Yet the voice came, like mid-morning traffic streaming across U.S. 101, resembling the speech Steinbeck used to accept his 1962 Nobel Prize. Fuzzily remembered as a goateed, tuxedoed figure in a YouTube video, the legendary author’s disembodied croak channeled lines from The Grapes of Wrath (1939), his most famous novel.

“Once California belonged to Mexico and its land to Mexicans; and a horde of tattered feverish Americans poured in,” the voice rasped from an alternate universe — an America where labor and business once clashed regularly, and workers’ rights sometimes trumped money. “And such was their hunger for land that they took the land, stole Sutter’s land, Guerrero’s land, took the grants and broke them up and growled and quarreled over them, those frantic hungry men; and they guarded with guns the land they had stolen. They put up houses and barns, they turned the earth and planted crops. And these things were possession, and possession was ownership.”

Long unquestioned as the driving, exhortative values of Manifest Destiny, possession and ownership have been fundamentally transformed along Long Beach’s stuttering Atlantic Boulevard. On the lengthy low-rise strip, these now suspect convictions scan like exhausted ideals: ghostly, short-term rental versions of their former selves — once golden, now peeling Reagan-era slogans interrupted by a reality of empty storefronts and cash-and-carry liquor stores. Currently, at least, they appear entirely oblivious to past or present histories, generational thefts, David versus Goliath quarrels, and major and minor boondoggles.

But there, squeezed between desultory one- and two-story buildings — fronting, among other businesses, a laundry, a nail salon, a Mexican bodega — a black metal gate serves as an unsuspecting portal into another, far more idealistic space. Step through the side door of the corner beige stucco building and it’s possible to access an unlikely location brimming with creative fellowship: a place of history and ambition, but also, as Long Beach’s Museum of Latin American Art curator Gabriela Urtiaga eloquently put it, of gratitude and respect. Enter the studio of Mexican-American artist Narsiso Martinez, the creator of an epic series of portraits of U.S. farmworkers that has taken the art world by storm.

“When people see my work, I hope they see individuals who work in the fields — real people who are really at the frontlines of food production; as human beings who have dreams, who have families.”

Fresh off being awarded the Frieze Impact Prize, conferred by the Frieze Los Angeles Art Fair in recognition of “artists who contribute their talents towards issues of social justice,” the 45-year-old Martinez greets two friends and me at the entrance to the converted storefront that doubles as his home and studio. He is stocky and soft-spoken, bearded and modest. An artist not yet used to being interviewed, his lapel-grabbing art has made influential people like Ariel Emanuel sit up and take notice (the real-life Ari Gold of Entourage and brother to former Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel, Ariel is the CEO of Endeavor Impact and serves on the Impact Prize jury). Martinez’s highly in-demand paintings and sculptures have also cracked the collections of a growing number of major museums, among them the Hammer Museum, the Santa Barbara Museum, and the Orange County Museum of Art.

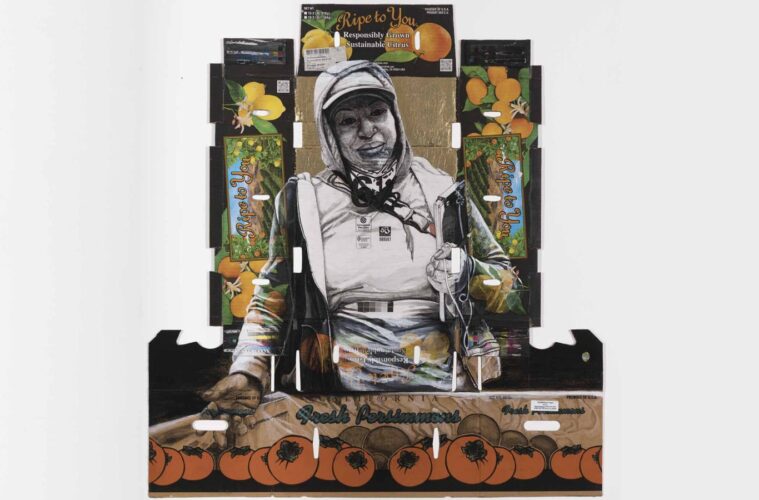

The Frieze Impact Prize endows an artist with $25,000 to create an important artwork. Martinez has titled his newest series Sin Bandana: 12 portraits of farmworkers done in ink, charcoal, and gold leaf. Drawn from his own experience as a farmworker, his pictures focus on people Martinez describes as “the men and women who toil in the fields picking the produce we consume.” Rendered on discarded produce boxes with the commercial graphics showing through, his hooded, open-faced likenesses provide a much-needed conceptual twist on textbook Social Realism. Besides making visible the nearly invisible onerous working conditions of the American farmworker, Martinez’s ex-voto-inspired pictures also channel Robert Rauschenberg’s liberating art-from-anything credo: “I think a picture is more like the real world when it is made out of the real world.”

