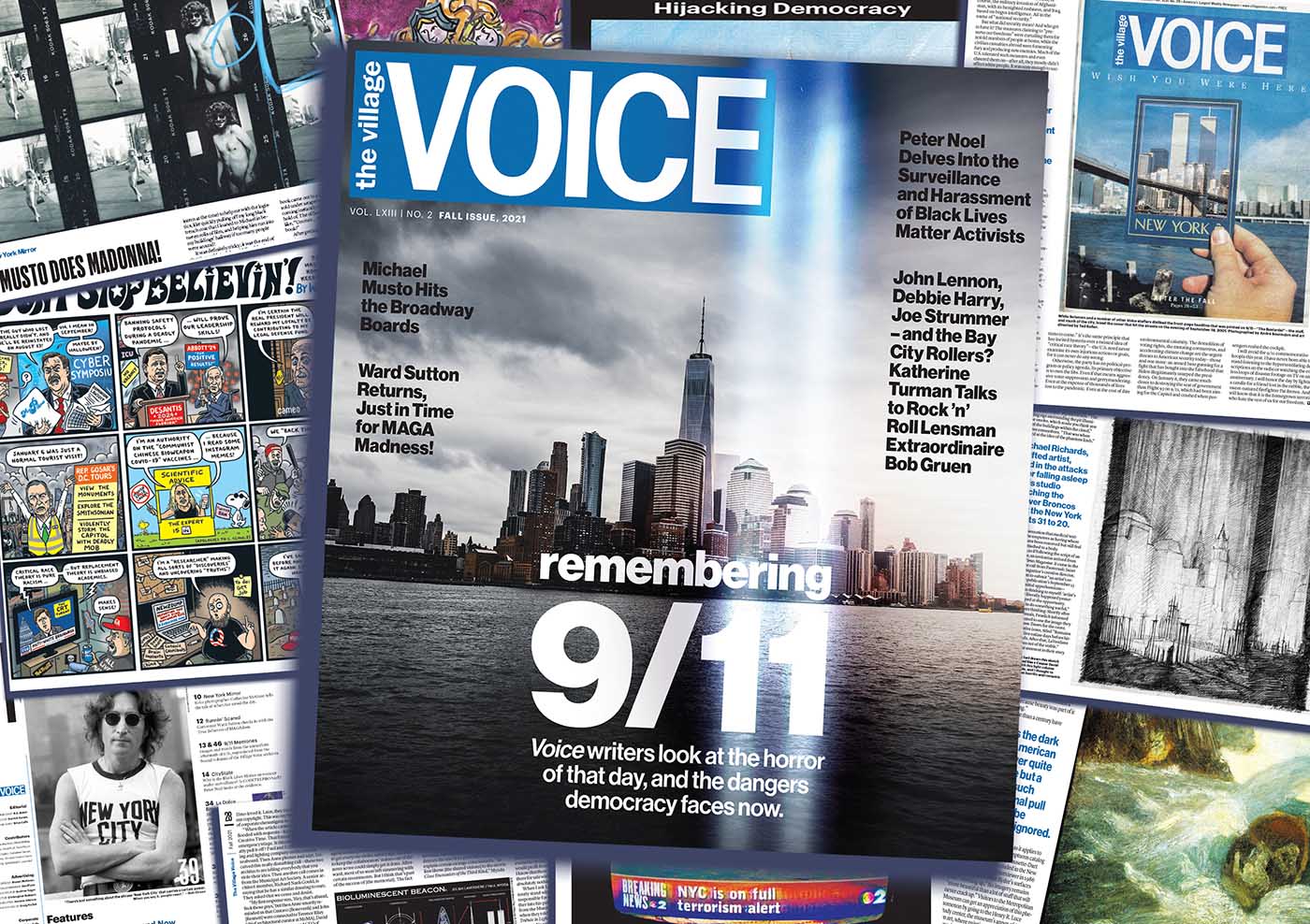

The Fall 2021 print edition of our sister paper, The Village Voice has hit the streets of NYC, filled with personal accounts of the 9/11 attacks and the fallout we’re still living with today, by Voice contributors including Alisa Solomon, Ross Barkan, Eileen Marker, Susan L. Hornik, Peter Noel, Ward Sutton, Katherine Turman and Michael Musto.

Read it all online at Villagevoice.com.

Here, Voice editor R.C. Baker recalls what it was like to cover the city in the wake of that horrific day and ponders the challenges and uncertainty democracy faces 20 years later.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, I was on a Long Island Rail Road train, waiting to pull out of Penn Station. I was sipping take-out coffee and going through page proofs for that week’s Village Voice (dated September 18).

