Rebecca Campbell’s current exhibition at L.A. Louver puts the history in art history. Infinite Density, Infinite Light presents about two dozen paintings and a sculptural installation made in the past three years that counterbalance masterful technique flexes in scenes of lush, radiant beauty and intrepid innocence that ponder the profound traumas inflicted by society and worse, by one’s own family.

Campbell has often mined her upbringing and elusive family narratives as her conceptual inspiration and actual subject matter. From the use of found photographs from her childhood and multiple generations of family both known and estranged as portraiture and motif, to a more story-based survey of her journey away from a controlling, religious, deeply conservative life, Campbell’s vision remains complex, paradoxical, and full of contradictory emotions from rage to loyalty, resentment and deep abiding love.

Rebecca Campbell, Beautiful Boy, 2019, oil on board, 18 x 24 in (Courtesy LA Louver)

What has always been so interesting about Campbell’s work is how she balances the rendering of deeply personal, specific events with a thoughtful, intentional conversation about artistic style, technique and abstraction. It’s almost as if while she’s wrestling with the legacy of her family, she’s wrestling with her art historical ancestors as well. In both cases, the trick is to simultaneously both embrace and explode the inheritance — to figure out how to take what is given, reject what is oppressive, and make it all into something new.

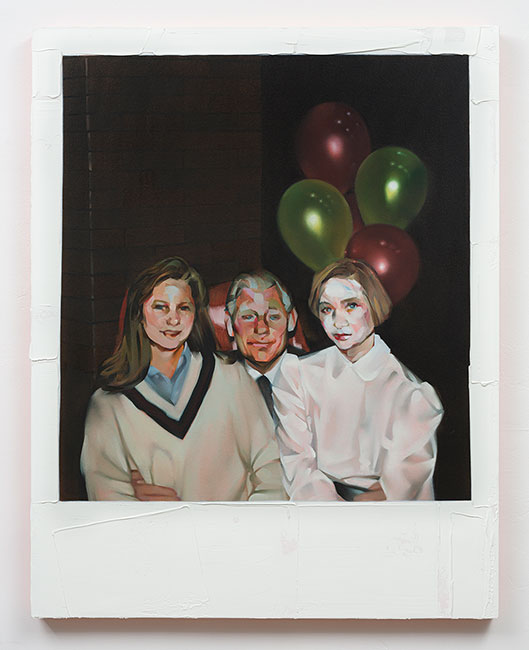

Rebecca Campbell, Bricks and Balloons, 2020, oil on canvas, 50.5 x 40 inches (Courtesy of LA Louver)

She accomplishes this in several ways. A direct link to the past is expressed in not just her sourcing from old photographs, but in her deliberate inclusions of clues and artifacts as to the images’ origins as family snapshots (flatness, focal planes, polaroid border). It’s never not clear that you are looking at transformed found photos, and this signifies that for Campbell, the past is still very present. Her unmistakable augmentation and manipulation of the imagery — through the agency of myriad expert painting techniques and art historical citations — succeeds in creating an emotionally rich postscript to the past that has everything to do with the present.

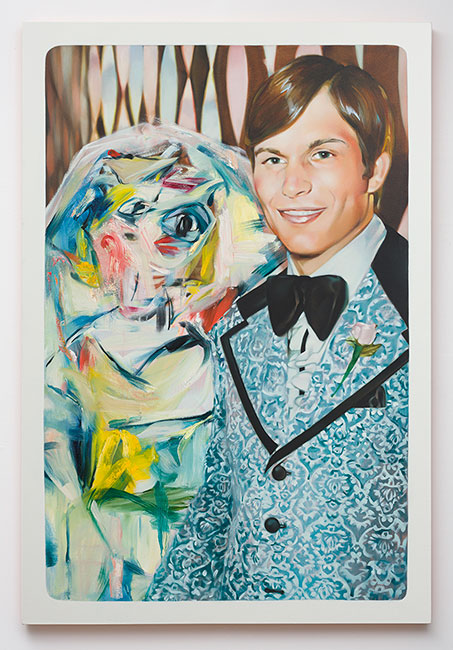

Rebecca Campbell, To Have and to Hold, 2019, oil on canvas, 75 x 51 inches (Courtesy of LA Louver)

The bride in To Have and To Hold all but disappears behind a veil not of lace but of violent post-Willem de Kooning abstraction, creating a double helix of meaning in which both the abuse behind the perfect couple veneer and the depairing misogyny of so much postwar American painting find their expression. In order to accomplish this twinset of resonant allegory, Campbell employs several distinct, and distinctly oppositional, visual idioms. For the woman’s auric chaos to work as something every woman recognizes instantly for what it is, the rest of the picture (aka the man and his amazing Baroque tuxedo) has to flirt with convention, obliviously. The balanced imbalance in psychological energy reflected in the intimate scene of optical disparity conflates personal and academic legacies.

