Visual and performance artist Autumn Breon trained up and fully embarked on a career in aeronautics engineering before a series of inspirational events called her to pursue her creative side full-time. As an artist, Breon is concerned with creating images and experiences of beauty in the world — but always with the goals of justice, political and economic equity, and community care in mind. She recently debuted a new partly crowd-sourced performance piece, Protective Style, as part of The Performance Project at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles. Accompanied by perennial collaborators the Black Fist Brass Band and dancers, Breon enacted a pageant of received wisdom from ancestors on the planet Esoterica centering around the embedding of personal and societal self-care tools in the accouterments of Black hair salons.

Breon gets asked about the rocket science thing a lot, which is understandable. But L.A. Weekly also spoke to the artist about the process and meaning of Protective Style; her use of NFTs and blockchain smart contracts to enact pay equity for Black women; her ongoing residency at Los Angeles community creative center and “abolitionist pod,” Crenshaw Dairy Mart; and her imminent plans to travel the new performance piece as a voting rights activation.

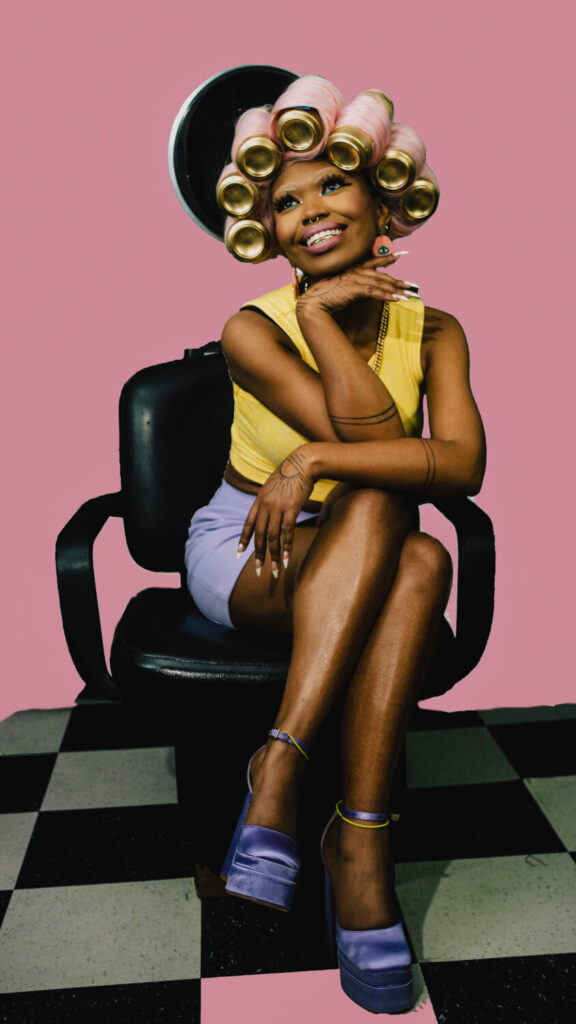

Autumn Breon: Protective Style at the Performance Project (Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, Photo: Giovanni Solis)

L.A. WEEKLY: Tell us about the relationship between your career in astrobiology and your work as a performance artist. And related to that, how do performance art and the digital space intersect for you?

AUTUMN BREON: I think that a lot of creativity is required for science, and I think that a lot of what I learned in practice as an engineer, I use as an artist now because I’m still using the scientific method. I’m hypothesizing, I’m experimenting. I modify how I experiment based on how the first try may have gone, and then I keep on tinkering until I get the solution. I’m trying to understand. I think these are real symbiotic relationships for me; I don’t see that much of a difference.

LAW: It sounds like you’re always asking, how do I literally get from here to there? In some cases that’s from Earth to outer space, and in some cases that’s from a place of racism, misogyny, and predatory capitalism to one of justice and fairness.

AB: Absolutely. And I also think that’s how abolition informs my work, because I’m imagining new worlds — the world that I imagine all of my art comes from. It’s called Esoterica. And I imagine that ancestors don’t die, but that they just go on to Esoterica when they’re tired of Earth’s bullshit. So I like to bring small rituals and ceremonies from Esoterica to Planet Earth. It’s a collective act of imagining that I’m inviting the audience into with me. It may not be me researching how microorganisms survive high in the atmosphere, but I’ll find something in history, get to understand it, and then invite audiences to learn what I learned — and then they respond to some kind of inquiry from me. So for this performance (Protective Style at Hauser & Wirth), I was asking people to respond to the question: Why do you go to the hair salon — other than getting your hair done? And I use technology, the internet and all these web spaces to invite more people into the call-and-response.

LAW: Which is something you do often. There’s a version of that engagement structure in all or most of the performances. That’s the research phase.

AB: Exactly. Exactly.