This Tuesday morning train to the suburbs, a reverse commute, was never crowded. Then two women got on, obviously upset, saying that a plane had flown into one of the World Trade Center towers, and it was on fire. Oh my god, that’s awful, I thought. I knew that back in 1945, a B-25 bomber had hit the Empire State Building while flying in thick fog, and I assumed this was another such horrible accident. I went back to my page proofs. The cover photo depicted a pair of gloved hands on a chain-link fence, illustrating a story about an expected face-off between Washington, D.C., police and protesters at an upcoming International Monetary Fund meeting. As I was checking ad proofs (advertising paid the bills, so I scrutinized the latest Big Apple Futons ad for typos as closely as the cover), a disheveled office worker rushed into the car, gasping, “Why are the trains just sitting here? We need to leave! They’re attacking us!” He ran through the connecting doors toward the front of the train, seeming to want to get closer to Long Island. I figured he was a garden-variety mass-transit nutjob, and was relieved that he wasn’t going to sit next to me. Some minutes later, we came aboveground in Queens, near where I lived, and I registered with a shock that the guy who’d rushed through the train cars was no loony. Both towers were burning, and I realized that we were at war.

THE HORROR THEN: “WHAT THE HELL’S GOING ON?”

Cell phones were far from ubiquitous in 2001, but I had a company Nokia, a candy bar model. I pulled a laminated card of Voice emergency numbers from my wallet and called the editor in chief, Don Forst. No signal. A man asked if he could use my phone to call his wife. I handed it to him. He had no luck either. We took turns dialing. There was no signal when I tried calling my wife at our apartment in Long Island City. I dialed Don again. He answered. I told him that the hands climbing the fence for a protest in D.C. didn’t feel right anymore, with the city under attack.

An old daily newspaper guy, Don said something along the lines of, “Baker, you’re on your way to the printing plant. They’re plating up — it’s too late. We’ll cover everything next week.”

My fellow passenger called his wife. No signal again. Neither of us could get through. He said, “I gotta get off the train and go back,” and he did, at the next stop. Maybe, like me, he was reverse commuting and his wife was still in the city, and he realized his job on Long Island could wait. Mine couldn’t. My phone buzzed. Don said we were getting a new cover, and told me to find a page for a story. I told him there was a house ad for our upcoming Best of NYC issue on page three that could be killed.

“Good. I have a cover and full-page story coming.”

I tried calling the plant. Nothing. Many calls home went nowhere, until finally, one went through. “Hello?! Hello!?” We both started talking at once. My wife had seen the second plane hit while walking our dogs on the neighborhood’s East River pier. People had gathered to watch the first tower burn, but with the second explosion, someone in the small crowd said, “Everything’s changed.”

I got off the train in Farmingdale. The cabbie taking me on the quick ride to the Newsday plant, where we printed the Voice, asked, “What the hell’s going on? The radio says one of the World Trade towers is down.” I told him I didn’t know any details. He said it was terrorists, and I said they were certainly that.

As usual when I arrived, the final Voice plates were being processed. The press manager was not happy about holding some of their presses to wait for revised pages — Newsday was going to have many special editions to get out that day. Much yelling ensued, but printing the Voice’s 220,000 copies each week was an important commercial job, so they started running only the middle section, letting the two presses that ran our front and back “jacket” section sit idle when I promised it would only be 15 minutes. I’d been writing for the paper for seven years by then, and knew I was lying, and they probably did too, but they waited. And Alisa Solomon was a hell of a lot faster writer than me — the page came quicker than I could’ve imagined. The cover, too — with a photo taken by a man Alisa met on the street. No one remembers his name. Cary Conover, the photographer who shot the hands on the chain-link fence, remained credited for the cover on the Contents page. No one thought to change it. It was the only issue Cary ever had a cover credit for.

The new front page, when it popped up on a computer in Newsday’s production department, was a shock—a tight view of the second plane exploding, the moment everything had, indeed, changed. I was taken aback by the headline: “THE BASTARDS!” It seemed more a blunt exclamation along the lines of what Rupert Murdoch’s Post or the Daily News would come up with. But, like I said, Don had been in the newspaper business a long time — I wasn’t going to argue with him. While the new plates were processing, I called from Newsday’s landline and got through to my wife again. She had, after numerous attempts, reached her sister in San Diego and read off all the important numbers in our address book, so that friends and our far-flung families would know we were OK, and, as the crow (or jet plane) flies, some miles from the attack.