Rebecca Campbell, Radiant White, 2020, oil on canvas, 88 x 109 inches (Courtesy of LA Louver)

In Radiant White, wide brushstrokes of white paint literally whitewashes the figures, in a unsettling trope of innocence that actually speaks to the whitewashing of history and the predominantly caucasian makeup of the group of schoolgirls — representing in turn an institutional education and institutionalized gender roles, just more of what Campbell is confronting and repairing in this work.

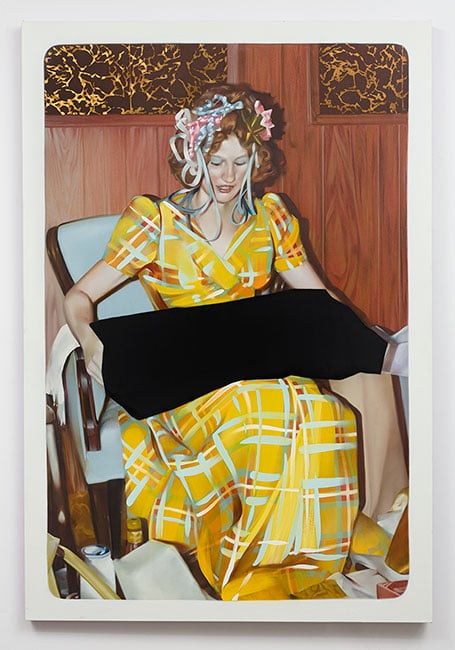

Rebecca Campbell, Vanta Envy, 2020, oil on canvas, 75 x 51 inches (Courtesy of LA Louver)

In Vanta Envy, a black obelisk that doubles as a gift box is an alien monolith intruding on a scene of ritualized frivolity and desire with a harsh geometrical abstract shape straight out of modern art. In Trevin the plaid is a symbol of both belonging to a legacy (it’s her traditional family plaid) and of breaking that tradition specifically in the punk movement and especially with bad boy boyfriends. It’s also the occasion for a delicate, complex, pattern-based palette-forward passage of abstract painting.

Rebecca Campbell, To the One I Love Best, 2021 (Courtesy of LA Louver)

To the One I Love Best is a multimedia installation incorporating family archives of documents, letters and personal ephemera from love notes between grandparents seeming to bespeak a romantic past, to her own collection of concert tickets and other souvenirs of early rebellion. Its diaphanous textiles are arranged on a low scaffolding that occupies the center of the room in a way that both screens and frames the portraits arrayed around it.

Rebecca Campbell, To the One I Love Best, 2021 (Courtesy of LA Louver)

It is the literal center of the story, which began in love and struggle and so far, has proceeded through the generations with the same — right down to the artist evaluating her own experience even as she is considering the precarious futures of her children. Light effects trace the arc of the sun, creating colored raking light which rises and sets across the work, so to speak, every day, while activating its veils and layers and printed and embroidered messages. It embodies how our memories are constructions, malleable and subject to revision and shifting emotions.

