When the Fall 2020 school semester arrived this past August, it was a precarious time for parents across the country. Most of us had experienced the transition to remote learning at the end of the previous school year, but we remained hopeful for a return to normalcy for our kids and ourselves. After a long, claustrophobic summer, those hopes quickly faded away as Covid-19 infection rates continued to spike in Los Angeles and we prepared for a whole new year of virtual schooling. For many parents like myself, covid dangers meant missing out on graduation, as I did with my 8th grader at Thomas Starr King Middle School in Silver Lake.

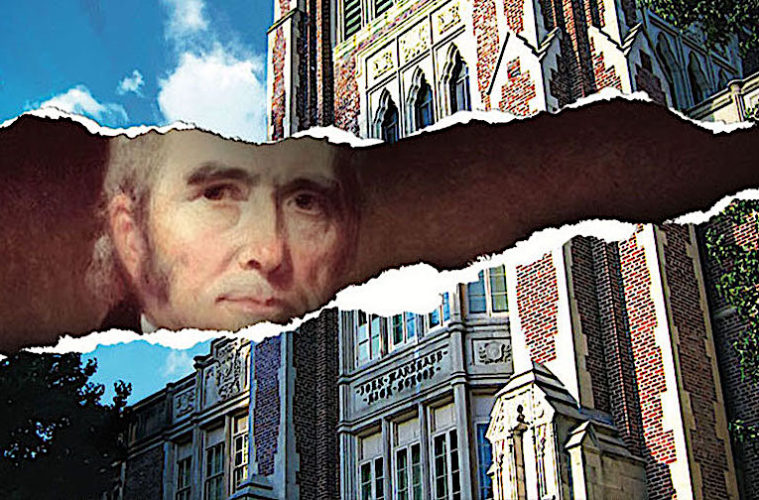

But the prospect of seeing my daughter attend my beloved alma mater – John Marshall High School – was a bigger deal anyway. Navigating the transition was challenging, though. After a somewhat confusing adjustment period figuring out classes and teachers via emails and the Schoology computer app, and a masked-up drive-thru event to pick up laptops and books for homeschooling (which was nostalgic for me as I parked in front of the very outdoor locker I used when I went there from 1984-1987), we have settled into the school year. It hasn’t been easy for anyone, of course, but parents of freshmen are in a particularly unique situation. Though my daughter is currently a Marshall student, she has yet to walk its halls or see her teachers in a classroom or sit at a lunch table as I did. She’s a high schooler who doesn’t know what high school is actually like.

“I think that we’re doing a little better than I would have imagined if you had told me before the pandemic that we would be 100 percent online without having time to prep,” Marshall Principal Dr. Gary Garcia tells us about how everyone’s adapted. “I think the number one concern is stress levels for students, parents, teachers and staff. Being a high school student is much more stressful these days … with the pressure to go to college, Advanced Placement classes, in addition to all the other stresses that adolescents have. And everything is exacerbated by the world of social media.”

Engaging restless teens, navigating online distractions (socials are indeed more important than ever as a means of expression and connection during pandemic) and pondering when in-person schooling should or shouldn’t resume has been on the minds of every parent, and in L.A., regular emails, calls and texts from schools superintendent Austin Beutner, along with emails and “Coffee with the Principal” Zoom meetings from Garcia for Marshall families, have been a huge help. The re-opening issue has made for contentious conversations all around the country, but the Marshall community has had another question to consider this semester. Issues related to racial inequity that had been addressed by Black students during the last school year have manifested post George Floyd and thanks to Dr. Garcia, a proposed change of the school’s name is on the table, garnering strong reactions that highlight the political divide our country currently faces.