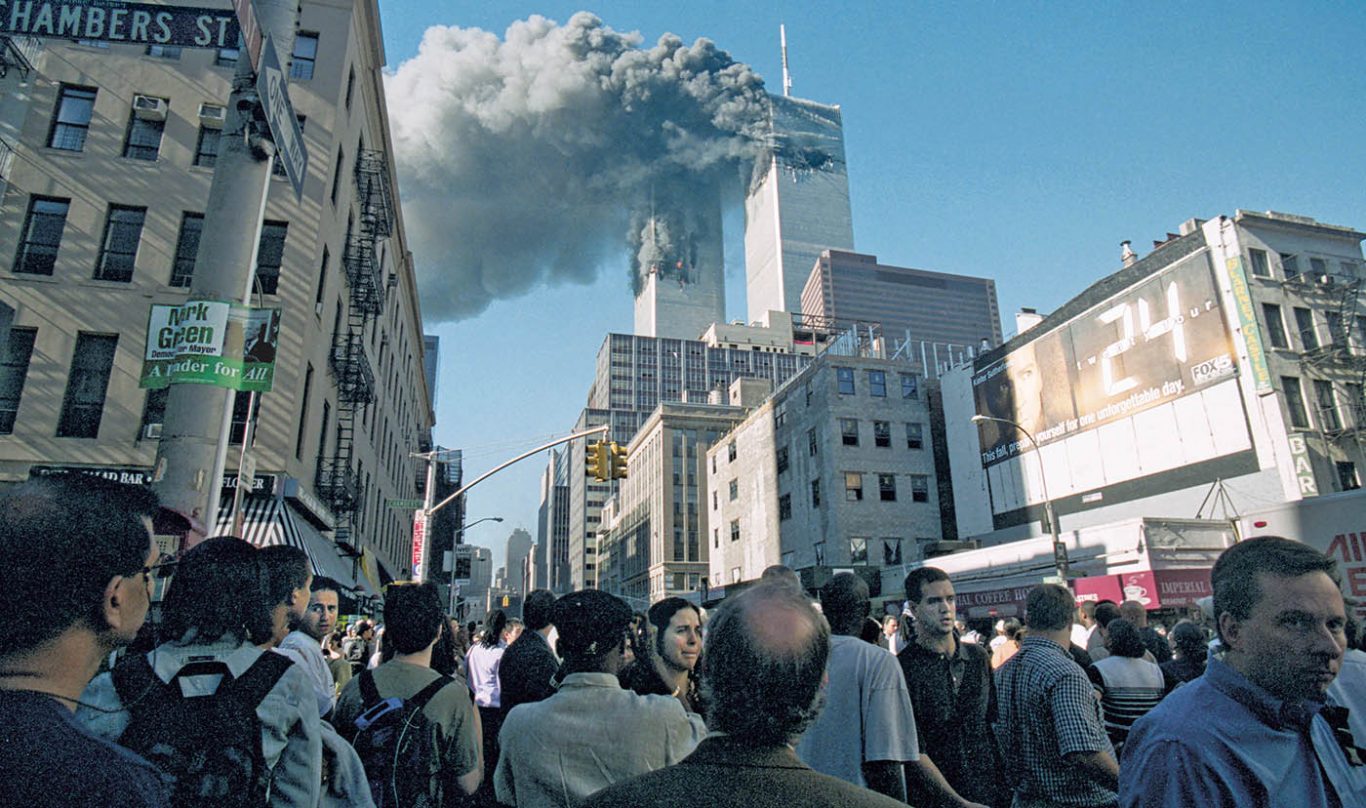

As the towers burn, citizens watch in horror or stream away from the carnage. Cary Conover’s picture captures much more than a thousands words’ worth of stories from that Tuesday morning, such as a campaign poster for Mark Green, an earnest mayoral candidate running in that day’s Democratic primary. With the pile of rubble burning downtown and dust clouding large swathes of the city, few would go to the polls, and their votes would not count anyway — the primary would be rescheduled for two weeks later and Green would go on to lose to Democrat-turned-Republican Mike Bloomberg in the general election. To the right, actor Kiefer Sutherland looks uptown from a billboard for a groundbreaking new action series coming to Fox: ’24.’ Because of the first episode’s climactic scene of an exploding airplane, the scheduled fall premiere was pushed back to November. The show was wildly popular, even if Sutherland’s Jack Bauer was quick to torture suspects to extract information as the show’s clock counted down to various apocalypses. Bauer’s excesses were decried by human rights advocates (though some admitted to loving the show) and professors who taught the law of war, one of whom said that while teaching that torture was ineffective, cadets at West Point would interject comments such as, “Yeah? Well, did you see Jack Bauer last night? He shot a prisoner right in the knee, and that dude talked.” Sutherland, for his part, opined, “It’s a television show. We’re not telling you to try this at home.” (Credit: Cary Conover)

As the pressmen locked the revised plates onto the presses, I read the proof of Solomon’s article. She’d been downtown when it happened, taking the visceral brunt of that second blast. I had been so busy, I hadn’t really experienced it. But Alisa had, and I was impressed with her presence of mind as she kept the bigger picture of American values in mind: “The terrible human casualties of today’s attacks haven’t even begun to be counted yet. Some of the intangible ones to come are obvious—the First Amendment, for starters.”