“When people see my work,” Martinez says, “I hope they see individuals who work in the fields — real people who are really at the frontlines of food production; as human beings who have dreams, who have families.”

In describing his portraits of workers, Martinez is never far from describing himself. The Mexican American artist makes paintings of people he knows, often intimately, in various combinations of oil paint, ink, pastel, charcoal, and found materials layered atop flattened produce boxes that shill loudly for agribusinesses like Chiquita Banana and XL grocery retailers like Trader Joe’s. His specific subjects include, among others, his brothers, his nieces, his friends, but also an extended community of folks who, with a little imagination, stretch to encompass underpaid frontline laborers in fields such as health care, transportation, and food services. Besides painting individuals he routinely interviews in the process of setting down their likenesses, Martinez is firmly conscious of representing a larger reality — one that spans centuries as well as racial, ethnic, linguistic, and, above all, labor and class divisions.

“Today we call them essential workers,” he says about the roughly 2.5 million, largely disenfranchised farmworkers who put food on America’s tables. They do so while earning as little as $10 an hour and exposing themselves to grueling days, heatstroke, pesticide poisoning, and a welter of knock-on health issues such as cancer, asthma, and Parkinson’s disease. “If we actually mean that, then we really need them to have the same opportunities everybody else does.”

James Baldwin’s famous 1960s-era formulation comes to mind when considering poverty’s iron ceiling: “Anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor.”

After trying for years to enter the United States, Narsiso Martinez walked across the U.S.-Mexico border — from Tijuana to Tecate, California — at age 20. Following in the footsteps of his older brother, Juan, who had trekked northward to Los Angeles a decade earlier, Martinez saw opportunity in the kind of work most Americans consider beneath them. Like many immigrant stories, his personal narrative is driven largely by perseverance. Each time he tried to make it out of Mexico he plucked up his few belongings and his courage and struck out in search of what he has previously described as the basics of human ambition.

“It’s like a culture over there,” he told local Los Angeles PBS station KCET, recalling the October ferias, or hometown gatherings, where returning townsfolk show off the new clothes and wares they purchase with hard-earned dollars on the gabacho side of the Rio Bravo. Then, as now, he explains, “A lot of people don’t have TVs or bikes and beds. I grew up sleeping on the floor because we didn’t have beds, and a lot of people were like that. Just the idea of getting new shoes and nice clothes, maybe having a better home; that was the encouragement to go to the United States.”

Born in Santa Cruz Papalutla, Oaxaca — a town of 2,242 souls where just 48% of the population hold steady jobs, 50% don’t have indoor plumbing, and only 18% own a computer, laptop, or tablet — the budding artist grew up in a small house alongside his parents, four brothers, and two sisters. He remembers not owning socks to wear with his hand-me-down huaraches. The family owned a small plot of land, he tells me while proudly showing me around his spartan live-work studio. That is where they grew the majority of their staples, mostly corn, beans, and squash. “It was rough,” he says, “We were at the mercy of the elements, and we were hungry a lot of the time.”

“I grew up poor in Oaxaca. [My family’s] goal was to have enough to eat. We didn’t really have time to dream.”

The first inklings of Martinez’s future vocation arrived in what one might assume was the usual manner — in childhood encounters with paper and colored pencils. “I’ve always liked drawing,” says Martinez, as we sit on mismatched chairs in a room crowded with half-finished artworks, a table stacked with books, and postcards and clippings taped to the walls (among them is a Rembrandt self-portrait that hangs nearby in Pasadena’s Norton Simon Museum, a reproduction of a José Guadalupe Posada skull, and a blue Post-It note with the word “Wetback” written on it, along with a definition: “a Mexican living in the U.S., especially without official authorization”).