Autumn Breon: Protective Style at the Performance Project (Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, Photo: Giovanni Solis)

LAW: And the way that science builds on — they wouldn’t use the word ancestors in that context — but it is built on what people before you have learned and left behind for you to use in your research. There’s an expectation of generational forward movement. So what was the thing that made you decide to walk out of the lab and into the studio? Was there a time when it was both? What changed?

AB: Yeah. It was really when I was living and working in South Africa, that was a very significant milestone in me deciding to pursue my creative practice full-time. I spent a lot of time at biennials and art fairs and other artists’ studios getting to know curators and really understanding the arts ecosystem. When I was on the continent, I felt so emotionally fed in a way that I hadn’t before, and I started to literally just list my priorities for feeling fully realized. And one of them was to be around beautiful things and to create beautiful things. I said, I have to pursue that. I need to figure out what that means for me — to understand how I can use these skills toward interests where I see something that brings me joy, things that I enjoy doing and that I’m also good at. How can I do both? And that manifested through art. But I realized that I was always bringing creativity to what I did.

When I worked at Northrop, I was working on the James Webb Space Telescope, which we’re just now getting images from. And I consider that a creative feat because I was part of finding these images of the universe — that felt very creative for me. It just happened to be a different language.

Autumn Breon: Protective Style at the Performance Project (Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, Photo: Giovanni Solis)

LAW: And that speaks to why somebody whose practice is an embodied presence might not feel so separate from the discourse around something like, say, your work in the NFT ecosystem. But it seems like you’re already operating at a fulcrum where those things wouldn’t be as strange to hold in the same space.

AB: Possibly. I think I love what is strange. And I love to lean into the strange. So I was not an expert on blockchain, on NFTs; I didn’t understand that. But what really piqued my interest was that blockchain was a technology with a permanent ledger. That kind of transparency felt like a tool that I could use for the performance piece Don’t Use Me. The good folks at Voice.com answered all of my questions. They’ve been so great in how they work with artists. I was basically just telling them, I want a way where I can write women in as co-creators and where they can always be paid in perpetuity so that this is an ongoing action against pay inequity. And when they explained to me how the technology worked, I was able to leverage that.

LAW: We really saw, during the pandemic discourse on this, that the people pushing back against the NFT thing were, largely, the people who never really had this problem of not getting paid, not systemically. And then it was the communities that were banging on the door that saw its promise.

AB: Yeah. Yeah. That’s usually how it works though. Like it’s folks that have not experienced real equity, folks that have actually struggled — we’re the ones that have our antenna up to identify whether something is a solution that can either make an act more efficient, or that can make more basic needs be met. I feel like we identify those and probably experiment with them more quickly because we’ve experienced the need.

Autumn Breon: Protective Style at the Performance Project (Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, Photo: Giovanni Solis)

LAW: And as an artist, you are specifically looking for ways to ameliorate that situation because it’s necessary. So that manifested in the digital space in that work. But back to the performance art in personal space, I would love to talk more about the crowdsourcing parts of what you do — why and how that works and at what point in the idea does it fold into what becomes the final piece?

AB: I always know what my central question is going to be, and I pose that question to as many folks as I can. Well before that I share what I’ve learned with as many folks as I can, which is very intuitive for me because I have an intellectual curiosity where I love learning new things; but what I love just as much is sharing it with others. So when I learned about Bernice Robinson teaching adults how to read and write so that they could pass literacy tests (to vote), and the fact that she was a beautician and after her curriculum was so successful, many other beauticians in the South started doing the same thing — it blew me away. I thought that was incredible. I already knew that hair salons are charged-up places — because I know how I feel when I go to the salon. My studio has a working hair salon in it, so I get to witness that every day.

I wanted folks to find out about Robinson’s work, but I also wanted to find out: What are the other magical things that happen in hair salons — learning how to read and write, mobilizing, organizing, feeling like a new person? What else are people getting out of these charged spaces? So I posed that question by interviewing people at hair salons. I was posting on social media to collect these responses. I always use as many means as I can to collect these responses from folks. I’ve also had posters that I put up in different parts of L.A., with the phone number and the QR code. I had a booth that was shaped like a giant hair grease jar that was at Hauser & Wirth for a week. I collect all the responses and then I always wear those responses in my hair somehow, and the call-and-response continues when folks are invited to read another person’s words out loud during the performance itself. And, you know, the performance isn’t the only part of the work — that happens to be how it culminates. But I consider the art also being in the call-and-response with the folks that I collect responses from.

Autumn Breon: Protective Style at the Performance Project (Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, Photo: Giovanni Solis)

LAW: I think that you’ve really hit on a formula that also makes the general idiom of performance art more accessible, because it’s not that sort of solipsistic externalization of the individual psyche that we often receive. Having other people’s voices involved is centrally part of that. Do you feel like you’ve been able to see the fruits of this labor?