Then I got to work, checking all the presses. In retrospect, I was glad to have been busy with proofs and color registration and ink density all morning — it spared me from watching the towers fall over and over again on TV, a nightmarish loop too many friends and family later told me they regretted partaking of.

A few hours later, once the pressmen had zeroed in on the pages and they were all looking good, I went out to the loading dock, where dozens of skids were already piled high with thousands of copies of the 192-page paper. I was always impressed with the finished product, but on that day I felt doubly so. My last chore every Tuesday was to check with the dispatcher to confirm that the delivery trucks were on time. He shrugged and told me that the skids were just going to sit in the trailers in the parking lot; no trucks were being allowed into the city until further notice, though we might get some smaller vans into town by the next day. So I loaded up my laptop case and messenger bag with as many copies as I could carry, and one of the press managers gave me a lift to the train station.

I can still picture those long platforms, empty on the Manhattan-bound side save for me and maybe two other forlorn passengers. Across the tracks, I watched two trains disgorge frantic citizens who had been told — or just decided — to get the hell out of Dodge. I don’t remember if there were loved ones waiting and waving to them or not; I just remember the emptiness on my side and throngs like something out of a disaster movie on the other.

A couple of trains went past without stopping, probably to expedite getting the maximum number of folks quickly out of the danger zone. A man came up the steps, looked up and down the tracks, and said, “You see what those goddamn bastards did?”

“I did,” I replied. “And I got a couple hundred thousand copies of this going nowhere, but you certainly need one.”

I handed him a copy. “Yeah. That’s right,” he agreed. “Bastards.”

A train finally took me into the city, and then I walked from Penn Station to the Voice offices, in the East Village. Were the subways closed? Traffic stopped? Some things are crystal clear in my memory, helped by notes I made for a story that was never finished. Other details are as hazy as the acrid smoke that hung over the streets, getting thicker as I headed downtown. At 14th Street I had to show my Voice ID, with its Cooper Square address, to get past the police barricades.

I found Don and gave him a copy. He waved me his thanks because he was on the phone, already lining up some article for the next issue. Later in the week, I told him that I hadn’t been sure about his headline, but that going by the reaction it got on the train platform, his instinct was sound. He nodded. “That’s nothing. Wait’ll you see this week’s.”

Sure, I’m prejudiced, but no publication in the city or the nation came close to the bittersweet beauty of the Voice’s “Wish You Were Here” cover, the small subhead, “After the Fall,” adding to the sense of loss the city felt for those stalwart towers and all who occupied them. (See Alisa Solomon’s “Witness to the Fall,” in this issue.) Blunt and utilitarian, the World Trade Center lacked the monumental grace of the Empire State Building or the art deco élan of the Chrysler Building, but its sheer size made it a downtown beacon that instantly oriented tourists and more directionally challenged New Yorkers. Plus, its spectacular views of the metropolis were great for wowing out-of-town guests.

