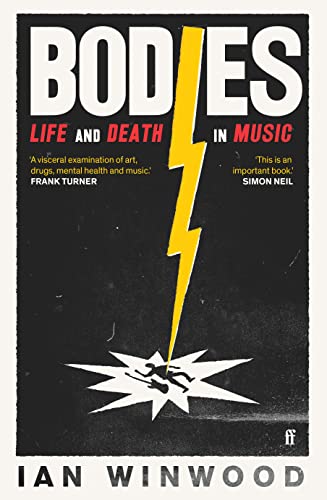

Ian Winwood’s Bodies: Life & Death In Music

British author and journalist Ian Winwood last appeared in the LA Weekly at the end of 2018 when he discussed his book Smash!, about the ’90s punk explosion. His latest work is Bodies: Life & Death In Music, an unflinching and often unflattering examination of the music industry. It’s getting a North American release this month via Faber, and Winwood has allowed us to print the introduction as a teaser.

I used to speak to my dad whenever I was at an airport. Standing on the pavement outside Heathrow or Gatwick, Stansted or City, I’d place a call to his small office just outside our hometown of Barnsley, in South Yorkshire.

‘Hello, Triple Engineering,’ he’d say.

To which I’d always reply, ‘Hello, Triple Engineering.’

‘Eyup, pal.’

‘How we doing?’

‘Fine. Fine.’

‘Another customary call from the airport, Dad.’

That’s what we called these brief exchanges of ours – a customary call from the airport. While Eric Winwood sat at his desk (in his slippers) estimating the cost of steelwork on construction projects tall and wide, down in the beautiful south his son was off to inter- view musicians on behalf of a national publication that paid him to do so. My father wasn’t much interested in the bands and artists to whom I spoke, or, as far as I could tell, in the stories I wrote about them. But he did get a kick out of me visiting cities that had been revealed to him in the pages of a book.

‘Where to this time?’ he’d ask.

‘New York, Dad.’

‘Oh, right – the City That Never Sleeps.’

This ‘oh’ would last for two or three beats.The ‘right’ would rhyme

with ‘eight’.

‘Chicago today, pal.’

‘Oh, the Windy City. Good stuff.’

From my father, ‘good stuff ’ was the highest praise.

‘Pacific Northwest, Dad. All the way to Seattle.’

‘Get in. Jet City.’

Eric knew the nickname of every place I went. San Francisco was

the City by the Bay. New Orleans was the Big Easy. Milwaukee was Brew City. I sometimes wondered just how deep this seam of knowledge ran. If I’d have phoned him from Gatwick with the news that I was headed to Pilot Butte, Saskatchewan, would he have said, ‘Now then,’ – nar then – ‘the Sand Capital of Canada’?

One Friday in summer I was bound for California with a record company press officer and an insufferable photographer. Like me, the pair were well used to spending vast swathes of the early twenty-first century in mid-air; unlike me, they seemed to regard this bounty of complimentary trans-global travel as a matter of cheerless mundanity. It gets worse. At Heathrow I learned that my companions had been gifted an upgrade to business class, while I – Muggins here, Mr Chopped Liver – remained at the rear of the plane. Estimating the scale of this injustice, with typical equanimity I judged it to be the worst thing that had ever happened.

‘Hello, Triple Engineering.’

‘Hello, Triple Engineering.’

‘Eyup, pal.’

‘A customary call from the airport.’ ‘Ooh . . .’

‘Los Angeles.’

‘City of Angels.’ A pause. ‘I must say, you don’t sound particularly happy about it . . .’

He didn’t miss much, my dad. A man of economical horizons, after leaving secondary modern at fifteen he inevitably followed his own father down the pit. Man and boy, a dawn chorus at Houghton Main Colliery. I remember him telling me that he hated every minute of his time underground. At a loss for a response, I asked for how long he’d stuck it out. Seven years, he said. Seven years? I don’t think I’d have made it to elevenses. To be honest with you, I’m not sure coalminers take elevenses.

