Painter Amir H. Fallah is the father of a young son, and they love to read stories together. Every culture has its own universe of children’s literature, from myths and fantasy to more quotidian fables and cautionary tales, cartoons, comics, and coming of age books that are all over the place for style and symbolism but have one purpose in common — to prepare children for what lies ahead of them in this world. Usually, these narratives try a bit to soften fears, encourage courage and forthrightness, and mostly have happy endings, or at least morals.

But something else is happening with these stories now, as Fallah experiences rereading them as an adult, knowing what he knows about life and love and loss and all of it, and it’s shedding a whole new light on how these stories function. Moreover, as someone who abides by a deep appreciation for what makes people interesting, unique individuals, Fallah has a whole other set of histories and perspectives, lived experiences of transcendence and injustice, and a hearty dose of political realism to layer on top of what he is currently teaching his son about the world. As the suite of large-scale paintings in Remember, My Child… suggest, this world is by no means a fairy tale.

Fallah’s acclaimed works of the past decade have reassessed what a portrait can be, how it is built, how it functions in art history and society. These works are known for figures shrouded in ornately patterned textiles which, like all the great many other objects which surround them in the compositions, belong to the sitters. You never see their faces, their skin is of indeterminate ethnicity, gender is not particularly revealed. In this way, an understanding of their history and personality emerges from the things which they have kept over the years, their lineage and memories and markers of turning points, their tastes. In this new series, Fallah removes the figure entirely, but each one or rather the totality of them all, is a dual portrait of himself and his boy. Instead of treasured possessions, the compositions build portraiture’s requisite sense of self through the languages — verbal and visual — of the formative stories they have been told, and are currently telling, about life, and about their own lives.

Amir H. Fallah, Remember, My Child (Courtesy of Shulamit Nazarian)

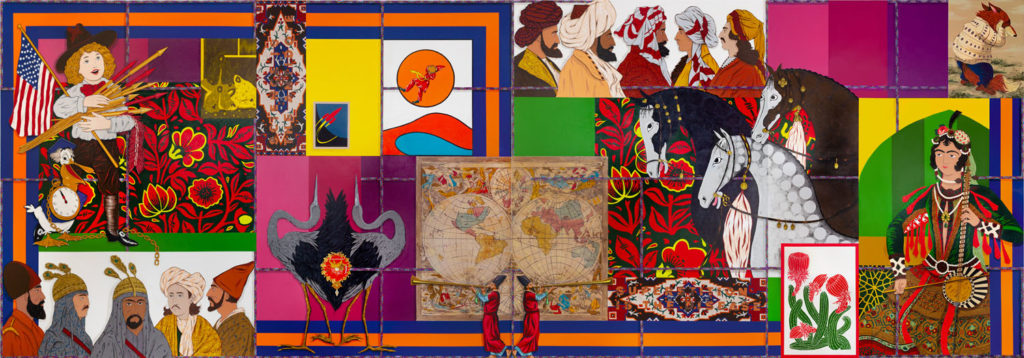

Fallah’s eclectic visual and narrative sources are culled from his own childhood memories of Iran, his family’s move to the U.S. during his youth, the good and evil which he subsequently discovered in American culture, the contemporary and classic children’s books that currently occupy his imagination, and a mindfulness toward how cultural values pass between generations. His penchant for visual bricolage and dynamic maximalism is fueled by an omnivorous appetite for high and low, kitsch and classicism, the cosmic and the commonplace. This juxtapositional aesthetic has been well developed in Fallah over the years, not least as publisher of the indie periodical and cult favorite, Beautiful/Decay. In fact, there is something of a magazine layout feeling to some of the larger compositions, as vignettes are compartmentalized by painted borders, and spaces flattened and laid like tiles.

The texts in each painting do a lot of the work of directing meaning, but across collections of varied iconography key cautionary themes emerge — the perils of racism, the denial of freedoms, the rejection of science, the desecration of nature, the quest for peace and justice, the evils of empire and greed. “They will smile to your face,” reads one. “Remember my child, nowhere is safe,” takes the breath away. “Science is the antidote, superstition is the disease,” reads another, even as one continues to pray.

Amir H. Fallah, No Gods, No Masters (Courtesy of Shulamit Nazarian)

Across all the works, archetypal symbols of wisdom, including actual wise men, proliferate alongside clowns and characters, caged birds and flowering vines, heirloom textiles, devotional architecture, maps and mosaics and animated creatures, dancing skeletons, and dances of the veil. “No gods, no masters,” reads one painting, and that’s it, that’s the message. The gods both old and new may or may not exist, but the parables imparted in their hagiographies contain essential truths worth salvaging. “No masters” is both a promise of freedom and an admonition against becoming an oppressor. In “Sentiment without action is the ruin of the soul,” Columbus falls off the edge of the earth, a wildcat surveys the land, a barnyard devolves into chaos, an iconic cowboy collapses in upon himself, as might America. This work surely imparts a message with resonance for the present moment, though seven might be a bit too young to join the resistance.

Shulamit Nazarian, 616 N. La Brea, Hollywood; on view through October 31; shulamitnazarian.com.

Amir H. Fallah, Science is the Antidote (Courtesy of Shulamit Nazarian)

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.