“When I was a kid I used to draw portraits for my neighbors,” Martinez continues, as I snap pictures of flattened cardboard boxes inside his home. “I also copied photos of celebrities from magazines, and images of cars and tools from catalogs. I stole the pencils and the pens from my father. We couldn’t afford a notebook, so I just used scrap paper.”

The cramped horizons imposed by being born impoverished in Mexico were obvious to him even during childhood (a recent study published by Mexico’s National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy [CONEVAL] estimates that 43.9% of the country’s population live in poverty). James Baldwin’s famous 1960s-era formulation comes to mind when considering poverty’s iron ceiling: “Anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor.” About the cruel disconnect between his youthful abilities and the adult realities available in his hometown, Martinez says simply: “I grew up poor in Oaxaca. [My family’s] goal was to have enough to eat. We didn’t really have time to dream.”

When Martinez made it to Los Angeles, his first ambition was to learn English. Within a week of his arrival he had matriculated in night classes at the self-described “World Famous Hollywood High” (notable graduates include Linda Evans, of Dynasty fame, and Warren Christopher, who, as Bill Clinton’s secretary of state, helped usher in the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA). His second goal, attending art school, had to wait till he found the means to manage more than a subsistence living in a famously hostile city. “I worked at a mechanic’s shop changing tires, but the boss needed me to work instead of going to night school.” After he switched to Evanston Community Adult School, in Los Angeles’s downtown, Martinez loaded and unloaded trucks at a plastics company. “It took me three hours to get to class in the morning, but I got my certificate,” he recalls. “Then I enrolled in a high school program for adults, which is how I fell in love with learning.”

Next, Martinez worked in a produce warehouse and bussed tables all over Los Angeles — restaurants in Santa Monica, Hollywood, West Hollywood, jumping from one eatery to another to grab prime shifts and attend classes. His family worried that he would never get married or have a family. In his mid-20s, he was resolute about wanting a career. Community college followed, then an undergraduate degree from California State University, Long Beach. While studying, a newfound American dream of becoming a math and science teacher appeared and vanished like a mirage.

“I was offered a paid assistantship in a biology lab, but couldn’t take it because I didn’t have papers,” he says. For consolation, he turned to an old Art 101 textbook. There he found a number of paintings of peasant subjects that proved galvanizing: Vincent Van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters (1885) and Jean-Francois Millet’s The Gleaners (1857) among them. “I was very disappointed [about not becoming a teacher],” he says, and asked himself: “What do I do now?” After poring over those master realists, he found an answer: “Here is a skill I can make my own,” he thought. “I can use it here, I can use it in Mexico, I can use it anywhere. It’s a way of seeing the world and it doesn’t matter what side of the border I’m on.” Soon after, Martinez enrolled in the MFA program at California State Long Beach.

Because of California’s AB 540 law, Martinez was able to scrimp on housing, food, and clothing for a time while still putting away just enough money for tuition. “I had no financial aid, and the DREAM Act had not passed yet,” he explains. (AB 540, signed into law in 2001, authorizes any student, including undocumented students, to pay in-state tuition at California’s public colleges and universities; a decade later, California enacted the California DREAM Act, giving undocumented immigrant students access to private college scholarships for state schools.)

The guileless expectations of straight realism fell like scales from Martinez’s eyes. “I didn’t have to draw the ranch owners because they were represented on the labels.”

Eventually, though, the burden proved too much to bear. Facing an especially brutal hand-to-mouth period, Martinez says he almost gave up. “I talked to my brothers, who were living in Washington State,” he recalls, with the expression of someone who has recently found their house keys. “They said that I should join them in the fields. They told me: ‘We’ll give you a place to live and you can save all your money,’ so off I went.”

For three summers running, Martinez worked the orchards and farms of Eastern Washington, picking cherries, asparagus, apples, and other produce from 1 a.m. to 3 p.m. for pennies a pound. Despite the backbreaking work, he quickly bonded with his fellow fieldworkers. He ate their food, slept in their trailers, and listened to their corridos. Soon he began sketching them, their faces and bodies, weather-beaten brown men and women who, while working, are covered from head to toe in hats, masks, and layers of clothing to keep away dust, insects, pesticides, and the sun. Hailing from Mexico and every region of Central America, his subjects took on discrete personalities in his sketches; in his mind, they slowly coalesced into a larger phenomenon.