Drive-thru book pickup this past August. (Lina Lecaro)

Do Your Homework

In late August, Principal Garcia recorded a “welcome” address and YouTube video for students and parents (accompanied by a written version) that was much more than an introductory greeting. It was meant to send “a clear message about race relations at our high school and the plan to address and reduce some of the tension on campus.” He saluted Marshall students who participated in peaceful protests against “the long-stand racial discrimination that Black people have faced since the founding of this country,” and he identified three areas for parents, students and administrators to focus on including banning the N-word from non-Black student use on campus (and social media) and a more inclusive curriculum with new ethnic studies classes and a literature course focusing on writers of color.

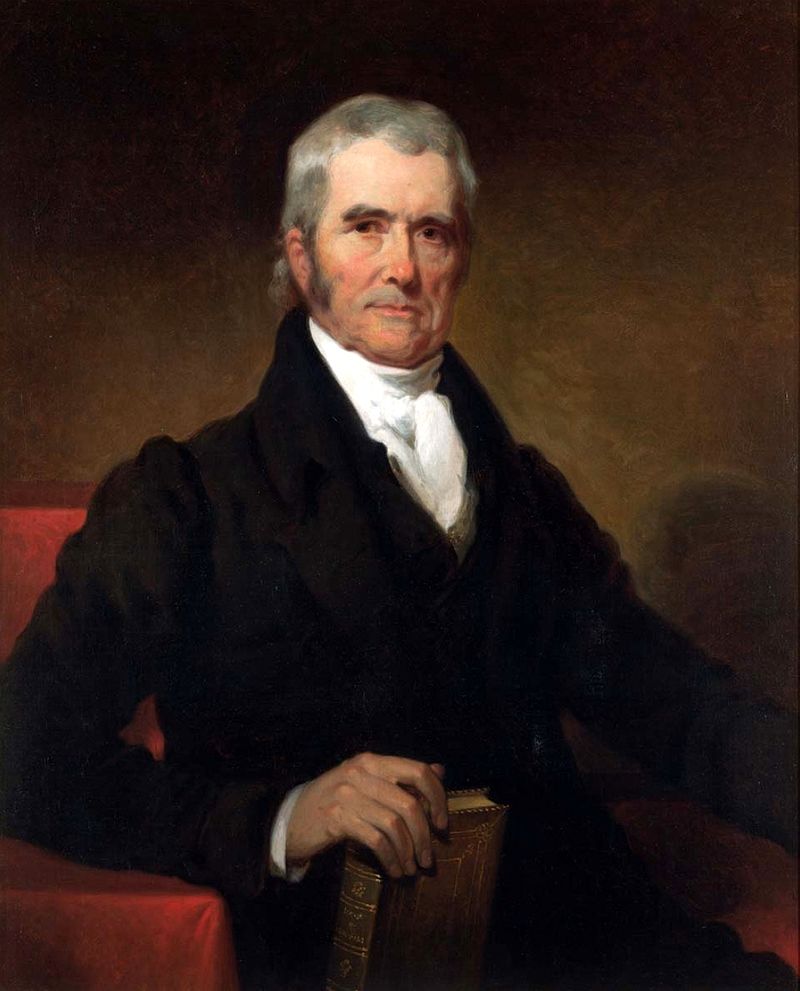

A couple months later, Garcia’s weekly email noted the name change proposal, citing John Marshall’s history with slavery. The fourth Chief Justice of the United States (serving from 1801 to 1835) owned slaves for most of his life and was said to have doubts about emancipation due to fears of a Black revolution. In terms of his rulings, his decisions are often cited but they veered differently case by case, with some serving to emancipate slaves and some not. Historians have noted that Marshall not only owned hundreds of slaves himself, but engaged in buying and selling throughout his life, influencing him to side with slave owners more often in court decisions.

In any case, the suggested name changes would not require much deviation from the school’s current moniker. The first option would change it to Thurgood Marshall, after the first African-American justice, whose seat was filled by Clarence Thomas after he retired during the Bush administration. The second option would ditch the “John” and change the name to simply “Marshall,” referencing no one person in particular, but maintaining the school’s identity as many call it that anyway.