AB: Oh I do. I do see the fruits of my labor, and I’m also excited for what I’ll get to see next. I love being able to see and experience that kind of gratification. That’s something that I don’t take lightly. I love it after a performance, when folks understand it. And I felt really emotional after the performance (at HWLA) when someone was speaking to me after and they said, Hey, I felt really seen. And when I heard other people’s words being read aloud, it felt like something I would have said to answer that question. Yeah. I did what I needed to do and that makes me feel like I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing. I’m in the right place.

LAW: I want to get your reaction to the term Afrofuturism, which is so beautiful and yet has become so ubiquitous at this point. The reason I bring that up is because there’s like a space travel element to the visitors from Planet Esoterica, so I’m thinking a little bit about science fiction…not to mention your actual professional background in space engineering.

AB: I’m definitely influenced by many elements of Afrofuturism, Afrosurrealism, and Surrealism. But also just the huge amount of science fiction that influenced how I saw the world as a young person. That influences a lot of my choices.

LAW: Like to go to Rocket Science school.

AB: Yeah, right! I first became interested in astronautics and physics when I read A Wrinkle in Time when I was a kid. And the objects that I make, the performances that I make — I think of them as wormholes to liberation. So I don’t think of liberation as something that I won’t see in my lifetime or something that’s far away. You make it closer and more intimate, as if you’re just kind of compressing the distance that you have to travel to make that a reality. And I think that there are so many living paradoxes that Black women contain. And for us to still exist, to still thrive in a place that has created so many elements for us not to. I just think if anybody can time travel or has been time traveling, we’ve probably been doing it already.

Autumn Breon: Protective Style at the Performance Project (Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, Photo: Giovanni Solis)

LAW: And then from that point of view, a residency at an incredible place like Crenshaw Dairy Mart would make so much sense in your practice because of how it intersects with the social goals of that place.

AB: Absolutely. Absolutely. The Crenshaw Dairy Mart has played such an incredible role in my practice — especially with this specific body of work, with Protective Style, which I was able to work on while in my fellowship. That type of supportive community has been really important for my art making, and I think it’s especially important for this abolitionist aesthetic that’s growing — we can’t be making art in isolation. I love that the Dairy Mart has created the infrastructure for community — artists have always been doing that, especially in L.A., like the Black Arts movement, the Brockman Gallery’s Alonzo and Dale Davis. There have always been these cohorts and ecosystems of artists that create together. It’s beautiful to see that legacy continue through the Dairy Mart. And for me to be a part of it, I feel very blessed, very grateful.

LAW: How long does the fellowship last? What are you working on there now?

AB: Our culminating exhibitions are this fall; we’ve been having our weekly sessions since February of this year and that’s where we get to do studio visits, visit institutions, and have lecturers that come in. We get these great group discussions about some of the close readings that we’ve been doing. For Protective Style, Vote.org has been a really incredible partner. I’m so grateful for their support at the performance. There are QR codes that take you to Vote.org/Breon and in 30 seconds you find out if you’re registered to vote. And if not, you have the steps to follow so that you can get registered. My goal is to continue the legacy of Bernice Robinson and also the legacy of my grandparents. They really influenced this as well. They migrated to Watts from Birmingham in 1951. And when they came here, I remember this for my entire childhood, voting was always so essential. It wasn’t “nice to have,” it was something that was a must-have.

Everybody in my family — my aunts, my uncles, my cousins — for every election, at the dinner table at my grandparent’s house, we would use our voter guides and a pencil and we would just talk through everything that was on the ballot and mark how we were going to vote. We all knew where our polling places were in the neighborhood, and they would make sure, even if it wasn’t our family, but in the whole neighborhood, that if you needed a ride to go vote, my grandfather would pack people up and drive them over. They would volunteer at poll places. And as I became older, I understood what a big deal voting was for them because it was a lot more difficult to vote in Alabama before they came here and couldn’t. I was a tiny tot, but I would still get a little pencil, and I got to mark everything up. Sometimes we would have candidates come to the house for dinner. It was a safe space of care to talk about what we were voting for in layman’s terms, in plain English.

LAW: And that all fits together so marvelously — compressing the distance between here and a better future, by creating a safe space to discuss politics and make plans for collective and individual action, which definitely mirrors what goes on in the hair salons.

AB: Absolutely. That’s essential for every piece. I want to continue that with Protective Style — take it on the road and go to places where voter suppression is very real, and make sure that folks are as prepared as they need to be to vote. The first step is continuing to use this QR code and link and making sure that folks have as few barriers to voting as possible.

For information on projects and upcoming performances (and to check your voter registration status) visit autumnbreon.com.

Autumn Breon: Protective Style at the Performance Project (Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, Photo: Giovanni Solis)

Editor’s note: The disclaimer below refers to advertising posts and does not apply to this or any other editorial stories.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.