A classically structured and refreshingly straightforward documentary film, Marcel Duchamp: The Art of the Possible in fact does the impossible — temporarily taming the wild, revolutionary, subversive intentions of this most iconoclastic of icons, just long enough to unpack and contextualize what all the fuss was and still is about.

Best known for instigating a kind of surrealist conceptualism that privileges the mind of the artist over the hand of the maker, Duchamp called for an upended populism that resulted in statements like, “When anyone can be an artist, then anything can be art,” and objects like “Fountain,” the infamous ceramic urinal signed R. Mutt and offered as modern sculpture. Like “Fountain,” Duchamp’s ideas went through cycles of early rejection, even scandalous critique, before their infectious excitement and the implications for a truly modern vision suited to the new post-war society took hold.

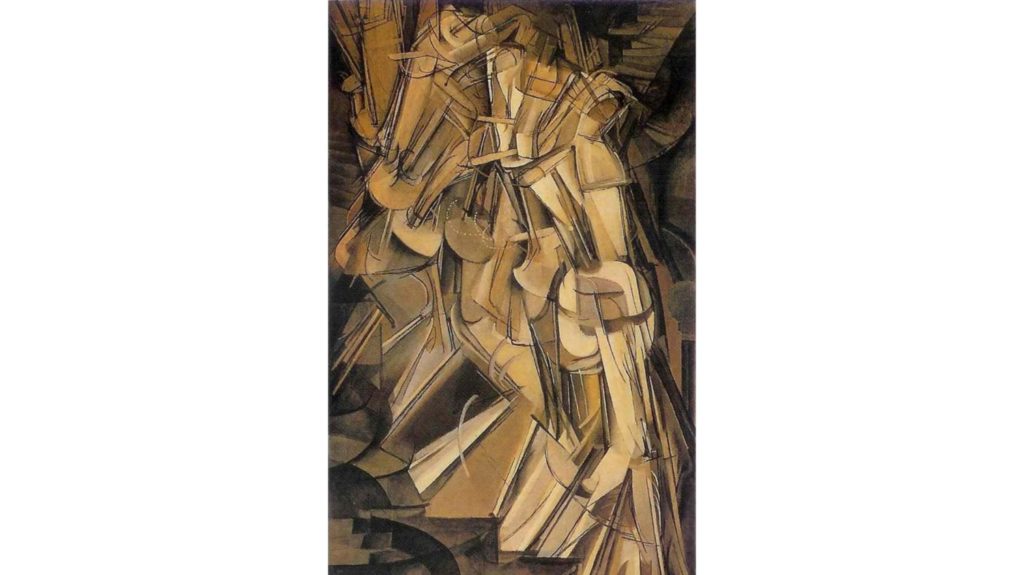

Such was the devastation in polite circles wrought by the mere appearance of his Cubist masterpiece “Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2” in New York in 1913, that in the social currency of the day, he was pilloried and mocked at a level befitting the recent Maurizio Cattelan banana incident at Art Basel. But Duchamp took this excitation as a compliment, declared it all a great success, and promptly moved to America, where he genuinely believed anything was possible — and it turned out, he was right about that.

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, 1912

He witnessed total acceptance and enjoyed something of a rock star status during his long lifetime (he died in 1968 at the age of 81), although he never relinquished his reputation as a provocateur. He followed up the “Nude” scandal with the “Fountain” situation in 1917, when he entered it in a competition as basically a dare to the petit bourgeoisie, whose rejection of his work surely revealed their own small-mindedness. Duchamp won that battle, and the piece launched his invention of the Readymade genre.

Ultimately, it’s not that Duchamp is anti-art, he’s just interested in relocating the assignment of meaning from the hand to the head. The documentary does an exceptional job of unpacking the arcane thought process of the revolution in creative thinking represented in this genre and its premise that the “art” exists in the choices and recontextualization of existing objects by the artist, not in the process of their actual making.

Duchamp interrogated issues of chance and authorship, likening art-making to science experiments, and positing uncertainty as a permanent condition and randomness as the underlying foundation of his conceptual model — although ironically he worked with slow deliberation and exceptional craftsmanship. Nevertheless, when “Large Glass/The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even” was cracked in shipping, he rightly declared, “Well, now it’s finally finished.”

In fact this belief that it was the audience who truly had the agency of co-creation to where nothing was really done until it was seen by another, was one of the most influential aspects of his philosophy. What Picasso or Pollock did for painting, Duchamp did for literally everything, from music to painting, dance, sculpture, and especially performance art and movements like Fluxus. An eclectic cast of art world figures that includes curators, dealers, critics, art historians and interdisciplinary artists like Michel Gondry, Jeff Koons, Marina Abramović (whose above outtake clip appears exclusively at the Weekly), Bibbe Hansen, Ed Ruscha, and David Bowie, each speak to the ways in which his ideas influenced them and indeed the entirety of 20th century western culture.

Watch the official trailer; find out more about the film; watch it on demand now. Directed by Matthew Taylor.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.