“I was influenced by the courageous alumni at Jordan High School because they loved their school as much as the Marshall alums love their school,” Garcia explains, citing that institution’s removal of its original moniker “David Starr” Jordan, due to the Stanford President’s racially biased eugenic beliefs. (Stanford University by the way, recently announced that it too would be removing Jordan’s name from buildings as well as a statue of his mentor Louis Agassiz, a naturalist who promoted polygenism- the belief that human racial groups are unequal with some being inferior, a concept that was often used to defend slavery).

“The Jordan alumni understand that their identity, their history, their experience as Jordan students is not being erased or diminished because they aren’t calling it David Starr. In fact, they don’t want to be called David Starr. And that’s a major fallacy in the argument that some alumni are making – ‘I have so many experiences with Marshall from the ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘40s, whatever, and now you’re taken away my memory!’ Are you kidding me? How does that make sense? Your memories have nothing to do with the name of the school.”

Portrait of Chief Justice John Marshall (Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain)

Clashing Classes

Reaction to the proposal was swift. The “Official John Marshall High School Alumni” group on Facebook, consisting of 7.2 thousand members, has been a battleground ever since the change was announced, with former Marshall students from all eras posting opposing views on the issue daily and threads devolving into name-calling and insults to such an extent that the page’s moderators have threatened to shut down the group if it didn’t stop. Other Facebook pages covering Los Feliz, Silver Lake and Echo Park (including a neighborhood group with over 19 thousand members) have seen verbal spats about the topic as well. Those against the change have been especially vocal, suggesting, as Garcia referenced, that it would taint their memories and that doing so would be giving in to “cancel culture” and needlessly PC-minded views.

“Back when JMHS was built, there was no policy that stated you couldn’t name a high school after a slave owner. I don’t believe it’s a LAUSD policy now,” Kendall B. Jue (class of 1974), shares with L.A. Weekly. “I proudly attended JMHS, and I’m a proud alumni. No change in school name is needed, nor is it desired by the tens of thousands of proud alumni. A name change is only wanted by a very small minority.”

“John Marshall deprived his slaves of an education in order to control them,” counters Sherry Uyeda, who has been active in the Marshall group. “That very reason should disqualify him from having a high school named for him. And then there is the brutality, rape of female slaves, separating of families, prospering on the backs of the suffering, whippings, amputations, etc.”

While many say the past is the past and don’t seem concerned about John Marshall’s history with slavery, some who are against the change think keeping it can make for a teachable moment. Stephanie Lozano Sears, a 2nd generation alumni (class of 1983) is in favor of keeping it. “All my siblings also graduated from JMHS classes 85’, 92’, 95.’ Both my parents are alumni,” she shares. “We need to learn and if we don’t remember we’ll forget and when we forget, we do it again. Without the stairs of the past you cannot arrive at the future.”

“I do not believe that the time is right for the principal, Dr. Gary Garcia, to bring up the name change,” concurs almni member Joanne Kamiya. “Students are not in school. During a regular school session learning around this name change proposal could occur. History teachers could bring up questions to allow students to think about the time he was alive.”

As a member of the Alumni group who agreed with many of the arguments for the name change, I discovered that bullies still exist outside of high school (OK, I’m a journalist so I already knew that) but after reading every point of view, including pov’s and links about Marshall’s cultural significance, I see validity in both arguments.

The writer’s locker. (Lina Lecaro)

Still, talking with Garcia, who reveals that the idea was born after a coalition of Black students came to him with concerns about racism at the school, the case for change is compelling. And it is not new either. In addition to Jordan, Garcia also mentions Johnny Cochran Middle School, formerly known as Mt. Vernon (George Washington’s home) in L.A. as an example. Since our first president himself owned slaves, schools across the country are reconsidering being named after him too, including San Francisco where it was reported this past October that up to 44 names were being reconsidered following a San Francisco Unified School District panel deemed them problematic, stating that school names should not involve “anyone directly involved in the colonization of people, slave owners or participants in enslavement, perpetrators of genocide or slavery, those who exploit workers/people, or those who directly oppressed or abused women, children, queer or transgender people.”

