There are a handful of historical women of color whose names we all know due to their bravery and significance as activists. Harriet Tubman. Rosa Parks. Ida B. Wells. Angela Davis. These figures were not alone in their fervor and fights for equality, but their resistance to oppression was so bold they could not be ignored, even if it meant putting themselves in danger to right wrongs against their people and create change. It’s not too far a reach to say that San Fernando Valley native Patrisse Khan-Cullors deserves recognition alongside these iconic social justice figures, or that one day children will be reading about her in history books as they do those powerful women. They should be, anyway.

Cullors is the co-founder of Black Lives Matter, as well as Dignity and Power Now. BLM evolved from sentiment to hashtag and ultimately into a movement that — despite being viewed as controversial by some — generated an ongoing conversation about race, and specifically the treatment of people of color by law enforcement. DPN is an L.A.-based grassroots group created to take on corruption and mistreatment by L.A. County Sheriff’s Department and advocate for incarcerated people by building a black- and brown-led movement seeking alternatives to imprisonment. Rooted in community power with the goal of achieving “transformative justice and healing justice,” DPN led Cullors to focus her fight by forming other, more targeted groups for change as well, including JusticeLA — a coalition of organizations across L.A. County fighting against a proposed $3.5 billion jail construction in downtown — and Reform L.A. Jails, a committee to support a countywide ballot measure in March 2020 that would grant a civilian oversight commission subpoena power to investigate misconduct by the Sheriff’s Department. Moreover, the latter would work on a plan to reduce the jail population and redirect the cost savings into alternatives to imprisonment such as mental health programs.

“I’ve always been deeply impacted by incarceration and policing,” Cullors tells L.A. Weekly, as we sip beverages inside Hilltop Coffee + Kitchen, a hip cafe on Slauson Boulevard in South L.A. “In some ways, those were the first institutions that I had to deal with as a young person. Not schools, not church, but police and jails. And those two institutions created a lot of destruction and decimation in my community and in my family… and a lot of trauma. And so as soon as I got old enough to understand that I can change it, it was one of the first systems that I wanted to change. When we started Dignity and Power Now seven and a half years ago, we were actually at the forefront… I believe that the people closest to the pain should be the ones that are trying to change those systems. There weren’t a lot of formerly incarcerated people in Los Angeles County or their loved ones being asked to be a part of changing things and be a part of this campaign. So [we] really built that infrastructure.”

(Shane Lopes)

DPN’s model is for incarcerated people and, just as importantly, the people in their lives and community; it focuses not only on ideas but on actions. The Reform L.A. Jails ballot measure came to fruition two years ago, according to Cullors, emerging from JusticeLA’s battle against jail expansion. It led her to understand that real change occurs not only in the streets but through electoral politics.

“Certain community organizations can’t lobby,” she explains. “When you’re a [501]c3, you can’t lobby for legislation. As organizers, we need to have a multi-pronged strategy. I worked with lawyers and some policy folks to develop a framework around reforming the L.A. jail system and remov[ing] people with mental illness out of incarceration.”

Mental health and wellness are, in fact, huge components of Cullor’s platform. Just a few weeks ago, this was the central theme at an event the busy activist put together, “Reform L.A. Jails Summit + Day Party: Mental Health Matters,” at A Noise Within Theatre in Pasadena; it featured panels about how to decriminalize mental illness, how the mentally ill population has increased in jails, and how we can destigmatize mentally ill/homeless/returning citizens so that they might lead productive and happy lives.

Many of those in attendance and affected by discrimination in the criminal justice system shared their stories, galvanizing attendees to make their voices heard. With lively discussion focused on solutions, plus music, food and entertainment, it was an unexpectedly upbeat, cause-minded celebration of life and hope in spite of the dire circumstances that fuel her causes. Indeed, this positive spirit permeates everything Cullors does. Though she has devoted her life to tackling weighty issues concerning law, government and bureaucracy, her art background (she just graduated from USC with a Masters in Fine Arts) brings an expressive and soulful dynamic to everything she does.

“Patrisse has been on the front lines of fighting for justice for many years,” states Christman Bowers, her colleague at Reform L.A. Jails. “As someone who was called to action by #BlackLivesMatter, Patrisse has grown to understand that black policy matters too, and she has helped secure countless victories that have undoubtedly improved outcomes for L.A. County’s most vulnerable residents.”

