In the Before Times, the ephemeral, solitary majesty of Andy Goldsworthy’s disappearing monuments offered a counterpoint to the culture of economics, materiality, permanence, control, waste, and rush. He’s known for the kind of slow, attentive, site-specific object creations such as were witnessed in the iconic documentary Rivers and Tides, in which he scavenges and gathers found bits of nature — twigs, leaves, stones, feathers, moss, driftwood — and transforms them into stacked, woven, layered works that are then left to fly, float, or fade away with the elements.

So, what happens when an artist known for working with what’s in arm’s reach finds himself in lockdown at home along with the rest of a pandemic-afflicted planet? Well, if he happens to live among rolling hills and fields littered with sheep’s wool, leaves, and feathers, with rain-soaked earth and sheds that need sweeping, then that’s what he will work with. In the year of pandemic, Goldsworthy’s almost monastic performative practice has become something absolutely emblematic of a world plunged into solitude. Rooted in honoring the earth’s inherent gifts and the rich rewards of attentiveness to one’s immediate surroundings, Goldsworthy digs deeper into suddenly even more salient strategies for reshaping our relationship with time from one of struggle to one of collaboration.

Andy Goldsworthy, Wet wool drawing waterfall. Dumfriesshire, Scotland. 14 June 2020 (Courtesy of Matthew Brown Los Angeles)

The current exhibition at Matthew Brown Los Angeles includes photographs and video works documenting a series of temporary sculptural actions, as well as related and marginally more archival sculptures from the projects, all made in 2020, and all undertaken at or within walking distance of his home in Scotland. The presentation includes both works made of field-gathered objects, interventions into the surrounding acres of bucolic landscape, and ritualistic movement-based works interacting with the site’s feral architecture and local weather patterns.

The pieces most recognizable to fans of the artist’s work are the loosely woven woolen lane gate, installed and photographed at sunrise and sunset, its glistening, dewy, backlit aura making the mundane magical and prefiguring the inevitable dissolution of its fuzzy geometry. The “wet drawing” in which raw wool is clunkily unspooled down a waterfall is both ambitious and a little absurd, such effort expended for a half-life of dissonance and lowkey, organic surrealism. The radiant and perfectly imperfect spheres made of shiny, spectral, inky crow feathers and frazzled, vivacious, wig-like wool are each both charming and bizarre, and speak poignantly to Goldsworthy’s essential aesthetic of minimal manipulation of his naturally occurring materials.

Andy Goldsworthy, Crow. Sheep. Hand. Dumfriesshire, Scotland. July 2020 (Courtesy of Matthew Brown Los Angeles)

The exhibition is accompanied by a substantial and rather moving statement from the artist on the circumstances of the exhibition’s making. “Like everyone else I am trying to work my way through the events of this year,” he writes. “The urge to create no matter what is not just a way of getting through but also fighting back. Art has the capacity and indeed the responsibility to be creative no matter what the circumstances or restrictions.” And truly there may be no artist better prepared to engage with and express the intimacy, immediacy, confined, close-to-home, close-at-hand quality of our shared isolation than Goldsworthy — and to elicit the poetry from within its melancholy.

One photograph and video series explores the broom-brushed patterns of a swept-up cow shed, another the artist’s adventures making shadows in rain atop its rusty corrugated roof. His physical interaction with this architecture both highlights and mitigates its harsh, assertively depopulated (except for him) and forlorn mood. When he covers the entire floor of his small office with shaggy found wool, including the random sprays of paint herders use to identify their flocks, it’s both hilarious and incredibly sad, inviting and repulsive, tactile and probably pungent.

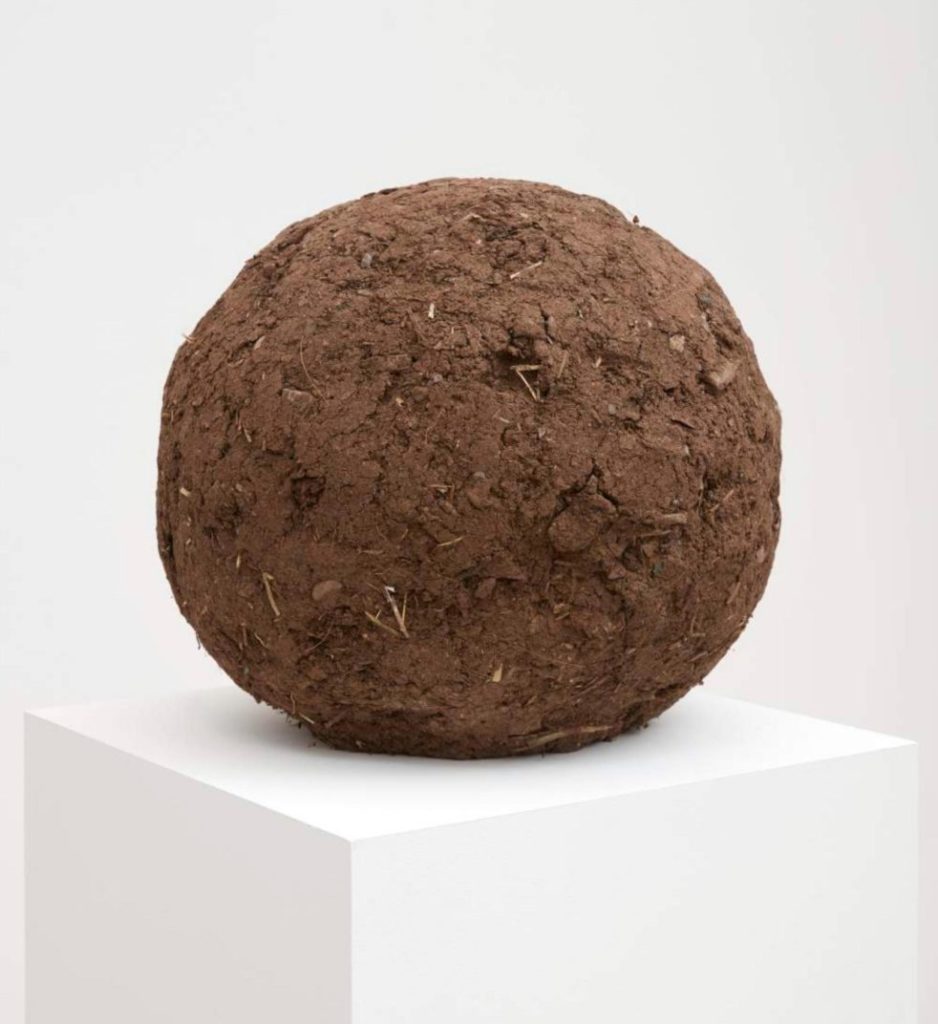

Andy Goldsworthy, Shed Stone. 2020, 2020, Rammed dirt (Courtesy of Matthew Brown Los Angeles)

The same is true of the large, perfect, hypnotic strangeness of the sphere of packed soil on a pedestal in the center of the room. The idea in this work and indeed across the entire show, and arguably his full career, is that the earth’s bounty provides more than enough inspiration and material for the artist, and that a work need not be permanent to be full of enduring meaning. Sometimes, it seems to say, we must let what we have in front of us be enough. Everything is in flux, what a blessing it is to find a way to roll with it.

Matthew Brown Los Angeles, 633 N. La Brea, Hollywood; open by appointment through December; matthewbrowngallery.com.

Andy Goldsworthy, Wool. Office in lockdown. Dumfriesshire, Scotland. 13 June 2020 (Courtesy of Matthew Brown Los Angeles)

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.