It’s become a heated issue across political lines, too. In general terms, most Democrats tend to be for changing and removing names and statues to help right wrongs of the past, while most Republicans tend to be against it, calling it “erasing history” and insisting we can’t and shouldn’t change everything because of the feelings of some. In recent news, the annual defense spending bill, just passed by Congress last week, includes language about renaming military bases which Donald Trump opposes and was threatening to veto as of this writing. Most Marshall alumni don’t seem to be divided by obvious party lines, but ideologies on this issue do mirror the conflicted state of the U.S. after a summer of protest and post-election. As Los Angeles tends to veer liberal on these types of issues, the outrage this proposal has incited has been somewhat surprising but what hasn’t, is the deep connection to, and pride in, the school itself that so many still feel. To understand this, a bit more background must be provided.

GREASE (courtesy Paramount Pictures)

History in Session

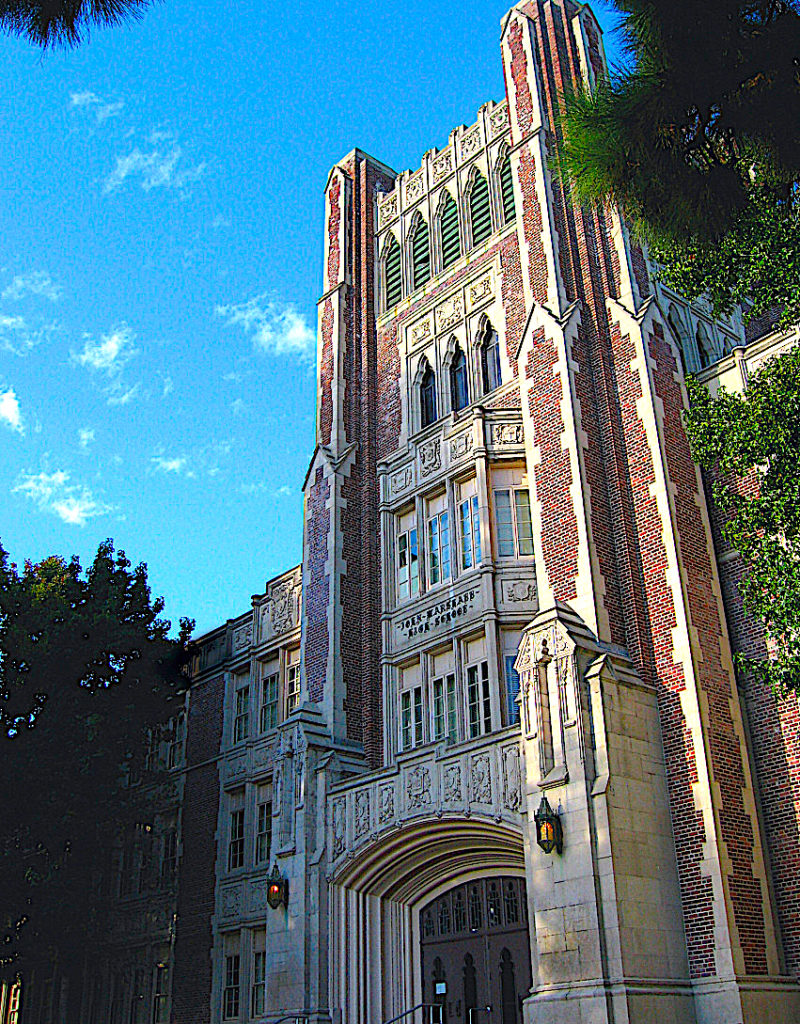

Constructed in 1930, Marshall opened the doors to its collegiate gothic style building in January of 1931. The school’s mascot, “Johnny Barrister,” was meant to reference the now-controversial justice, whose bust stands in the center of the Senior Court. Known as the Great Chief Justice, John Marshall was the principal architect of constitutional law in America.

