, and it got her in lots of hot water she was helpless to get out of, although it did provide her with more than sufficient motivation to get back to the one place she felt she had control of things. Writing was her consolation … She was in essence, in my mind, always a poet even when working as a novelist and writer of stories. And while the tribulations of her life buffeted her, she somehow maintained, despite her raw, cynical darkness and despair, a kind of childlike innocence, that astonishment that brought her writing to life and astonished her discreet readers.”

Chicano activist, writer and musician Rubén Guevara (Ruben & the Jets) writes about his relationship with Braverman in the 1980s: “Behind the fierce façade and outrageous persona was a frightened and secretly vulnerable child who desperately wanted to love, and to be loved, but couldn’t figure out how to do it. Consequently, writing became her lover, refuge, sanctuary and salvation. Our spoken-word collaborations as The Lady & the Lowrider at various theaters, cultural centers and universities, with Con Safos backing her, went surprisingly well. She loved reading with a band. In closing, she inspired me to become a better writer — to stretch out into new terrain with a new lexicon — and for that, I’m forever grateful.”

“She was the most gifted of all of us in terms of having nimble access to an imagination overbrimming with lyricism. To this day, I don’t believe I have ever met anyone who is as gifted as she was,” Bill Mohr wrote on his blog (billmohrpoet.com) after Braverman died. Mohr was part of the Venice Poetry Workshop at Beyond Baroque and published Braverman’s first poetry collection, Milk Run, on his Momentum Press. “She saw no reason to compromise, at least when she was young, and why should she change? Writing sentences that oozed the scintillating excesses of color’s exquisitely warped reverberations was all she ever cared about. If you didn’t want to dance to it, then take your drum kit somewhere else. She didn’t need you to tune her guitar.”

Kate Braverman (photo by Rod Bradley)

Full disclosure: I was also a member of Braverman’s workshops in the 1980s and remember her fervent intensity about language and the way she would strip clichés and prosaic prose from her students’ raw poems and boil them down to their essence. It wasn’t enough, for instance, to write that two characters were talking together in a room. Every detail of that room had to be wrung out and arrayed, along with every smell, every sight, every expression, every sound. Nor was it enough to describe an outdoor setting without delineating specifically and clearly the color and type of every plant and animal.

Braverman used to hand out color charts and lists with the many names of flowers to improve her students’ sense of details. She exhorted her students to walk around their own neighborhoods with notebooks, like hunters, stalking every mundane street and alley while looking for signs of life, hints of something out of the ordinary, as they took possession of their worlds with words.

As much as Braverman reveled in florid imagery, she insisted that poetry wasn’t about painting pretty pictures. She reminded that the best way to instantly turn a sappy, sentimental phrase into real art was to put the word “no” in front of it — a very punk-rock mentality. In the early days of the workshop, which started as a UCLA Extension class at a church in Westwood before she relocated the gatherings to her home in Beverly Hills, Braverman preached an ascetic, extreme lifestyle and gave her students a series of rules to improve their focus and discipline.

Braverman lectured us to never eat lunch, as she believed that it wasn’t a real meal and would only slow us down. Nor were we to watch television, as it was a boring distraction that drained energy from the more important calling of writing. She forbade us to share new poems and short stories with our significant others, friends and relatives, as their opinions and mixed motives would only cloud the purity of our art. Braverman also admonished us to not pollute our minds with drugs or drinking as she was in the midst of a fanatically healthy lifestyle, although the teacher would stray from her own advice in later years.

Throughout her life, even after the Philadelphia native eventually left California and relocated to New Mexico, Braverman continued to write, releasing such idiosyncratic works as Frantic Transmissions to and From Los Angeles: An Accidental Memoir (2006), the poetry roundup Postcard From August (1990), and a short-story collection, Small Craft Warnings. Her last compilation of short stories, A Good Day for Seppuku, was published in 2018 by City Lights Books. That final book is suffused with such distinctive passages as “The forest is an inland sea with wind currents the texture of waves … The forest is an engine, a wind-fueled orchestra.”

In the story “Women of the Ports,” Braverman advises that “Emotions have their own inexplicable currents and random lightning storms” and that “Midnight currents are actually leaves brushing the ocean with russet and amber. Waves answer to the moon and immutable laws of spin and fall.” Even amid such beauty, Braverman warns, “There’s a certain pause just before sunset when the bay is veiled in azure. It’s the moment for redemption or drowning.”

In the book’s title story, Braverman could be anticipating her own absence: “The dead and the missing exert a field that doesn’t dissipate. Gestures and phrases have half-lives. Silences are deserted plazas, dusty, throttled by wind where the last goat starves. Omissions are a dereliction.”

Omission and self-censorship were perhaps the worst sins of all, so Kate Braverman never left anything out.

“A Tribute to Kate Braverman” takes place at Beyond Baroque, 681 Venice Blvd., Venice; Sat., Feb. 8, 8 p.m.; free, donations welcome. (310) 822-3006, www.beyondbaroque.org.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.