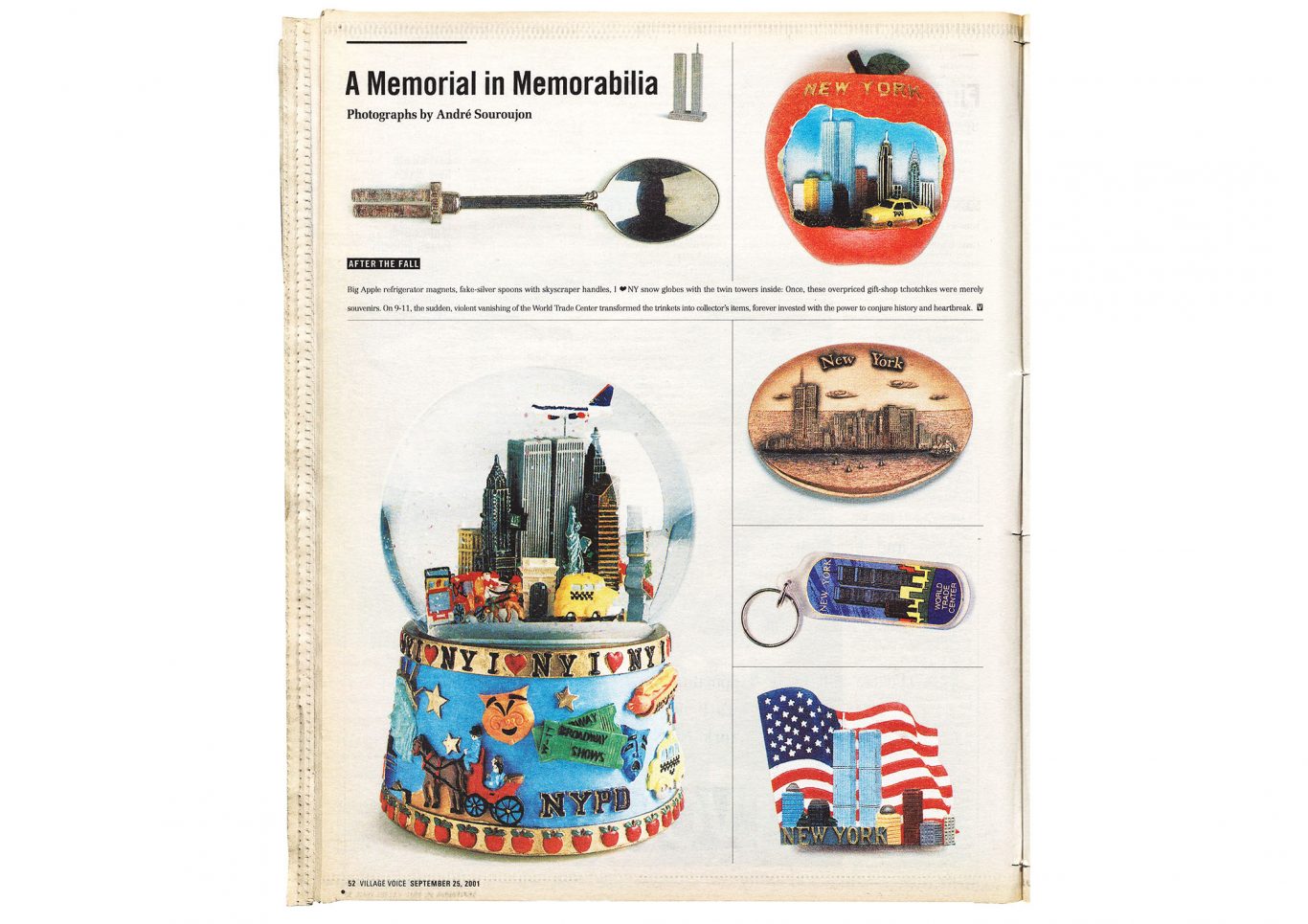

From the ‘Wish You Were Here’ issue: Baby spoons, snow globes, refrigerator magnets, key chains. The Twin Towers were gone, and all that remained were memories and tchotchkes. (Photographs by André Souroujon)

But there was so much more beyond the cover of that September 25, 2001, issue. Even as the wreckage downtown burned (and would, through December), Voice writers and artists grappled with the who, what, when, where, and, most crucially, the why of the attack. A photo of a face mask on the Contents page startles now, a portrait of PPE for workers toiling amid the atomized particles of concrete, steel, glass, plastic, asbestos, wood, paper — everything that constituted the skyscrapers and the people who had been inside them.

Turning the pages brought Nat Hentoff on the dangers of a new brand of McCarthyism rising from the WTC ashes, James Ridgeway on the coming quagmire in Afghanistan, Robin Holland’s portraits of first responders, Robert Sietsema on the resilience of immigrant shopkeepers, Kareem Fahim on the history of hate crimes against Arabs and Muslims, Lynn Yaeger on an even more surreal than usual fashion week, C. Carr on artists gone missing from their WTC studios, and so much more. Photographer André Souroujon lent gravitas to kitsch in his portraits of tourist-trap WTC tchotchkes. (He also took that issue’s cover photograph.) And then there were the columns of “missing” notices: “For Uncle Lee. 90th Floor, 2nd building. Did you make it? Still don’t know. We all cried for you today. I wait by the phone run run run faster please please you are strong just keep running. I hope you’re safe.” Six straight pages, bringing the flyers posted in bus shelters and on telephone poles and storefronts and construction fences all over town into our homes.

As the always insightful Richard Goldstein wrote in his piece about disaster movies coming to life, “Americans can tolerate a lot of things, but ambiguity isn’t one of them.”

THE DANGER NOW: THE “GRAND THEFT PARTY”

Twenty years ago, fanatics hijacked four planes and killed nearly 3,000 Americans. Some of the reasons that their leader, Osama bin Laden, gave for the attacks were “oppression, tyranny, crimes, killing, expulsion, destruction, and devastation” of Muslims around the world, coupling it specifically with U.S. support of Israel. Bin Laden was aided by the Taliban in Afghanistan, a regime that, as a recent Council on Foreign Relations report notes, was well known to have “neglected social services and other basic state functions even as its Ministry for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice enforced prohibitions on behavior the Taliban deemed un-Islamic. It required women to wear the head-to-toe burqa, or chadri; banned music and television; and jailed men whose beards it deemed too short.” Two decades later, the Taliban remains a brutal, and increasingly powerful, oppressor in Afghanistan.