In the hope of learning something new, each day after work he took a paperback to a quiet corner of a traditional pub on the outskirts of Barnsley. Widely respected as an erudite arbiter of ale- house disputes – a shout across the bar: ‘Eric! Who was it that wrote The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight?’ – he carried himself with an authoritative intelligence that was rarely impatient and never unkind. When he and my mother divorced he would send letters to my new home in the south of England. Deprived of the conventional bulwarks of physical comedy – gesture, intonation, facial expression – I used to marvel at his ability to bring forth laughter using only the words on the page.

Beneath a headstone that reads ‘Eric Ian Winwood: Son, Father, Brother, Friend – Mined from the Good Stuff,’ these days my dad is buried in a plot at Ardsley Cemetery. As well as giving me the gift of reading for pleasure, he bequeathed me a talent for placing words in an order that earns me my living.

Sometimes this living takes me to Los Angeles.

‘Well, I’m not very happy about it, Dad, to be honest with you.’ ‘Oh. Right. Why on earth not?’

So I told Eric of the egregious assault on my human rights.

Eleven hours cocooned with hundreds of other common-or-garden arse-scratchers in the cheap seats of an airborne dildo. ‘I’m right at the back,’ I told him. ‘Right next to the toilets. There’ll be coming and going and faffing about and bad smells and bad food and . . . all of that. And I wouldn’t mind, Dad, I really wouldn’t, but the people I’m travelling with have been upgraded, and, I mean, I’m not being funny or nothing but, well . . . well . . . they don’t even deserve it.’

A moment’s silence. A question dangling on a hook. ‘Do you know what I’m doing tonight, pal?’

I had no idea. The last film Eric saw at the pictures was Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984). A visit to a restaurant in town was by now an annual event.

Okay, I’ll play. ‘Dad, what are you doing tonight?’

‘Funny you should ask, son,’ he says. Oh, God, he’s starting his engines. ‘I’m heading into Barnsley for a couple of pints. And when I’m there, Ian, you’ll be in Los Angeles.’

‘Right.’

‘Right. So shut the fuck up.’

There were a number of things I didn’t share with my dad. I didn’t tell him that the music business tolerates – celebrates – terrifying behaviour. I didn’t divulge that after three days at the Reading Festival, his own stepson had remarked that the open-all-hours tomfoolery of me and my friends would have us sacked from any other line of work. When he asked me how things were going, I failed to mention that things were swerving out of control. A world of trouble was coming down the pipes. We didn’t yet know it, my dad and I, but a terrible storm was headed our way.

In time, medically qualified women and men will tell me that I have Rapid Cycling Bipolar Affective Disorder, Impulse Control Disorder, Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotional Dysregulation Disorder. I also have Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. From a stylistic point of view, that’s a lot ‘disorder’ for one paragraph. In starkly lit offices in Islington and Camden, I’ve explained my situation to at least two dozen therapists. I’ve taken so much medication that it’s likely I’ll be buried in a coffin with a childproof lid.

Divided in their diagnoses, the professionals agreed that I was gravely unwell. I’ve broken my bones and torn my flesh. Fearing me dead, the police have visited my home in the thick of the night. I’ve had the Old Bill in my back garden in the middle of the day. The purity of purpose with which I drove my needles into the red was a thing to behold; in a certain light, it looked like rage. Drugs, always drugs. Ablaze with paranoia, there were times when I was certain that an armed response unit sat waiting in the bushes in the back garden. I once moved so far from reality that I believed I was sharing my living room with a pair of kindly Nigerian strangers. Perched on the settee, I couldn’t believe how placid they were. Turns out they were my cats.

Today I’m relieved to report that I’ve been well for almost three years. But for the longest time, my behaviour was given perfect cover by the industry in which I work. Out here, there’s always plenty of company. Over the course of my career I’ve spoken with many scores of musicians whose behaviour might reasonably be described as deranged. Some are my acquaintances, and a number are my friends. I’ve written about people who, like me, have seen the insides of psychiatric care facilities. I’ve transcribed the words of performers who have since taken their own lives. Drink and drugs are everywhere. Like a magnet, the music business attracts people hardwired for self-destruction; as well as this, it provides an unsafe environment for those who might not otherwise give it a go. A perfect monster, it is both the chicken and the egg.