At L.A. Pride 2019 (Courtesy Patrisse Cullors)

“As a consultant, I come across many leaders,” Bowers adds. “But Patrisse is in a different category. She teaches and inspires goodness, uses her power to protect the oppressed and she isn’t afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble. Those are attributes of a leader ready to endure the struggle of a lifetime.”

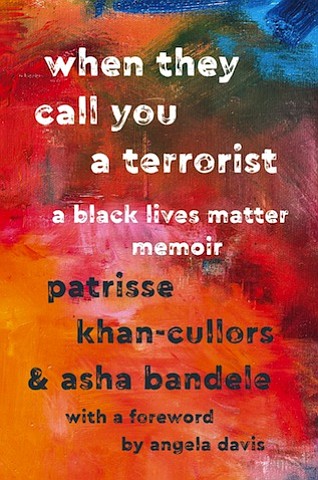

In her New York Times best-selling book, When They Call You A Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir, Cullors recalls a childhood filled with inequity and strife, especially in terms of opportunity, education and living conditions.

Cullors grew up in a community consistently targeted by police. She was raised by a single mother in Section 8 housing in Van Nuys along with her sister and two brothers, one of whom would later be diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, contributing to multiple trips to prison. (That brother, Monte, was found in jail on Thanksgiving morning after he’d been missing for two days. He is currently in the psych ward at Olive View hospital and Cullors has been tweeting about his situation under the hashtag #loveformonte.) Her biological father (who she learned about at 12 years old) was also caught up in the prison system due to crack possession and addiction. Cullors saw firsthand the crisis of poor communities, and specifically black communities. She saw how marginalized people are set up to fail and rarely, if ever, given the resources they need to succeed, leaving them few choices. When they turn to illegal activity, it only validates the system that’s in place and the cycle continues.

(St. Martin’s Press)

“It was really clear to me that my community was under attack,” Cullors says. “When I went to school in Sherman Oaks, only a few blocks over, I saw that that community wasn’t. There was a stark difference. I was in the performing arts magnet program and it was very white, middle-class, wealthy families — and I never saw police in that community.”

Despite the limitations of her surroundings, Cullors’ intelligence and drive led her to excel in school. She also experienced discrimination and police targeting, but she figured out why at a young age. “You know, we have this idea of a person who sells drugs; that they’re this terrible, horrible human being,” she explains. “And my argument is, ‘what happens when you’ve got an entire community of jobs and you’ve got an entire city with the ability to have employment or teach skill sets?’ Things are different. But people do what they can do in order to feed themselves and their family. Selling drugs or selling sex, [these are] pretty much the same issue — these are crimes of poverty, and what the city’s response and the county’s response should be is how do we employ people, not how do we jail people.”

Cullors first made an impact at 18 years of age as spokesperson for the Bus Riders Union (an organization that pushes for more funding within the public transit system), which she got involved with through a youth leadership program at the social justice magnet high school she attended in the Valley. While she was always socially active and focused on speaking out and utilizing channels such as organizing and protesting, her passion for artful expression fueled her work as well. She identifies as a queer performance artist, and she uses imagery and movement in uniquely powerful and provocative ways with the goal of sharing her experience.

Just this past summer, she presented a piece called Respite, Reprieve and Healing: An Evening of Cleansing at Highways Performance Space/Gallery’s 30th Anniversary, melding elements of performance, live music, sculpture and improvisation to represent the experience of black queer women and how government — especially the current administration — has devalued and disenfranchised them. At the same time, the piece celebrated the resilience of those deeply impacted by these harmful policies and sought to address trauma via a thought-provoking hair washing performance and symbolic bath, incorporating coconut milk, salt and honey as a form of release and meditation.

Respite, Reprieve and Healing: An Evening of Cleansing at Highways (Giovanni Solis)

Cullors also participated in this year’s L.A. Pride parade memorializing black trans women and black cisgender women who have been tragically murdered due to homophobia and intolerance. In solidarity with the activism and legacy of Stonewall, as well as Black Lives Matter, she rode alongside fellow activist Ashlee Marie Preston in a convertible covered with flowers and held a sign that read, “I will protect black trans women” as Beyoncé’s “Run the World (Girls)” played on repeat from the car stereo. She also passed out roses in remembrance of those murdered.

“Patrisse Cullors is one of the most visionary, brilliant, courageous and committed leaders of our time,” asserts Melina Abdullah, who co-founded the L.A. chapter of Black Lives Matter. “She picks up the mantle of black freedom struggle that began the moment that our people were stolen from Africa. She has built what is inarguably one of the most important movements of this era…Black Lives Matter. Her vision and labor have been a spark for black people globally to step into our sacred duty to demand and win freedom and justice.”

