There are many things you could call Henry Taylor — streetwise truth-teller, portrait realist, found objects sculptor, pocket sketcher, Caliblackifornian — but one thing he is not is patient. There are likely many good reasons for that, and we are all beneficiaries of his bottled up brush strokes.

One reason could be that his start as an artist — when he was “discovered” by the art world illuminati — came a little later than most. Born in Ventura in 1958, he went on to work as a psychiatric technician in Oxnard for 10 years before attending the California Institute of the Arts, getting his BFA in 1985. Some of his first works were of psychiatric patients, like “Split Person” and “Screaming Head.”

Henry Taylor at Blum & Poe Los Angeles in 2016, installation view

Another reason could be that he has such a proliferation of ideas and observations that he wants to get out. That may also explain why he uses a range of nontraditional materials — suitcases, cigarette packs, wood boxes — anything and everything is eligible to become part of the proverbial canvas. He used those unconventional techniques to great effect, when some would say he made his mark, during a 2012 residency and solo exhibition at MoMA PS1 in New York.

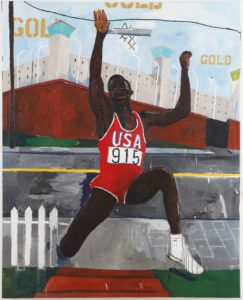

Henry Taylor, The Long Jump by Carl Lewis, 2010, Acrylic on canvas, 87 1/2 x 77 inches (Courtesy of the artist and Untitled, NY)

This idea-cramming aspect is wondrously illustrated in a piece called “The Long Jump by Carl Lewis,” which shows many dimensions of black maleness in America at once. We see the track superstar in mid-leap, but behind him there is a prison and in front of him a white picket fence. It maps a navigation for any number of black men trying to make their way through, and hurdle over, obstacles to land somewhere good. It’s a visual manifestation of the blues aesthetic.

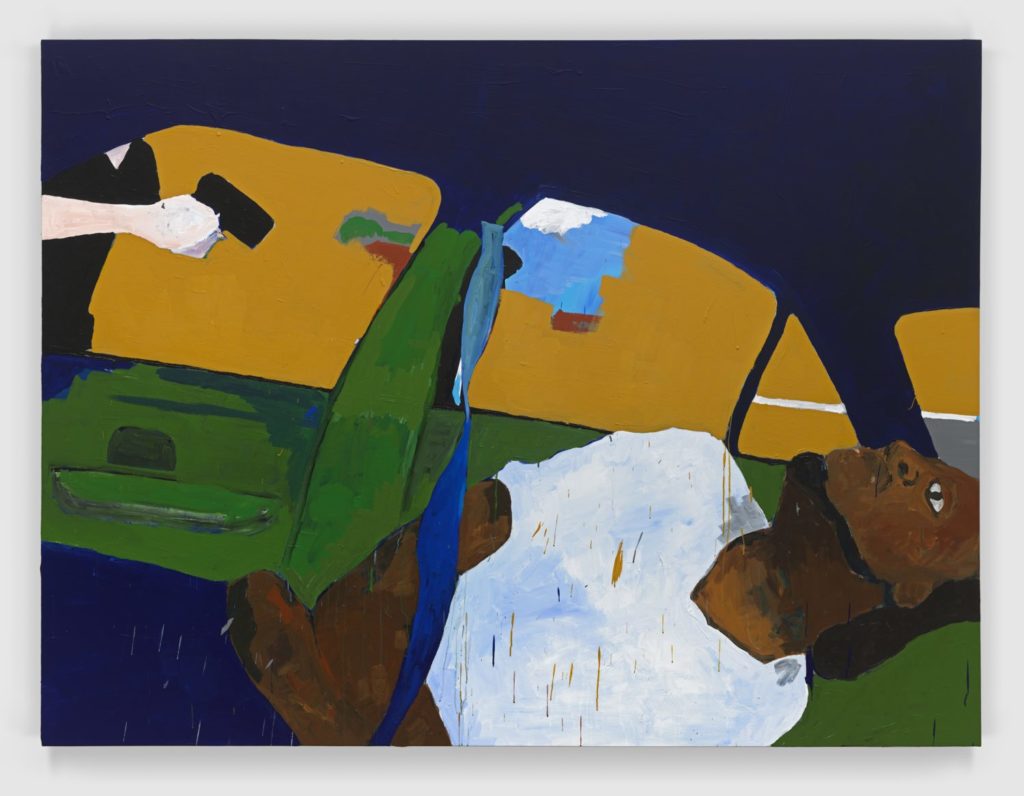

And there is perhaps a certain urgency to get out the truth about his subjects. “I pull my people off the damn street!” he exclaimed in a recent interview. “I’m on Skid Row, and I’m looking at people all the time.” And sometimes it’s reading the headlines, as reflected in the work “The Times Thay Ain’t A Changing, Fast Enough!” made in 2017 and shown that year at the Whitney Biennial in New York. It portrayed the dying body of Philando Castile, another black victim of race-based police violence. In it, the furiousness and truthiness get another play, like a favorite blues album on vinyl.

“It has to hit me,” Taylor said of the work. “I’m not searching for every death, but sometimes I get mad. And you see that, I was mad.”

blumandpoe.com/artists/henry_taylor.

Henry Taylor (Paul Forney)

Henry Taylor, THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH!, 2017, Acrylic on canvas 72 x 96 inches (Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo)

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.