It’s only February, but Alison Saar is already having quite a year. Accomplished as a sculptor, painter and printmaker, as of this weekend’s Frieze Los Angeles art fair, she will have striking examples of early (1980s) through brand new (2020) works across all those mediums concurrently on view in L.A. And this is very on brand for a member of the matriarchal Saar fine art family, as her sister Lezley has an acclaimed exhibition of paintings and sculptures on view at Walter Maciel Gallery (through February 22), and her mother Betye’s work is on view now at LACMA, as well as at CAAM alongside Alison in the landmark jill moniz–curated exhibition L.A. Blacksmith (through February 16).

Saar recently opened Syncopation at L.A. Louver, a selection of sculptures and especially prints spanning the decades and illuminating the special relationship between those practices as they developed for her in eccentric tandem. This weekend, Louver’s Frieze presence is devoted to a solo presentation of her newest sculpture and painting, with Chaos in the Kitchen. In certain important ways, Syncopation’s examination of Saar’s narrative impulses and the evolution and refinement of her thematic foundations around gender, race and transcendence form the perfect prelude to the striking, witty and rather in-your-face works coming to Frieze. But the show’s deeper dive into the scope of her printmaking deserves its own attention.

Alison Saar, from the Copacetic Suite (courtesy of LA Louver)

One compelling example is the “Copacetic Suite,” depicting musicians, neighborhood figures and historic places around Harlem, which came out of a commission for the Metro-North Railroad’s 125th Street Station in New York City. “I had done two bronze sculptures and then they were renovating their waiting room windows,” Saar explains. And so the new commission became 16 images installed like stained glass panels — immediately after which Saar realized she wanted a printed edition too.