Back in 2001, President George W. Bush saw things starkly, stating in an address to Congress shortly after the attacks, “They hate what they see right here in this chamber: a democratically elected government. Their leaders are self-appointed. They hate our freedoms: our freedom of religion, our freedom of speech, our freedom to vote and assemble and disagree with each other.”

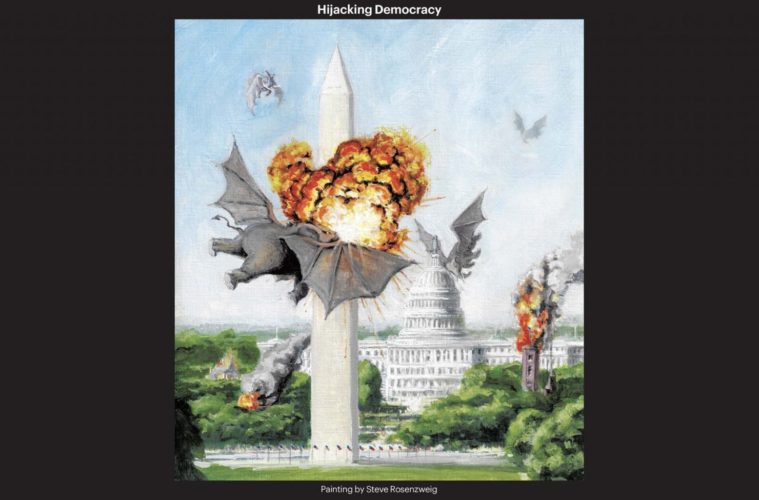

And yet, as devastating as the loss of life and sheer destruction was on 9/11, the planning had indeed come from “they,” from leaders outside of America. As the 20th anniversary of that terrible morning arrives, we can look back at a more recent attack on American soil, the January 6 insurrection at the Capitol. Videos and photos shot on that day — including selfies by proud insurrectionists — clearly portray a violent mob beating police officers, smashing windows, breaking down doors, and chasing lawmakers, staffers, and officers through the building in hopes of in some way overturning the lawful election of Joe Biden as president. This irruption of hate has deep roots in American extremism, whether the Ku Klux Klan’s post-Civil War legacy of intimidating and murdering Black Americans, the German American Bund holding a massive pro-Hitler rally in Madison Square Garden in 1939, David Duke building up a new “KKKK” (Knights of the Ku Klux Klan) in the 1970s, gun enthusiast Timothy McVeigh bombing a federal building in Oklahoma City (killing 168 people) in 1995, and on and on, right up to the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, which featured marchers proudly lofting Confederate and Nazi flags. President Trump famously said of the rally, where a woman was killed when a Nazi sympathizer rammed his car into a group of counterprotesters, that there were “very fine people on both sides,” a skewed sentiment when one side prominently displays symbols that, before they stand for anything else, are unabashed paeans to slavery and genocide.

But tyrants have always fostered hatred — it makes governing simpler when you can divide everyone into Us vs. an ever-increasingly demonized Them. In contrast, democracy requires the slow, steady work of consensus building, of horse-trading, of finding something in your opponents’ policies that you can accept. Authoritarians have no truck with nuance or understanding — only the maximum leader has the true answers to everything, and so is justified in sending followers out to intimidate, beat, and even kill political opponents. The supreme example is of course Adolf Hitler, who rose to power in an educated, modern democracy. But his Nazi party famously held representative government in contempt. As Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels said of Germany’s parliament: “We enter the Reichstag to arm ourselves with the weapons of democracy. If democracy is foolish enough to give us free railway passes and salaries, that is its problem. It does not concern us. Any way of bringing about the revolution is fine by us.” Later, he was even more sardonic: “This will always remain one of the best jokes of democracy, that it gave its deadly enemies the means by which it was destroyed.”

The Germany that turned to Hitler had suffered through the calamities of a lost war and economic depression. A passionate, scornful, and sarcastic orator, Hitler offered culprits for Germans to blame: the Jews, the Communists, the free press, and democratically elected lawmakers, as well as members of the intelligentsia — which was ultimately fortunate in that many skilled scientists fled Germany for America in the 1930s, a major reason that Franklin Roosevelt’s government, rather than Hitler’s regime, created the atomic bombs that ended World War II.

Donald Trump, while by all accounts not much of a student of history, grasps these tactics of division and the Big Lie — the repetition of a concept, however ludicrous, over and over until it builds to a chorus outshouting any opposition. The biggest and most insidious of Trump’s multitude of falsehoods is that he won re-election in 2020.

