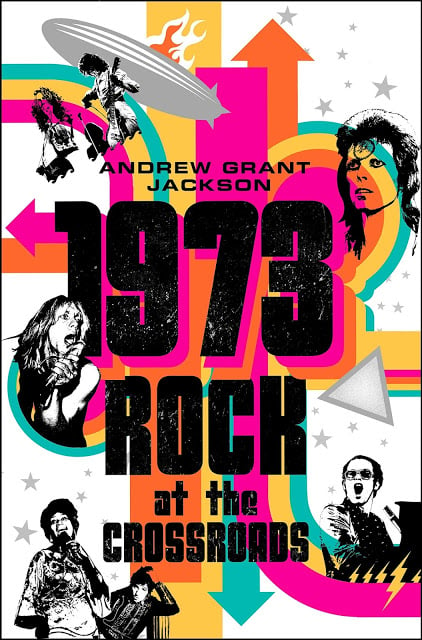

If the year 1969 marked the end of an era, just a few short years later an exciting new one was abloom, taking pop culture in unexpected new directions. In 1973, provocative new music genres (disco, punk) emerged as did some of the best classic rock compositions of all time, composed by now-iconic music artists. Arguably rock n’ roll was hitting a peak moment, with career defining works released by David Bowie (Aladdin Sane), Pink Floyd (Dark Side of the Moon) and The Rolling Stones (Goat Head Soup) to name just a few. You’ll get the scoop on plenty more in L.A. author Andrew Grant Jackson’s vibrant book 1973: Rock at the Crossroads which comes out today.

Chronicling the year’s biggest and best music moments, putting them in cultural context, and offering intriguing anecdotes, revealing and random facts and perspective on the significance of this important year in music, the book makes a case for 1973 as a turning point in entertainment. As he did with his previous book, 1965: The Most Revolutionary Year in Music, Jackson not only celebrates history and those who made it, but provides insight and details that any music fan will appreciate.

Below, an L.A.-centric except from the book concerning Tom Waits and the Troubadour in West Hollywood.

Jackson will be reading from 1973: Rock at the Crossroads at Book Soup tonight, Tues., Dec. 3, at 7 p.m. More info here.

(Thomas Dunne Books)

In San Diego, Tom Waits and Jack Tempchin knew they needed to get up north to West Hollywood’s Troubadour. The Byrds met there. The Buffalo Springfield did their first gig there. Elton John, Gordon Lightfoot, Joni Mitchell, Kris Kristofferson made their U.S. or L.A. debuts there. Lenny Bruce was arrested for obscenity there. Richard Pryor recorded his first live album there. Carole King played piano for James Taylor’s first solo gig there. They worked on each other’s albums and defined the singer-songwriter sound with session musicians known as the Section, a.k.a. the Mellow Mafia, including guitarist Danny Kortchmar and drummer Russ Kunkel, who also played on records by Jackson Browne, Linda Ronstadt, Joni Mitchell, Warren Zevon, Crosby and Nash. Kingmaker David Geffen checked out Monday open mic night, still called a hootenanny, to see who he could add to his stable. America’s third-bestselling single of 1973, “Killing Me Softly with His Song,” was co-written by singer-songwriter Lori Lieberman about the time she was blown away by Don McLean’s performance of “Empty Chairs” at the Troub.

So Waits said goodbye to San Diego and did in fact score a manager at a Monday hootenanny. “For a while there anyone who wrote and performed their own songs could get a deal. Anybody.”2 Jackson Browne recommended him to Geffen, who brought him to Asylum Records. “Jackson was Prince Charming to Tom’s Shrek,” said Ron Stone, who worked in the management firm that handled them both.3

Waits’s Closing Time, released in March, featured the ultimate “new Dylan” acoustic anthem, “Old Shoes and Picture Postcards”—bidding farewell to the girl crying in the rain as the road called him. “I Hope That I Don’t Fall in Love with You” could be a sketch of the Troubadour itself. The bar’s crowded, but the singer and the lady he’s watching from afar are both alone. He doesn’t have the guts to approach her, until he gets drunk, but in the third verse when he goes to make his move she’s already left.

When Waits recorded his hymn to his Buick Roadmaster, “Ol’ 55,” the session drummer got so swept up that he started singing along on the chorus.4 Geffen played it for Glenn Frey, who convinced the Eagles to cover it. Frey explained, “Your first car is like your first apartment. You had a mobile studio apartment! ‘Ol’ 55’ was so Southern California, and yet there was some Detroit in it as well. It was that car thing, and I loved the idea of driving home at sunrise, thinking about what had happened the night before.”5

Waits dug Tin Pan Alley as much as folk, like LA singer-pianists Randy Newman and Harry Nilsson, and used a stand-up double bass player and trumpeter. Rolling Stone called his album “all-purpose lounge music.” He was only twenty-three but wrote “Martha” as an older man calling up a long-lost girlfriend forty years later, both of them long married to other people. The echoey piano has the same 1930s Depression feel as Ironweed, the 1987 film Waits later acted in. It was a sepia-toned sequel to Jim Croce’s “Operator” after the singer wasted his life. At the chorus, Waits seems to be veering toward “Ol’ Man River,” but the string quartet swells and the song goes widescreen Technicolor. The ghostly chorale lifts the final chorus to an even more bittersweet plane.

As he prepared for his second album, he began to explore the down-and-out milieu more deeply. “He had all these cameras and he would go downtown and photograph the bums,” Tempchin said.6 New songs like “Depot, Depot” focused on the denizens of skid row to the accompaniment of woozy dive bar jazz.

He worked on new lyrics in the Venice Poetry Workshop, envisioning a concept album called The Heart of Saturday Night about the rituals of nightlife. It would open with a song about getting ready in the early evening and finish up “after hours at Napoleone’s Pizza House,” where he worked as a teenager.

The title track was an homage to Beat writer Jack Kerouac. Waits was inspired by a spoken word LP Kerouac cut, backed by Steve Allen’s jazzy piano. Waits visited Kerouac’s hometown in Massachusetts and hung out with Beat poet Gregory Corso. “Diamonds on my Windshield” was Waits’s On the Road pastiche, appearing both on Saturday Night and in the poetry magazine Sunset Palms Hotel. The same issue bore a cover painted by another major influence on Waits, Charles Bukowski, chronicler of Los Angeles barflies.

Just as Bowie had constructed a gender-bending spaceman persona, Waits created a retro beatnik bum pose to set him apart from his coke snorting, be-denimed peers at the Troub. “I’m getting pretty sick of the country music thing. I went through it, wrote a lot of country songs and thought it was the answer to everything. Anyway, so much of it is really Los Angeles country music, which isn’t country, it’s Laurel Canyon.”

He even bashed the band that gave him his first big royalty check, calling the Eagles’ version of “Ol’ 55” “a little antiseptic.” Soon he was sneering, “I don’t like the Eagles. They’re about as exciting as watching paint dry. Their albums are good for keeping the dust off your turntable and that’s about all.”

Years later, he conceded in Barney Hoskyns’s Lowside of the Road, “I was a young kid. I was just corking off and being a prick.”

He received his own brickbats when another Los Angeles iconoclast, Frank Zappa, asked him to open for him in November and December. Waits faced down Zappa’s notoriously belligerent crowd with just his guitar, piano, and stand-up bassist, forced to dodge more than his share of hurled fruit.

(Excerpted with permission by the author and Thomas Dunne Books).

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.