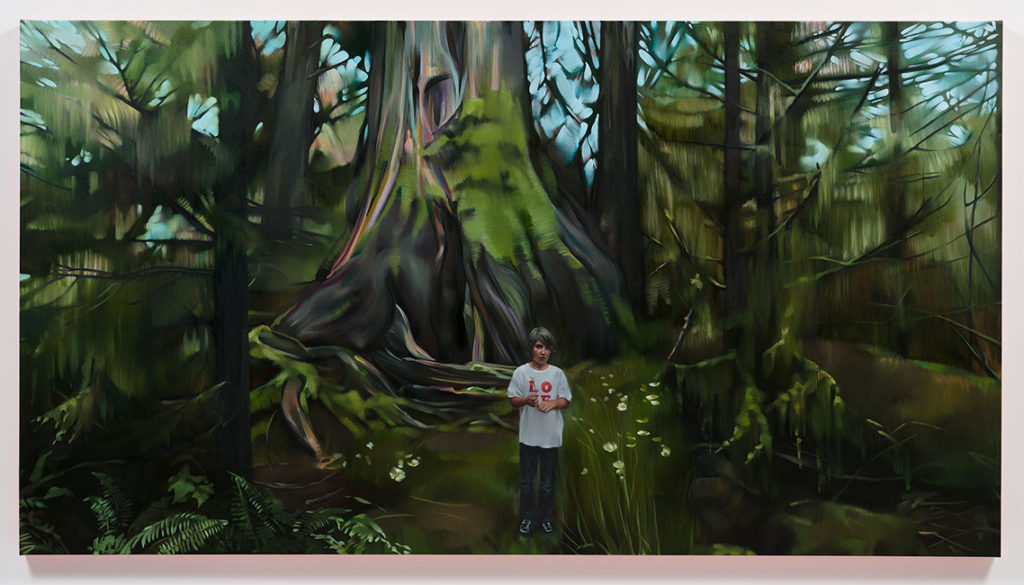

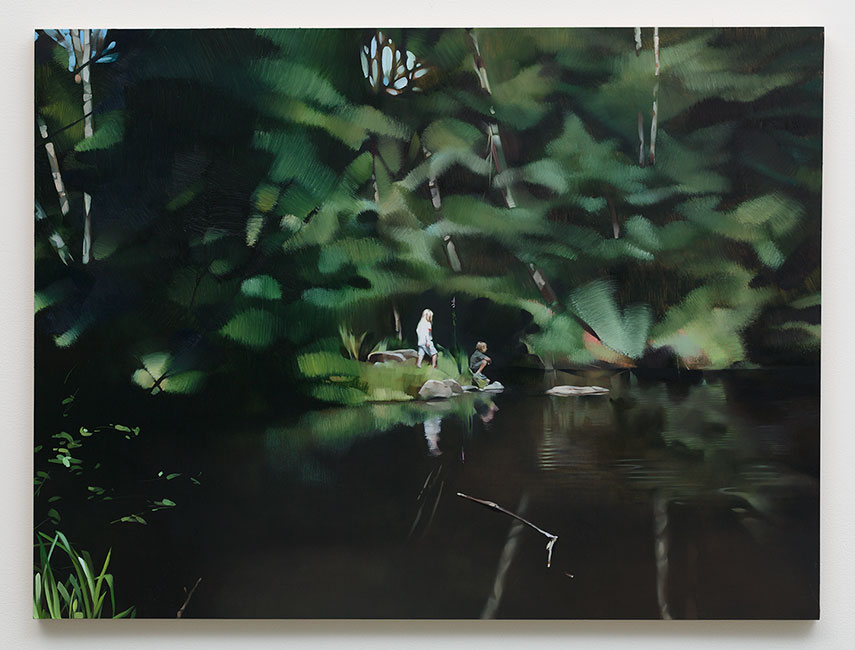

Rebecca Campbell, Nature Boy, 2021, oil on canvas, 60 x 110 in (Courtesy LA Louver)

The several paintings of lavish natural landscapes of forest, field, stream and shore are so fertile, peaceful, safe and aggressively picturesque in both image and style that one cannot help but think, ironically, of the dangerous polluted mess in which so much of the planet currently finds itself. The threats (political, ecological, pandemic) don’t need to be rendered in the picture because they’re already there in the viewer’s mind — but sometimes Campbell still puts symbols of them in there. The scenes are visually intruded upon by intentional glitches in their matrix in the form of physical paint — drips, swipes, dissolutions, disjunctures and seeds of color that point to their embodied existence as works of art as well as to the intrusions of adulthood on the consciousness of the subjects. The children in these landscapes are Campbell’s own, and this is both a continuation of the thread of family lineage toward the future, as well as the expressive portrayal of beings whose journey she watches closely as they grow increasingly involved in the big bad world.

Infinite Density, Infinite Light is on view at L.A. Louver, 45 N. Venice Blvd. in Venice through July 2; lalouver.com.

Rebecca Campbell, Reflection, 2021, oil on board, 36 x 48 in (Courtesy LA Louver)

Rebecca Campbell, installation view at LA Louver

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.