As Martinez told Colorado’s High Country News: “I started to question the lifestyles of the farmworkers versus the lifestyle of the landowners and the ranchers. I started seeing and learning more about how, in the past, farmworkers were abused — how in the beginning the United States used Native Americans in the missions, and then used slaves. In the U.S., agribusiness has always relied on disadvantaged communities, so that they can make the most money out of it….”

In Los Angeles, Martinez struggled over how best to represent the people he had encountered. A large triptych hanging inside the Atlantic Avenue studio attests to an early attempt to capture fieldworkers in oil paint and canvas. A random trip to Costco proved a lucky advance on conventional materials. A colorful pile of cardboard boxes caught his eye while on a pizza run; he ferried some home and, unthinkingly, drew portraits on their printed sides. The result was pure alchemy. As he drew, a charcoal image of a farmworker layered over a multinational company’s fruit logo combined to reveal a third unexpected thing.

The guileless expectations of straight realism fell like scales from Martinez’s eyes. “I didn’t have to draw the ranch owners because they were represented on the labels,” he told KCET. “On the other hand, the whole agribusiness took shape through the labels, while the working class and farmworkers took shape as the marks I made with charcoal, colored pencils, ink, and gouache.” The rest, as they say, is history. But whose history, exactly?

“Before I decided to get truly political in my art, I would get critiques in graduate school about how I was making statements that were too social and political, so I decided to embrace it,” Martinez says, explaining how he has, through the use of the perfect found material, come to expertly address both art history and capitalized History. “After that, everything clicked.”

A work currently in the collection of the Hammer Museum, The Good Checker (2021), attests to the forthrightness of Martinez’s approach, but also to the subtlety with which he wields the seemingly simple mashup of paint, gouache, charcoal, and printed cardboard. A nearly life-size picture of a “field checker” layered atop a pair of splayed produce boxes — the artist describes “checkers” as quality-control workers who often “make the life of the picker miserable in the field” — the portrait conveys equal parts Diego Rivera hagiography and Kathe Kollwitz proletarian drama. Integrated seamlessly into a company-branded, responsibly-grown-and-sustainable thicket of lemons, oranges, and persimmons, Martinez’s female figure brandishes her fearsome clipboard like a scapulary.

A second painting, Hollywood & Vine (2022), drives home the need — the artist’s and society’s — to make visible the plight and humanity of farmworkers more emphatically. It depicts a squinting worker in an awkward sideways pose familiar to anyone who has ever been surprised by a friend with a camera. Materialized atop a colorful landscape of cheerful commercial designs sporting grapes and orange orchards, Martinez’s produce picker hides an additional piece of seething social commentary. Reflected in the subject’s wraparound shades is a lavish dinner party painted in the manner of a social realist “Where’s Waldo?” “Where are you in this picture?” it seems to demand, with an evenhanded nod to, among others’ unchecked privilege, California governor Gavin Newsome’s hobnobbing at the pricey French Laundry restaurant during Covid lockdown.

“Farmworkers pick the food and we get to eat it,” Martinez says. “Part of what my work is about is creating communication between the two sides. My work provokes questions — from viewers but also from the subjects of the portraits. People want to know about farmworkers, they want to learn their stories; farmworkers want to see their stories told.”

“When I first started making this work I was uncomfortable talking about politics and the plight of undocumented workers,” he continues, as the phone rings and our visit draws to a close. Martinez is working around the clock for a solo museum show and a gallery show, both scheduled for the spring. “I’m basically a very shy guy, but I’ve learned to become more vocal,” he tells me, with lingering modesty. “Now I embrace the injustice that affects farmworkers and my own situation.”

With Steinbeck’s voice still reverberating in my head, I ask Martinez if he’s read any of the books written by the Bard of the Dust Bowl. Because I assume his learning is overwhelmingly lived and hardwon, I’m startled by his response.

“I read The Grapes of Wrath recently,” he says, before delivering a firsthand précis on both fictional and real-life Joads. “One of the things that got me is that the corporatization he describes — small farmers losing their land to agribusiness, farmworkers losing their jobs, the development of GMO products, the environmental damage … that’s still the core of the story, how supply and demand operates. Basically, the more workers you have the less money you can get away with paying them. If you read Steinbeck you see that nothing has changed.” ❖

Christian Viveros-Fauné has covered art and its intersections with politics for the Village Voice and other publications for more than 25 years.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.