The school became part of LAUSD in 1961, but 10 years later, it almost didn’t survive. After 1971’s Sylmar earthquake, parts of it were damaged and condemned leading to a “Save Marshall” effort that involved the local community and took years of structural work to be completed. By 1980, the beautiful landmark was fully back in business and its cathedral-like entrance became a frequent star of TV and film. Due to its convenient vicinity to the major studios it was, and still is, a go-to for location scouts in need of a classy, classic looking campus. Though repairs to the structure have been ongoing in recent years following decay and falling debri in the tower around 2012, a temporary scaffolding was erected and it remained open pre-pandemic.

Marshall has become one of the most recognizable campuses on film. The athletic field was seen in the 1978 classic Grease during the iconic carnival scene and climax in which John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John sing to each other on a funhouse ride and later fly off into the sky in a Grease Lightning-powered pair of wheels. In the ‘80s, several more unforgettable projects utilized Marshall’s campus to backdrop scholastic life, and I happened to be attending the school during this period. Following the filming of Van Halen’s “Hot For Teacher” video which not only featured the school’s front entrance as the kiddie rockers exited, but also the library for Eddie Van Halen’s solo scene, the entirety of the facility’s furniture was rearranged to capture the guitarist’s long walk atop a path of tables and desks. I saw the library disarray aftermath firsthand, though I didn’t get to see the legendary guitarist (who just passed away last month) himself.

The video was filmed and released in 1984, which was my freshman year (back then most high school’s ran 10th-12th grade versus 9th-12th today). That same year, Marshall was seen in the Tom Hanks hit Bachelor Party and the original Nightmare on Elm Street starring Johnny Depp. Two years later, it was the setting for John Hughes’ 1986 classic Pretty in Pink, with both the halls and exterior featured in scenes between star Molly Ringwald (Andie) and arrogant big man on campus James Spader (Lane). Other Marshall scenes in movies and film include Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Space Jam, Can’t Hardly Wait, The Wonder Years, Masters of Sex, Supernatural and School of Rock, to name a few.

The high school is clearly recognized and beloved for its role in pop culture, but for those of us who actually went there, there’s a sense of ownership that goes beyond the entertainment industry. Marshall was and is a melting pot in terms of ethnic makeup and backgrounds. As a Latina, I felt more welcomed than I did in middle school where I bused as part of the Magnet program to John Burroughs Jr. High in the Wilshire District. Marshall is now a Magnet school itself, and though the area has changed and gentrified, the student body appears to be as diverse as it was when I attended… well, from what I can see in my child’s Zoom sessions, anyway.

PRETTY IN PINK (courtesy Paramount Pictures)

Personally, I discovered my love of journalism at Marshall, working as Editor in Chief on the school paper, The Blue Tide, before moving on to attend LACC and then Cal State Northridge, while interning at L.A. Weekly (which had an office just up the street on Hyperion Ave). I also loved singing with the school choir and joined the theater department my senior year to perform in the Spring stage production, a daring version of the Tony-nominated Broadway musical called Runaways. It was a bold choice at the time, exploring the plight of homeless teens ravaged by prostitution and drug use, using swear words and provocative imagery, but no parents or students protested or objected. Marshall was always a very progressive place.

Two of my fellow theater students and friends (both class of ’88)- Lola Glaudini (Sopranos, Criminal Minds) and Autumn de Wilde (recent cover story subject and director of this year’s Emma), went on to achieve greater success in entertainment thanks to Marshall’s creative foundation, and they weren’t alone. In terms of successful alumni, the list is long. Leonardo di Caprio is probably the most famous (though he was already acting and attended sporadically), while Hollywood madame Heidi Fleiss was easily the most infamous. Black Eyed Peas members Will.i.am and Apl.de.Ap met while attending summer school at Marshall, while several sports figures and local politicians got their start there as well.