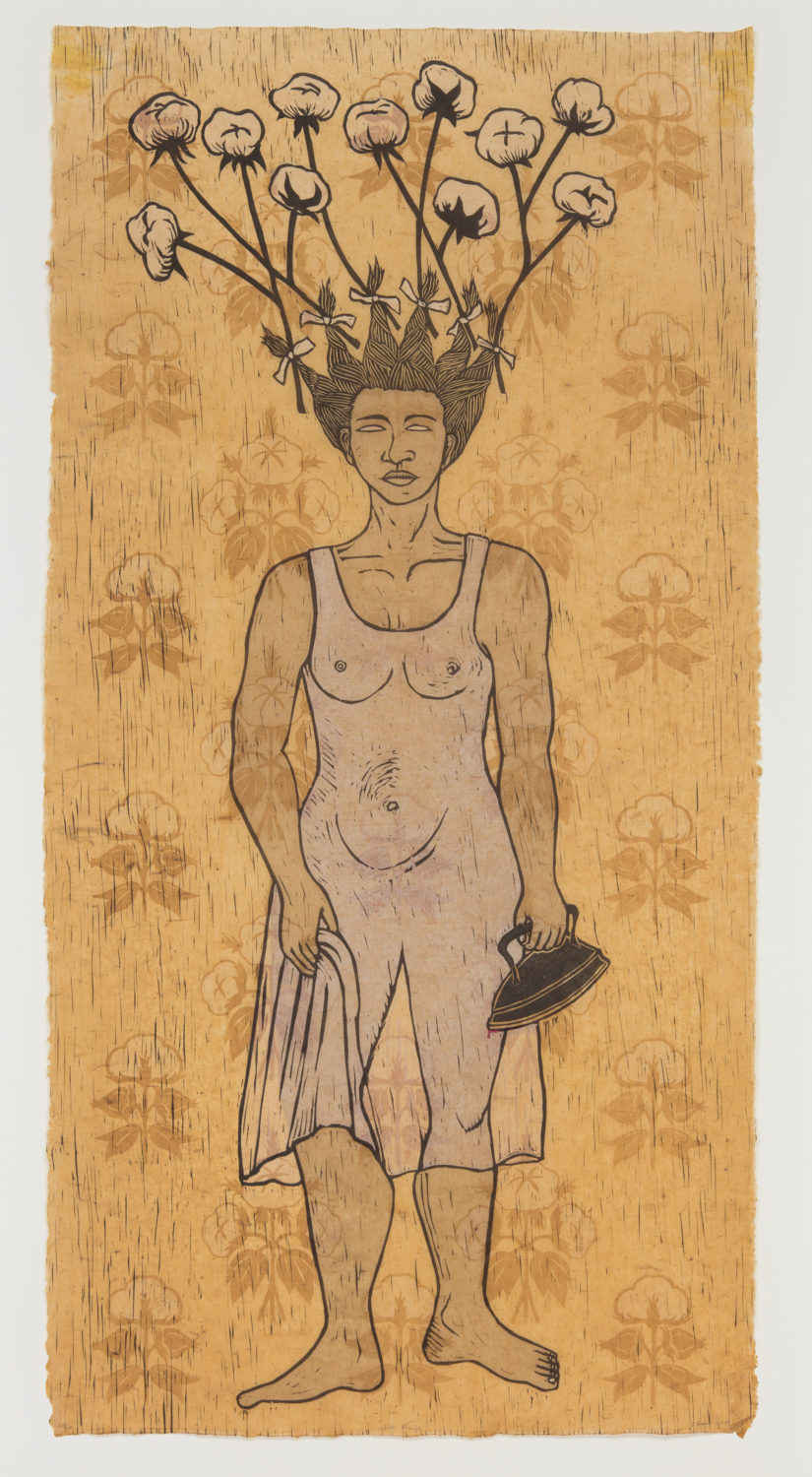

Alison Saar, White Guide (Courtesy of LA Louver)

Several more print-based works from the past decade are contextualized with several sculptures from the same periods, such as the clear relationship articulated between the print “White Guise” and the sculpture “Sugar Cane (Machete),” which both depict a version of the same strident, cotton-and-wire haired woman, grasping her weapon/tool and spiked with the powerful electricity of her circumstance. Though famous for her sculptures and paintings, Saar tells the Weekly how she “grew up around printmaking,” as her mother was and is a prolific printer as well as assemblage sculptor. Saar’s roughly 90 print editions represent collaborations with studios in different parts of the country, often made in direct relationship to sculptural projects, done afterwards like post-studies.

Alison Saar, Sugar Cane (Machete) (Courtesy of LA Louver)

As Saar frequently incorporates found objects like domestic equipment and household materials into her sculptures, she also does this with her printed matter. Works like “Redbone Blues” are executed on vintage handkerchiefs, which for Saar refers to associations of “this kind of refined garment with the lighter skinned black man and woman and how, if you had lighter skin, then you had more opportunities.” Another work, printed on burlap, combines railroad and commerce references and includes the phrase, “Stay alert. Stay alive.” which is not only a bit of workplace advice, and a commentary on darker skin and more labor-intensive occupations, but speaks to the present-day experiences of people of color in our unevenly policed society.

Other works employ unconventional cast-off materials like wood and metal as the hand-etched printing “plates” to make the marks. This is the same impulse that inspired an assembled wall sculpture from the ’80s, a three-quarter–scale dandy with style and swagger, constructed from vintage painted tin tiles. “When I first started living in New York City,” Saar recalls, “I loved the idea of a kind of magic urban folk shaman sort of thing. He’s conjuring a martini. And even though there are 30-something years between him and the Harlem portfolio, they belong together.”

Reconsidering another revenant piece, a sculptural bust painted bright blue and dating from the early ’90s, gave Saar reason to take stock of the role of color in her practice; most of her best known sculptures are bronze and patina, no primary chromatics.

“It’s interesting to go back and see that there was so much color and I used to have. And a lot more humor!,” she says. But color comes back in the new works planned for Frieze, in ways both subtle and strident. Not least as the presentation’s eponymous kitchen refers in large part to her own childhood, “because our kitchen was also my mother’s studio.”