Scenting blood, I have written reams of articles that examine in precise detail the degradation of a hundred lives. I thrive on ruination. I will defend the tone of these pieces but I can hardly deny their existence; stacked up, they reach the height of a drum stool. In a luxurious apartment near Park Lane, Trent Reznor, of Nine Inch Nails, once told me of the time he was sectioned to a psychiatric institution after ingesting quantities of heroin and cocaine. Even as he spoke, I could hear trumpets in my ears. ‘That’s it, right there,’ I thought. ‘That’s my intro. The rest will write itself.’ And it was, and it did. Two days later the features editor at the New Musical Express told me it was my best piece yet.

I knew I was being played. I knew that Reznor wanted this story to appear in print. Selling the sizzle with screaming headlines and tales of horror, my trade offers a ringside seat for a circus at which the unlucky drop dead. People damaged beyond repair are eulogised as fallen heroes whose messy fates are largely unconnected to the dangerous terrain on which they practice their trade. Those who survive, or who seem to, will be written up as victors in a war whose rules of engagement are dangerously abstract. We never join the dots; working on a case-by-case basis, the full story is never told. So here goes. There is something systemically broken in the world of music. It’s making people ill.

This book is my attempt to join the dots. In writing this story I don’t wish to imply that people who work in other fields are unencumbered by mental illness or that their lives are spared the burden of addiction. As the twenty-first century approaches its first chorus, matters of the mind have become part of a mainstream conversation. Good. But there is, I think, something exceptional about our habit of romanticising the ghastly stories of my wing of the creative industries. Some of us are wedded to the idea that capable art should be underwritten by human suffering. Others bow to the image of the musician as an outlaw with license to do anything. When it comes to music played loud, this last one is particularly tenacious. How else to explain the ever increasing popularity of Mötley Crüe? It’s certainly no place for the faint of heart. Financially squeezed by a business model that has rendered recorded music all but worth- less, for all but the most popular bands the road is the only place from which an income is guaranteed. Out on tour you’ll find a dozen or more people living on a bus; its overworked residents run the risk of becoming co-dependent and infantilised. Brothers and sisters in arms, come the end of a tour they can barely stand the sight of one another. Believe me, I’ve seen ’em come and I’ve seen ’em go. If it is found at all, success can disappear in the space of a single album cycle. Bereft, artists are left to wonder what on earth just happened, or what they did wrong. (They did nothing wrong, or else everything.) Among them are people for whom a life in music is the only thing they’ve ever wanted. Going out of business in this

way is a shock from which some will never quite recover.

Starved of time for conventional relationships, out in the field musicians form bonds that are tenacious and unwise. Lars Ulrich, from Metallica, once noted that he could tell that his group were going places when, in favour of cheaper alternatives, concert promoters began stocking their dressing rooms with bottles of Absolut vodka. There can’t be many jobs that come with a free supply of hooch. Headline acts and support bands alike can be assured, upon request, of a backstage area stocked with crates of beer and bottles of wine and spirits. For those hoping to go off-piste, a discreet word in the right ear will secure refreshment in the form of pills and powders. In the music business, people who don’t take drugs are tolerant of those who do. Nobody’s against it. At its furthest remove, everybody knows somebody who knows somebody who can help.

So this is a book about all of that: about music, musicians, the industry, mental health, addiction, derangement, corrosive masculinity, monomania, overdoses, suicide and a hectare of early graves. Were he a bloodthirsty editor at a national publication, Eric Winwood would doubtless describe this as ‘the good stuff.’ As a journalist, I do too. But in writing this story, I’ve come to regard artists as victims and survivors of circumstance. In pursuit of a living wage, musicians are required to work themselves into the ground.

In the foothills of autumn in 2020 my fiancée and I travelled to the West Country for a short holiday. Dividing our labour, she under- took the task of keeping us alive – like many music writers, I’ve never driven a car – while I was anointed DJ. Cueing up the latest album by the emerging South Coast rock group Creeper, I allowed my mind to drift gently in the direction of the book, this book, that I was due to begin writing in just seven days’ time. As the accents out- side our little red car began to change, the CD in the stereo ended with a sad and fragile song of which I’m now reminded:

Getting high has got us so low.

All my friends.

All my friends.

All my friends hurt.

Ian Winwood’s Bodies: Life & Death In Music is out this month via Faber.

Editor’s note: The disclaimer below refers to advertising posts and does not apply to this or any other editorial stories. LA Weekly editorial does not and will not sell content.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.