The Great Debate

Marshall graduate Pete Arbogast (class of ‘72) is best known as the voice of the USC Trojans. The son of late broadcaster Bob Arbogast (who also attended the school), this sports historian has been very active in the Marshall Facebook group since the name change conversation began.

“I think we should have a ‘John Marshall day,’ or weekend or month, and first teach who he was and what he was really like, then do community service in his name to show how the student body has been taught and learned to become better than our past,” he tells L.A. Weekly. “Removing the name would not allow for that teaching lesson to be carried forward. Leave it be, and act, as a whole, better because of the lessons he taught us through misdeeds of his life.”

Former L.A. City Councilmember Tom LaBonge has equally deep ties to Marshall. “I came from a family of eight sons, me being the seventh. My brothers Chris, Bob and Mark also went to John Marshall,” he shares. “For me, John Marshall was a special place. Many of my classmates went from Ivanhoe Elementary, King Junior High, and finally to Marshall, 1968 to 1971.”

As far as the name change, LaBonge seems to lean toward a compromise. “I’m a Barrister through and through,” he says. “I think the LAUSD should implement a comprehensive ethnic studies class for all students. If there is a name change, it should be a name addition, possibly: ‘John Marshall/Thurgood Marshall High School.’ Students should learn the history of these distinguished members of the U.S. Supreme Court and the time they served in our nation’s history.” He also thinks that “a lesson describing the current focus on American life, including the pandemic but more importantly, the social justice movements with Black Lives Matter,” should be implemented.

(Steve Meek)

Though the majority consensus on this issue is unclear, those who oppose seem to be more vocal as of late. Many simply feel it’s a question to address when school is back in session, in person. There is also the question of how much the name change might cost (some estimates indicate it could be as much as $300,000). Garcia has been the target of a lot of negativity since he announced the proposal, but the native Angeleno, who is in his 13th year as an L.A. principal (he was at Hamilton High School for nine and a half years, was assistant principal at Paul Revere Middle school for six years and has three-and-a-half years at Marshall) is holding steadfast in his belief that it’s the right thing to do, right now. “I felt that I had to strike while the iron is hot,” he says, heartfelt. “There is a new social conscience in our country and I very strongly believe that if I brought this up pre-George Floyd, I would have had a tougher time getting agreement. If we wait five years, this consciousness might die down.”

As for the students themselves, my daughter and her friends – some of whom say they plan to run for student offices – seem to be all for the name change, though a formal student poll has not yet been done. But whose decision is it, really? Garcia says the actual voting should take place “in January or early February,” following district protocol that includes a committee formation composed of certain stakeholders who will create a timeline for the process. “The idea is that we reach out to alumni, parents, students and staff. Those four groups are encouraged to vote,” he says, though no one will be checking eligibility per se as it will be all online, so feasibly anyone could vote.

In the meantime, Marshall students and parents have other things to focus on, like wondering when in-person school will resume, not catching Covid-19 as we wait for the vaccine, putting food on the table amid layoffs and furloughs, raising final grades before holiday vacation starts and figuring out how to fill the time once it does. Social media will surely be a big part of the latter. I’m frankly glad it didn’t exist during my time in high school, and though I’d like to tell my offspring that young people grow out of negativity they currently spew online when they grow up, the discourse that’s arisen among adults due to the name change discussion (not to mention politics, mask-wearing, business closures, etc.) has proven that to be false. I still have hope that the diversity of cultural perspectives can find some common ground, and I think what I learned at Marshall high school laid the groundwork to be a part of that. Hopefully, the same is true for its students today.

L.A. Weekly will continue to follow the Marshall name change conversation and questions about when L.A. schools should re-open as updates develop. In the meantime check for school news at johnmarshallhs.org/ and achieve.lausd.net.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.