When L.A. Weekly profiled the leaders of Black Lives Matter back in 2015, Cullors was on bed rest due to pregnancy complications (she now has a preschool-aged daughter). While she was quoted extensively, she was not able to attend the photo shoot and hence did not appear on the cover (something we remedied this week). It was a big omission considering she is the best known face of the movement, having coined the now-global hashtag, and was the driving force in shaping its intersectionality (with inclusiveness of all gender identities) and its “tactics of disruption.”

Respite, Reprieve and Healing: An Evening of Cleansing at Highways (Giovanni Solis)

In the wake of the 2013 killing of Trayvon Martin by then-officer George Zimmerman, and his subsequent acquittal, Oakland-based activist Alicia Garza was lamenting the injustice in a post on Facebook. She included wordage that “black lives matter” which Cullors turned into a hashtag in the comments section. #BlackLivesMatter was a simple yet potent statement that resonated, a heartfelt reminder and to many, a call to action. As it spread, Garza, Cullors and BLM’s third co-founder Opal Tometi quickly understood they had the makings of a national coalition that would not only give black people a voice on the epidemic of police brutality which they had long suffered, but also provide a focused and unforgettable means of protest against violence and systemic racism in general.

Of course, it was polarizing. Law enforcement agencies were defensive, if not antagonistic, and many white people just didn’t get it. Many still don’t. Attempts to counter the hashtag with others (#BlueLivesMatter or #AllLivesMatter) weren’t about inclusiveness, they were about co-opting and undermining BLM’s influence. By contrast, the BLM movement has also opened the eyes of many, most significantly, of those lucky or privileged enough to have not have experienced discriminatory profiling, harassment or violence. #BLM (and later #MeToo) arguably led to what is one of the best facets of so-called woke culture: People not directly affected by societal mistreatment or injustice have been “awakened” to other human beings’ realities, and have attempted to put themselves in their shoes to function as outspoken allies.

Patrisse Cullors, Zuri Adele, Yara Shahidi, Diana Zuniga, Christman Bowers and Helen Jones-Phillips attend Reform L.A. Jails Summit + Day Party: Mental Health Matters (Jesse Grant/Getty Images for Patrisse Cullors)

Portrayals of BLM as something negative, extreme or non-unifying either miss the point entirely, or haven’t actually listened to Cullors’ ideas or intentions. As her book illustrates, it’s not about terrorism, it’s about truth. “Black Lives Matter was of course positioning us to challenge police violence, but this includes all marginalized people — immigrant detention centers, for example,” elaborates Cullors, who admits that while she hoped the phrase would go viral, she had no idea just how big it would get. “That comes out of the idea of imprisonment too. Right? Detention centers are prisons. So we have to address the ways in which anti-black racism has shaped all of our lives and our cultural understanding of who’s worthy.”

Recognizing that everyone is worthy of their own dignity is at the core of what first drove Cullors to become an activist, and for those fortunate enough to converse with this legend-in-the-making, her resolve for change is undeniably clear. There is strength but also warmth — in her smile, her words and in her essence. Her success is no accident, either. Hard work, education and an unwavering desire to acknowledge, empower and understand, have taken her far, but so has her ability to sense what resonates on social media and in media as a whole. Her most recent hashtag campaign, #CancelMcCarthyContract, scored a victory when the L.A. County Board of Supervisors voted to do just that, scrapping a $1.7-billion contract with McCarthy Builders to replace the Men’s Central Jail downtown with a new facility that would again, only prioritize “caging, not care.”

(Read this story in the L.A. Weekly print edition out now).

Soon she’ll be passing her skill set on to others too. Prescott College in Arizona recently announced a new Social and Environmental Arts Practice MFA program helmed by Cullors. It’ll be the nation’s first of its kind, with curriculum covering the intersection of art, social justice and community organizing. Students will have the option to complete a residency at The Crenshaw Dairy Mart, Cullors’ L.A. arts and events studio.

“I’ve been truly impressed by her ability to be a catalyst for change,” notes Abdullah of Cullors’ all-encompassing approach. “Often activists do not understand that we must embrace an outside/inside political strategy to win. Not so for Patrisse. She knows how to push our broken systems on the outside with protest and, when necessary, work with elected officials and stakeholders on the inside with wisdom.”

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.