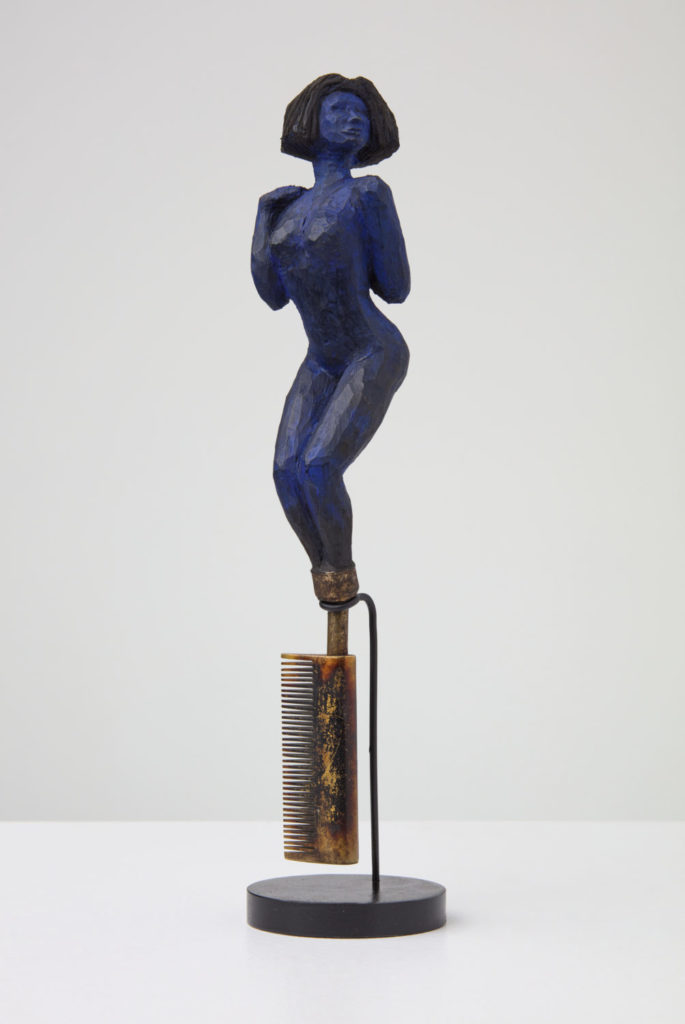

It was also the place where the kids’ hair got wrangled, and a new series of small sculptures of hot combs — metal tools for handling the girls’ unruly black hair — remains true to Saar’s operations along the narrative, symbolic, cultural, political, personal continuum. Starting with real antique implements, she replaces the handles with patinated sculptures of women, retaining the heft and intimacy of the functional original but sending its importance into a broader social arena. Assemblage always possesses the power of deeper dimensions because of all the history that comes with the energy of a well-used object.

Alison Saar, Hot Comb Haint Caldonia (courtesy of LA Louver)

“All of the handles are burned because you needed to put them on the fire or in the stove,” she says. “And I just love that sort of baptism by fire idea. We experienced this growing up and at the time it wasn’t fun for anybody, right? At my grandmother’s with my aunt, I’m sure we got burned behind the ears, and we also got smacked every time we would flinch because she didn’t want to burn us more. My cousins couldn’t go in the pool, because it was going to revert back and they’d have to start all over again.” And it’s still so front and center in our culture, obsessions about women’s hair, black hair, black women’s hair. Saar has made peace with this antique, but nothing that it’s about is truly over.

“Set to Simmer” is perhaps the centerpiece of Chaos in the Kitchen. While it continues with the theme of the wild-haired, infinitely wise domestic servant, repository of ancestral knowledge, mad kitchen skills and weaponized skillet, the woman in this work evinces a more confrontational energy. Her odalisque-like posture is both alluring and threatening; as she perches atop a dinner table, a single empty chair invites — dares, really — the viewer to have a seat and confront the reality of her there. With shades of Manet’s Olympia, her direct stare, her mirror made of cast iron, her leg crossed prohibitively, she too makes things uncomfortable for the viewer, challenging questions of agency and power. The table and chair are the same bright, deep red as the handles of the hot combs.

Alison Saar, Kitchen Amazon (courtesy of LA Louver)

In the sculpture “Kitchen Amazon,” a totemic figure wears a heavy belt of cooking tools and pots, along the lines of a construction worker but also evoking ceremonial African garments; the related painting depicts her skin in the same deep red as the painted wood in the table and comb handles. “Mirror Mirror” is a portrait in a cast iron skillet, making the conflated references to identity, skin, power, strength, self —and cooking — explicit again.

The catalog is a conceptual cookbook with family history, poignant stories, pointed wit — and real soul food recipes, too. “The kitchen is a place where everything happens in life, good and bad,” Saar says. It’s the literal and literary heart of the house, a perennial and perpetual metaphor for so much about how race, gender and power function in society. But at the same time we could make her gumbo, because it’s not just a metaphor but a lived truth. “It happens differently for us all, but it’s probably true of every single person in a way,” Saar says. “We figure out what we want in life while we’re making dinner.”

Alison Saar, Mirror Mirror (courtesy of LA Louver)

Syncopation is on view at L.A. Louver through February 29; Frieze Los Angeles is February 14-16 at Paramount Studios. For more information, go to lalouver.com.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.