The world completely changed in 2020, as people were afraid to be anywhere near one another, questioned every minor pain or abnormality they felt, and walked around in public with surgical masks as if they were full-time medical professionals.

Through those changes, certain names became commonplace, such as Dr. Anthony Fauci on a federal level, Dr. Mark Ghaly on a state level, and here in Los Angeles County, the voice that kept us updated on the dire situation of the world was that of Public Health Director, Dr. Barbara Ferrer.

L.A. County was literally on lockdown. People began working from home, many laid off due to business clousres, and as more Angelenos were home-bound, part of their daily routine consisted of watching Ferrer’s daily COVID-19 updates, as at the time, we had very little idea of what type of virus we were dealing with.

Ferrer was just like us, delivering most of her addresses remotely as to stay away from others and prevent the virus’ spread – and like us, she had to adjust to speaking through video streams as the world became reliant on streaming programs such as Zoom, FaceTime and Google Hangouts as primary forms of communication.

“Very often I was talking about people who were dying, or people who were very sick, people who were scared because they had a lot of exposure at their job. There were a lot of unknowns and it’s hard to manage any crisis when everything is brand new that people are experiencing,” Ferrer said. “Nobody had lived with this virus before and we didn’t know much about it. The information was changing constantly and you’re trying to make sure people have access to really good information, but that information changes and sometimes it’s contradictory. We spent the first three months telling people they didn’t need to wear masks and now the one message we say every single time when we’re talking to people is, ‘You got to wear a mask.’”

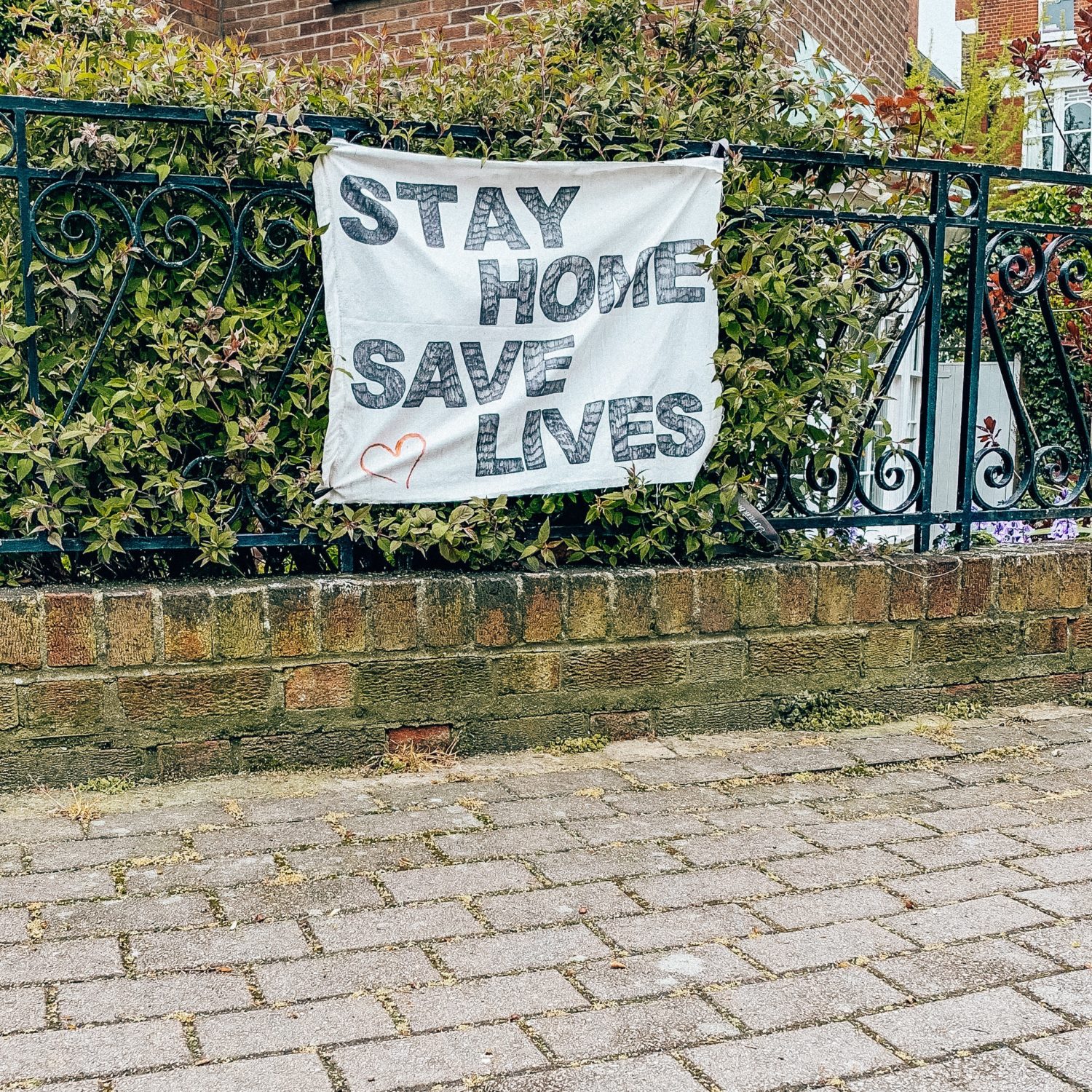

(Stephanie Martin/Unsplash)

Ferrer grew up in Puerto Rico, but was well-traveled during her schooling, attending U.C. Santa Cruz in California before heading east to Boston University to get her Master’s degree in public health, a Master’s in education at the University of Massachusetts, and eventually her doctorate at Brandeis University.

