On March 20, California’s lockdown went into effect to combat the spread of COVID-19. Since then, artists and institutions alike have been swiftly adapting to new ways of making and sharing art while studios, schools, galleries and museums are closed.

Digital platforms like Instagram were already woven into the fabric of the art world, but in the absence of physical spaces they have turned into lifelines for community and communication. Many artists have begun to offer livestreamed art classes and prompts, including Bay Area illustrator Wendy MacNaughton, who started leading her 30-minute drawing classes for kids almost as soon as quarantine began. “This is uncharted territory, and we’re all stepping up in new and exciting ways,” MacNaughton said.

MacNaughton, who trained as a social worker, aims to provide “fun, silly, and interactive” sessions to help stressed-out parents whose children are now at home. Her joyful, high-energy presence on screen is balanced by her ability to create an emotional grounding that helps children process their feelings.

“Drawing is a creative activity, but it’s also focusing and calming…it’s very meditative,” McNaughton said. In the first week, her class drew an audience of around 2,200 live viewers, with roughly 15,000 views over 24 hours. She hopes to use the platform to build a sense of shared community, noting that, “the classroom just got a lot smaller, but at the same time it got huge.”

Other artists are fostering community and communal coping by sharing creative prompts. Dane Nakama, a third-year CalArts student, has been posting a multidisciplinary prompt on Instagram daily since quarantine began. With classes moved online, it was important to him to stay connected to other artists. “Regardless of the specific responses, you feel like you’re with others — that’s what’s exciting,” he said. Nakama keeps the prompts open-ended in order to create opportunities for interaction across mediums. “I’ve always understood the real art to be the interaction,” he said, “whether it be between the artists and the medium or between the viewers and the artwork.”

That interaction is vital for artists to continue their practice in a distanced world, not only to engage with community, but also to have opportunities to display and sell work. Art Share L.A., a stalwart organization for artist resources, has created a virtual gallery on Instagram while hosting daily home performances via Zoom.

Benjamin Cook, an artist and adjunct professor at the Art Academy of Cincinnati, started the Social Distance Gallery after his students’ BFA show was canceled along with those of many other schools. The Instagram account showcases BFA and MFA students’ thesis projects, creating “opportunities for visibility [and] network building.” Cook said that he wanted to use the digital project “to not only help students, but to recontextualize how people look at the experience of viewing art.” This moment, he said, will force a reassessment of digital images as “an important part of how art is now consumed, rather than…a lesser version of a physical gallery show.”

Cook noted that, like physical venues, digital platforms are subject to inherent bias — in this case, through algorithms that can reinforce societal privilege. “If visibility and success are partially linked, Instagram takes the flawed system of inequality that exists in a physical world and heightens it,” he said. The allure of immediate, global connection comes with the danger of reinforcing systemic barriers. Artist and educator Micol Hebron also pointed out the issues of equitable access that arise, from access and understanding of technology to physical ability.

Artists Samuel Borkson and Arturo Sandoval III, the co-collaborators of FriendsWithYou, see this as a transformative period for artists to question societal structures. “There’s no choice but to take in this moment and have it be a part of your art,” Borkson said. As they and their studio assistants work remotely on ongoing works, they are brainstorming projects that will support and entertain people during the crisis, including coloring books and online tools for people to build their own FriendsWithYou-inspired art.

“The focus of our art has been to bring people together, and now more than ever I feel that’s essential,” Sandoval said. “This moment is bringing to light that we have to act as an organism that is connected; that situations like this we cannot face alone.”

Artists are indeed part of an ecosystem, which includes museums struggling to stay connected to audiences who can no longer visit. Many shuttered institutions are providing alternatives by shifting to virtual exhibitions. The Annenberg Space for Photography released an online audio tour of their latest exhibit, Vanity Fair: Hollywood Calling. That and their Photo Ark guides garnered around 5,000 listens in their first week of release — a remarkable demand, given that they average around 2,000 visitors weekly. As Director Katie Hollander explained it, art is “providing a human touch and connection — something that we need more than ever right now.”