Such propaganda is nothing new for the former reality TV star. During the 2016 campaign, in an unprecedented provocation, Trump would not say whether he would accept the results of the election if he lost. Since his own polls showed him to be behind (he lost the popular vote by over 2.8 million votes), he was already promoting the idea that the election would be rigged. And he mocked centuries of precedent at a rally late in the campaign: “I would like to promise and pledge, to all of my voters and supporters and to all of the people of the United States, that I will totally accept the results of this great and historic presidential election — if I win.”

And remember that on the night of the 2018 midterm elections, results initially looked bad for Democrats. But as mail-in ballots were counted in subsequent days, a Blue Bust in the House turned into a Blue Wave (even a Blue Tsunami, depending on how a given pundit viewed the Democrats’ net gain of 41 House seats). Trump lost no time in attacking the validity of mail-in voting and impugning the competence of the U.S. Postal Service. A president who famously said, “I alone can fix it,” was never shy about attacking the capabilities of any person or institution. But of all the “stupid,” “fat,” “incompetent,” “wacko,” “dishonest,” “corrupt,” “mini,” “short,” “lying,” “evil,” “foolish,” “unhinged,” “sloppy,” “sleepy,” “little,” “low energy,” “failing,” “disastrous,” “begging,” etc., labels he tweeted at those he saw as enemies (many of whom once worked for his administration or his businesses), his most treacherous canard was calling Joe Biden a “Fake President!” on December 26, 2020.

Eleven days later, encouraged by Trump’s years of attacking election integrity and emboldened by a speech in which the president told them, “And we fight. We fight like hell. And if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore,” his supporters attacked the Capitol.

It has been widely reported that one student of history who did see this mayhem coming was General Mark Milley, chairman of the joint chiefs of staff. As Trump continued to spread the lie that the election had been stolen from him, Milley — like many citizens who were familiar with how Hitler came to power — saw the prevarications as laying the groundwork for a “Reichstag moment,” a reference to the 1933 burning of the debating chamber and gilded cupola of Germany’s parliament building. Hitler used the arson attack (which may have been perpetrated by his own followers) as an excuse to consolidate power through force, since his party constituted only a third of the seats in that body. Milley reportedly watched the January 6 uprising in disgust, and some days later, at a military drill in the run-up to Biden’s inauguration, said, “These guys are Nazis, they’re Boogaloo Boys, they’re Proud Boys. These are the same people we fought in World War II.”

A week later, Milley was sitting behind the Obamas at the ceremony, and has been quoted as telling the former First Lady that because of the peaceful transfer of power taking place before them, “No one has a bigger smile today than I do”—even if it couldn’t be seen under his mask.

But that smile might not last long if the Grand Old Party has its way in the coming years. The only thing that rose faster than racial and ethnic hatred during the Trump years was the bottom line of the super-wealthy, largely due to the Republican’s 2017 tax cuts, which, because they heavily favored the highest income brackets, passed with zero support from the Democrats. (In a recent Time magazine article, law professor Daniel Markovits points out that from March to December 2020, the richest 1 percent of Americans gained over $7 trillion of wealth while tens of millions of their fellow citizens lost income during a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic.) A long history of retrograde tax policies under GOP presidents provides more than enough reason to update the Republicans’ nickname to the “Grand Theft Party.” Yet inequitable monetary policy is just pocket change compared to the heist of our electoral system that the minority party has long pursued, by consistently seeking to disenfranchise voters who are not older and white.

Back in 1980, the extremely influential conservative activist Paul Weyrich told followers of what was even then a party made up mostly of straight, white, Christian voters, “Many of our Christians have what I call the ‘goo-goo’ syndrome: Good Government. They want everybody to vote. I don’t want everybody to vote. Elections are not won by a majority of people, they never have been from the beginning of our country, and they are not now. As a matter of fact, our leverage in the elections quite candidly goes up as the voting populace goes down.”

Considering that the Republicans have lost the popular vote in five of the past six presidential elections (W. Bush came in half a million popular votes behind Al Gore in 2000, but prevailed over John Kerry in 2004), Weyrich can be viewed as a Republican seer. Indeed, the GTP has long ruled as a minority party, through the lopsided force of the U.S. Senate. A Vox study last November calculated that over 41 million more Americans are represented by the 50 Democratic senators than by the 50 Republicans. In other words, if you vote in Wyoming, your ballot wields 68 times more power than if you’re voting in the much more densely populated California. One example of how this minority rule distorts the intent of voters: Brett Kavanaugh was appointed to the Supreme Court by senators representing only 44% of the American people. Earlier, Trump’s first pick, Neil Gorsuch, beat that low tally by one percentage point; senators voting for Amy Coney Barrett’s appointment represented 13 and a half million fewer constituents than those saying nay. The fact that Republican Senator Mitch McConnell nuked the filibuster rule for SCOTUS appointments to get Gorsuch through is another example of the Republican’s tyranny of the minority.