She has spent most of her working life in public health and community organizations, serving as chief strategy officer for the Kellogg Foundation in Michigan and before that was the Executive Director of the Boston Public Health Commission, all before making her way back west to help lead the team of Los Angeles County Public Health.

When Dr. Ferrer was appointed the director of Public Health in 2017, she never imagined she would have to navigate through a global pandemic of this magnitude. This isn’t the first time she’s had to deal with a crisis, however. In Boston, she worked directly with handling the Boston Marathon bombing, the H1N1 pandemic and even the Ebola virus outbreak.

“We’re all trained for responding to a pandemic, obviously, as public health practitioners… we’re also all trained in emergency response,” said Ferrer. “We are trained and trained well, but I don’t think anybody who works in public health envisioned a pandemic quite as severe as this pandemic and as extensive and long-lasting.”

In hindsight, Ferrer said we should have seen the spread in China and predicted that it could happen here, but without anyone from the U.S. to properly document what was happening in China, there was a feeling that the virus was spreading because their “system is so different.”

“I don’t know if we could have known, but we might have had an inkling that things could get really rough,” Ferrer said.

Restrictions and regulations in Los Angeles were dictated by the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Working together with the state public health officials, L.A. County and all California counties had the difficult task of deciding how much person-to-person contact it wanted to risk in accordance with the infection rates in their areas. These decisions were not always taken in stride, as businesses had to shut down and everyday life was affected by the decisions. This led public health officials, such as Nichole Quick in neighboring Orange County, to resign, as opponents of the restrictions went as far as sending death threats.

These threats were something that Ferrer had to deal with during the pandemic as well, with people going as far as protesting outside her home.

“Some of the public health folks that resigned, it was due to not having enough support… from people who were elected, from people who are supervising you and you know, from a team,” Ferrer said. “We have far more people, that’s just very quiet, that thank us, who call us, send flowers. We got a lot of love from thousands of people from across the county who we don’t know but have also been with us through this year… as we’ve all tried to make our way through this difficult year.”

Ferrer said she understood people’s frustrations during the pandemic, but she was not deterred and kept pushing forward with support from the team around her.

(Adam Nieścioruk/Unsplash)

Another phenomenon that was a byproduct of the pandemic, was a rise in the spread of unfounded conspiracy theories ranging from vaccines being embedded with microchips, to planned enslavement by the government of the American people. In these plots, people in power and public officials had been leading characters in the conspiracies and Dr. Ferrer was no exception.

“I’m not on any social media accounts, at all… but people have shared with me, you know, people are saying, ‘You’re a Cuban terrorist from Cuba. This is why you’re here,’” Ferrer said. “The conspiracy theories are fanatical and fantastical and they’re really not grounded in any reality. I never thought that would be a part of my life, ever.”

L.A. County has seen ups and downs throughout the pandemic as the virus’ spread gradually increased through the early months of 2020, then seemingly got better before hitting a peak in January of 2021, with high COVID-19 case rates that have not been seen since.

Now we are in the midst of what California is calling a “grand reopening.” There are still minor pandemic provisions in place and close monitoring of person-to-person spread, but with vaccination rates increasing and the number of positive COVID-19 cases at steady lows, both the state and L.A. County are starting to see signs of normalcy after a year and a half of devastation and seclusion.

Businesses may now open without capacity restrictions, sporting events are being played in front of live crowds and the masks that made us look like a nation of old-timey bank robbers are now a thing of the past. We are able to see loved ones, work among colleagues and walk the street with less fear of the unknown.

As normalcy gradually returns, Ferrer said she cannot wait to spend more time with family and see her grandchildren, as it was hard for her to be away from her loved ones for the better part of a year.

“That’s been the hardest part of this, the isolation, for those of us who love to be connected to people who we care about,” Ferrer said. “I haven’t been able to travel and that meant not seeing my grandchildren for many, many months. We just saw each other for the first time since all the adults are vaccinated. I empathize with all the families that have been living through this.”

As the state of California cautiously and optimistically reopens businesses and day-to-day activities, there is still risk lurking. With COVID-19 infections not fully gone, the possibility of spread between unvaccinated people and other parts of the world still suffering from the virus still exists.

If all goes according to plan, we may not see Ferrer on our TV screens as often, or have to worry about any surges in COVID-19 infections, but with the madness and sadness that defined 2019-2021, Ferrer was able to oversee it all and find a silver lining.

“I think when we look back, the thing that’s going to resonate and stick with me the longest is how many people helped out other people,” Ferrer said. “We all know that the majority of people here in L.A. County did everything they could to take care of not just themselves and their family, but everyone. The acts of kindness… that was really what was most powerful, was our ability in the midst of this horrifying and scary and frightening time, to watch how many people came together to take care of each other.”

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.