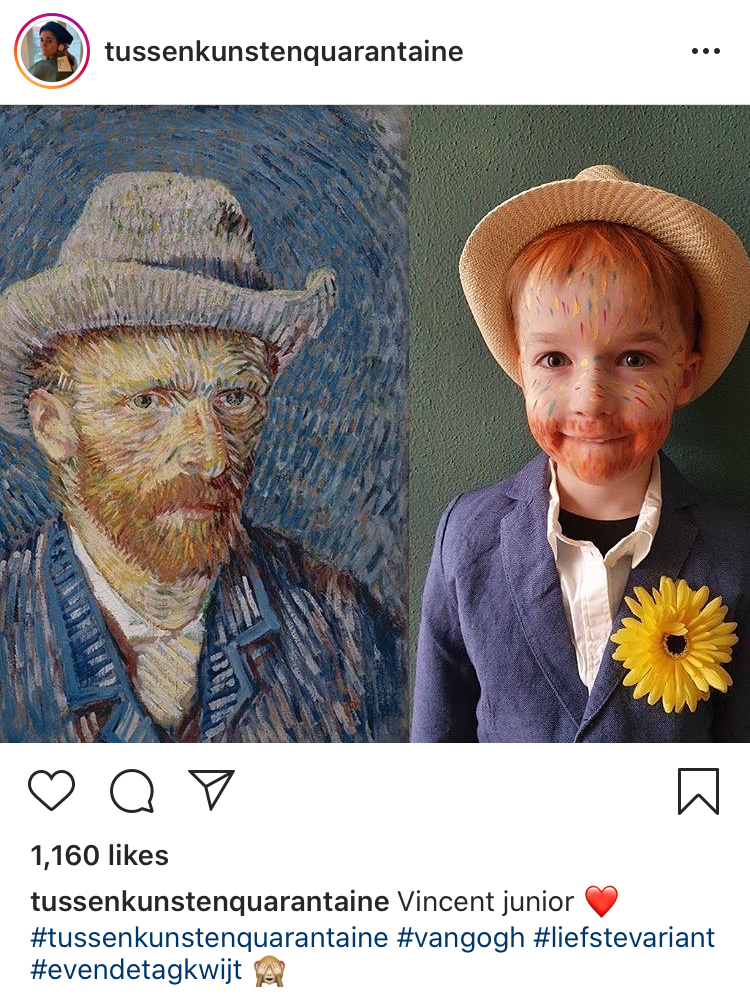

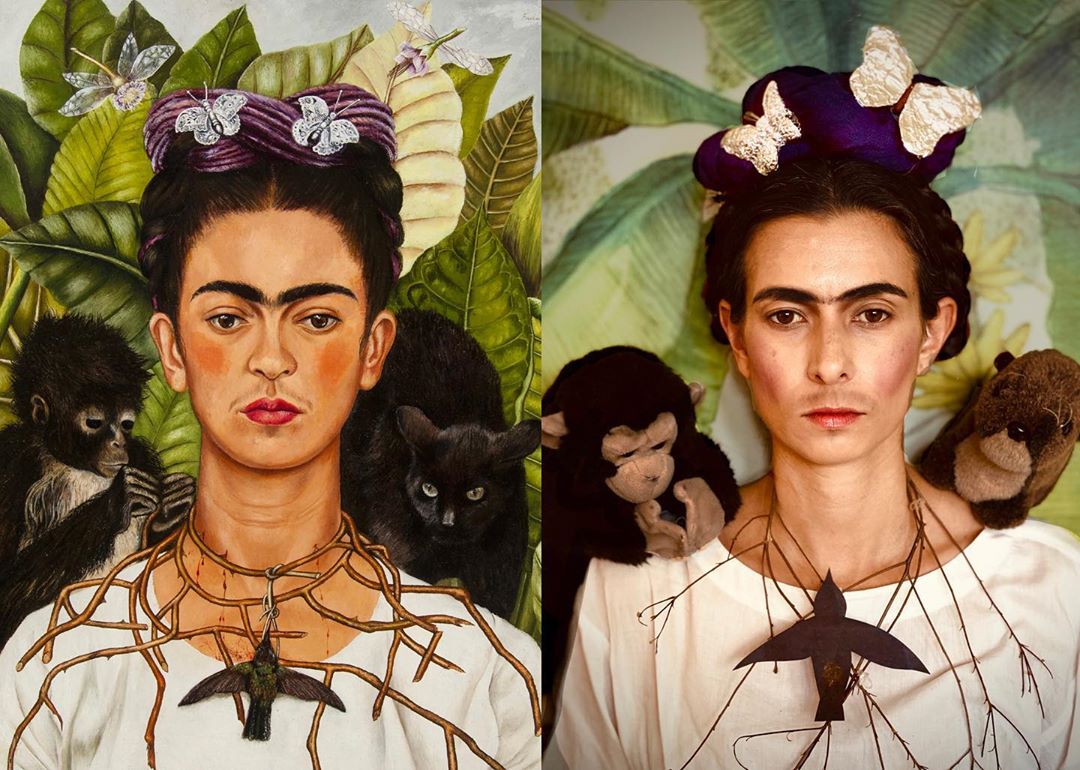

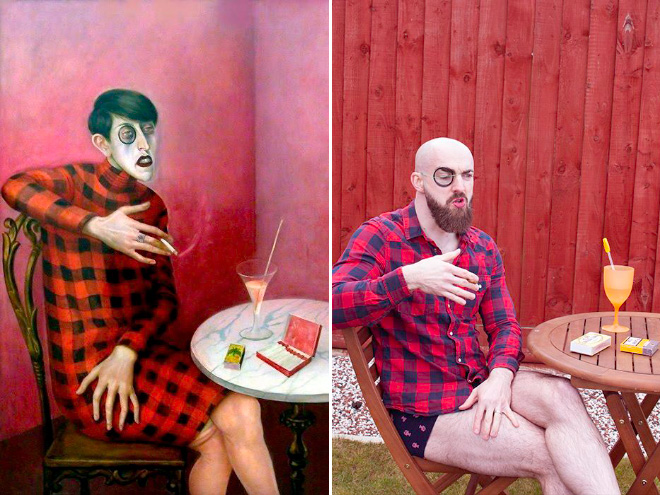

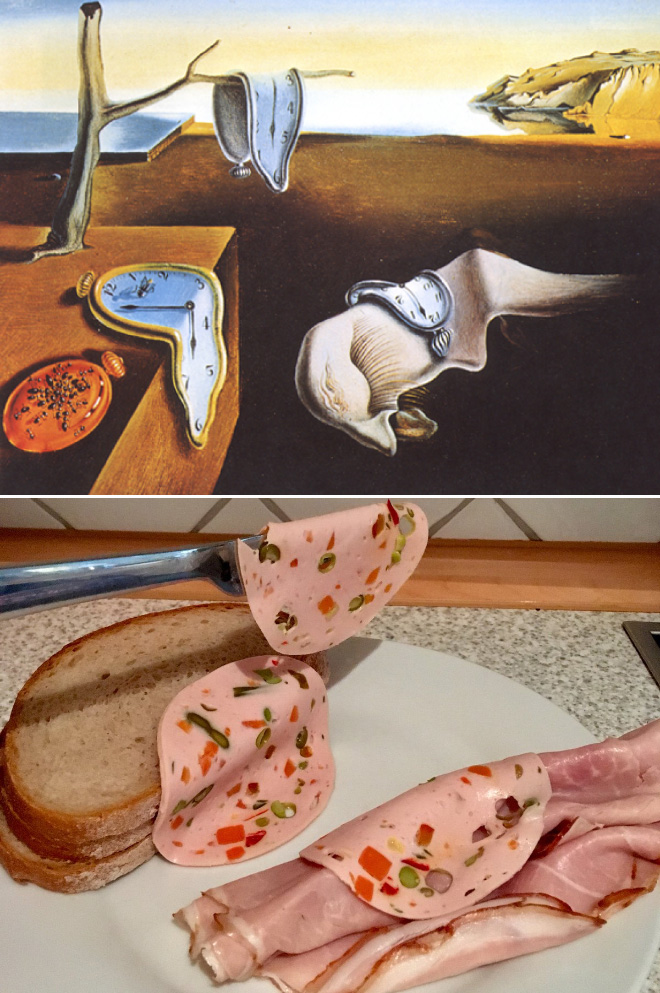

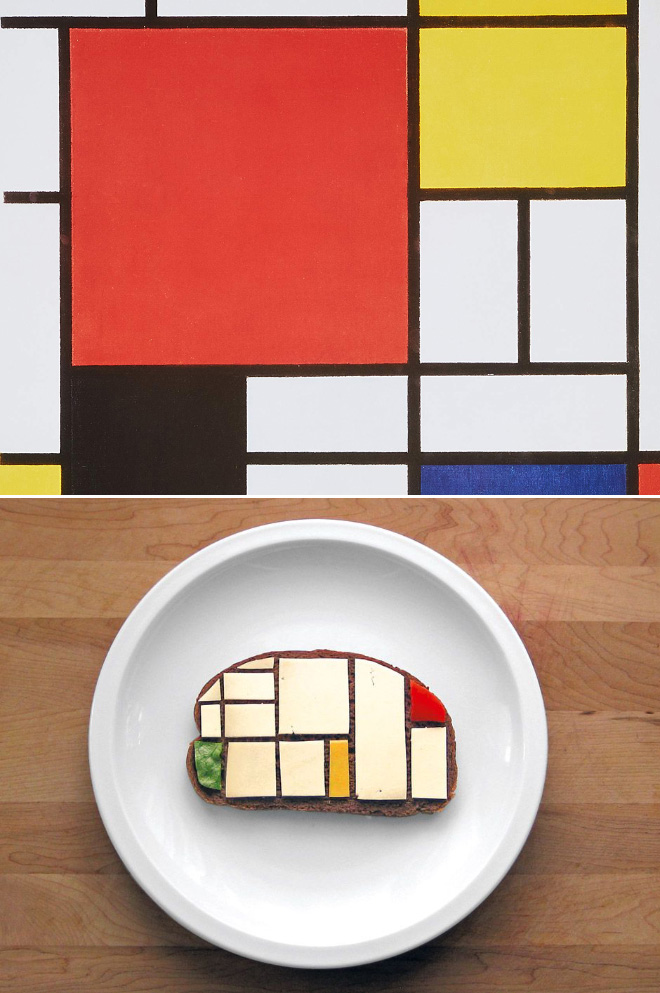

Like many institutions and individuals, the Annenberg also plans to increase their social media engagement. The Getty has already had a strong response to its call for people to recreate their favorite paintings at home via Twitter using #MuseumFromHome, while independent Instagram accounts like @hemapatel, @tussenkunstenquarantaine and @covidclassics have popped up with amusingly inventive recreations of famous works. “Even if we can’t be together physically, [art] can provide solace and reflection and humor,” Hollander said.

The glut of artistic responses shows how strong the desire to connect and create remains, even — or especially — in times of crisis. But, as several artists pointed out, this is only the beginning. The impact of the coronavirus, and the varied artistic responses to it, will continue to evolve.

Hebron found herself “bemused” by artists’ rush to act, saying, “I think they’re blowing their creative wads,” she said. “This is gonna be the reality for a while. We can take our time and work through it…and lots of amazing things will come out of it.”

While it is a powerful form of communication, art is not, in itself, a solution. For now, as Hollander said, and many echoed, “it’s a moment of humanity.”

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.