The Grand Theft Party, aware that it appeals to a shrinking demographic, is following Trump, their de facto leader, down the road of incendiary lies, which, unsurprisingly, has led to death threats against their adversaries. Election officials across the nation have received images of nooses in their emails; a 311 call in Philadelphia warned that election workers would learn “the hard way why the Second Amendment exists.” Joseph diGenova, one of Trump’s campaign lawyers, said that a federal official charged with overseeing election security should be “drawn and quartered” and “taken out at dawn and shot” for not backing Trump’s falsehoods about stolen votes. Of course, the lawyer later said that he’d been joking. Recall that Joseph Goebbels was always one for a good joke.

Beyond threats, GTP officials around the country are using the smokescreen of alleged voter fraud to pass restrictions on absentee voting, ballot drop-off locations, and polling times, seeking to drive down voter participation among the young, poor, non-white, and working classes. (Remember Weyrich’s formula: fewer voters = more Republican elected officials.) While Trump and his supporters crying election fraud have had more than 50 court cases dismissed since he lost, last November (none have succeeded), Republicans continue to seek end runs around democracy.

A new bipartisan organization, the States United Democracy Center, is warning of “a particularly dangerous trend within the larger voter suppression landscape: many state legislatures are pursuing a strategy to politicize, criminalize, and interfere in election administration. Their course of action threatens the foundations of fair, professional, and non-partisan elections.” Needless to say, the legislatures referred to are currently led by Republicans. The Democracy Center’s detailed report covers “sham ‘audits’ of voting results,” such as the one that has been stumbling along in Arizona for months, as well as “the wave of bills across the country that make needless changes to the design of our election administration systems solely for partisan advantage — a trend that jeopardizes the core democratic principle that elections should be a level playing field for all.”

As far as the courts are concerned, actual election fraud is exceedingly rare; this report and many others reveal how the GTP is “fixing” a problem that doesn’t exist, in hopes of sowing confusion and doubt about the electoral process itself.

Trump accomplished little that was positive in his single term, and has undermined his greatest achievement, the “warp speed” coronavirus vaccine, by rhetorically (and hypocritically, since he got the shot) siding with those who refuse to take it. His legacy is a party that is closer to a cult than a political organization — only two national Republicans, Representatives Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger, have spoken out with any consistency against Trump’s patently authoritarian, anti-American behavior. Add to that his penchant for attacking the competence of anyone simply doing their job — whether police officers, FBI agents, politicians, scientists, doctors, entertainers, athletes, election officials — if they disagree with him. His endless campaign of lies and division makes it so much harder for us to work together as citizens toward common goals.

It doesn’t have to be that way. Over the decades, I’ve worked with many pressmen (and they were mostly men) who did not agree with stories the Voice had printed. But they were proud craftsmen, and the skills of a few have stayed with me. There was one guy who would take nail clippers to the guide notches of all the plates going onto a particularly worn print cylinder, in order to ever so slightly shift the printing dots for better color registration. Another used an array of tiny shims that he would stick to the backs of plates to similarly nail the color. Then there was the PIC (pressman in charge) who cursed the whole time about what a pain in the ass I was looking over his shoulder, even as he obsessively adjusted the press’s water levels to get deep, rich black tones without the ink showing through on the opposite sides of the thin newsprint. Too often the guys were just printing tomorrow’s fish-wrap, but they took genuine pride in showing me how great they could make the Voice look.

A decade or so after 9/11, I was watching copies of the paper coming off a press at the rate of nearly a dozen per second. I was complaining to one of the press managers about a page that was remaining stubbornly out of register. He took the paper from me, and I followed him up the chutes ’n’ ladders catwalks to where he used a wrench to make a minute adjustment to a bolt I could barely see, buried as it was under a layer of dried ink and paper dust. Next time I looked, the page was tight as a drum. The man was a mechanical wizard, somehow keeping the press’s thousands of moving parts perfectly synchronized to maximize the quality of every issue, whether it was a 40- or 140-page edition. I enjoyed working and talking with him, even though we were political opposites — he was always happy to inform me that my newspaper’s opinions were crap.

He was also the first person who ever said to me — I think it was in response to an article about the upcoming 2012 election between President Obama and Senator Mitt Romney — that conservatives like him needed “to take America back.” I replied, “Do me a favor. Please don’t do it until I’ve got this issue onto the trucks.”

And he laughed. We both did. A decade ago, we could. Because we respected that we were both serious about our jobs, and just trying to make a buck.

Back then, America was big enough for both of us.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.