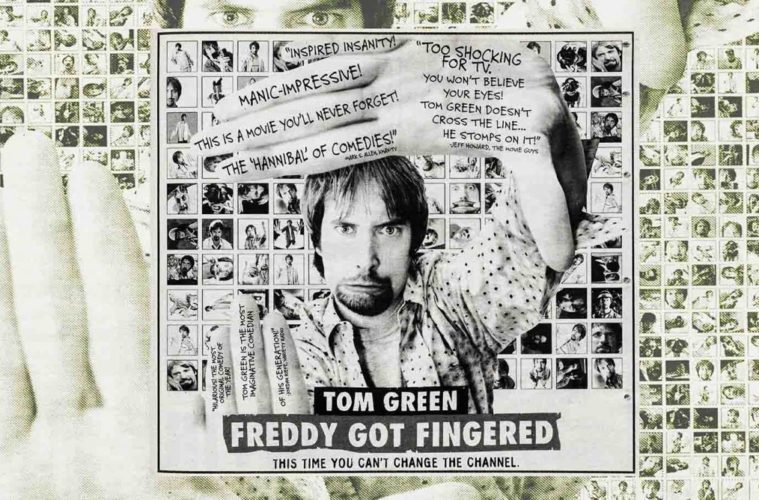

Do you remember Freddy Got Fingered? Think 2001, a TV trailer with sausages on strings and Tom Green mashing a keyboard, liltingly singing, “Daddy would you like some sausage?” Rotten Tomatoes: 11%. Winner of 5 Golden Raspberry Awards. Zero out of four stars from Roger Ebert.

Green started out on Canadian public television before being picked up by MTV, where he hosted an eponymous variety show, interviewing guests, presenting musical groups, and starring in gonzo man-in-the-street interviews and hidden-camera segments — such as asking people to help him out of a sidewalk trash can. His most pungent pranks were reserved for his parents, including leaving a severed cow’s head in their bed (his father was a big fan of the Godfather franchise) and installing a statue of them in flagrante delicto on their front lawn. (Green père angrily stomped it into ruins on-camera.) When Green was diagnosed with testicular cancer, he devoted an episode to a silly but informative medical documentary on the experience.

In Freddy, Green plays Gord Brody, an aspiring cartoonist with a decent sense of visual design and an awful personality. Leaving his hometown of Portland, Oregon, to pursue an animation career in L.A., he lands a menial job at a cheese-sandwich factory, but he soon melts down and abruptly ends up back at home with Mom and Dad. Gord’s father, Jim (an animalistic Rip Torn), crashes Gord through walls and destroys home and property in a series of slapstick sketches, as Gord hones his artistic skills and enters a bizarre and uncomfortable romantic relationship with Betty, a wheelchair-bound amateur rocket scientist (Marisa Coughlan) who enjoys having her paralyzed legs whacked with a bamboo stick as foreplay. In a moment of petty spite during a family counseling session, Gord falsely accuses his father of molesting his brother, the unfortunate Freddy, ruining his father’s name and condemning his 25-year-old sibling to confinement in the Institute for Sexually Molested Children. Enraged with his eldest son’s malevolence and frivolity, Jim smashes down the door to Gord’s room and tears up his drawings.

Broken, Gord abandons his aspirations and gets a job at a sandwich shop, his earlier factory experience a resume booster. While working, he sees Betty on a TV news segment: she has invented a rocket-powered wheelchair. Inspired, Gord doubles down on his animation efforts, selling a cartoon based on his family’s baroque dysfunction to an animation studio. Enthralled with the neanderthal brutality of the Jim character, the studio cuts Gord a $1 million check and commissions a show. The third act rockets off the rails, with Gord squandering his new fortune on jewels, helicopter rides, and airlifting a portion of his parents’ house, complete with tranquilized father, to Pakistan. This impresses Jim with its scope and expense, leading to an understanding between father and son after several more vulgar sketches and misadventures in the Pakistani underworld.

Green competently assembles a young-man-with-a-dream comedy-with-a-heart, but substitutes schadenfreude and gross-out gags for heartwarming moments and narrative payoff. Some scenes are funny in a straightforward way, but pick up guilty giggles when recognized as slices of genre parody sandwiched between awkward and/or disgusting humor. At his strangest, Gord pretends to be other people, making up fantastical lies and erratically pivoting to new characters mid-scene. The joke, unstated, is that Gord is mining responses from the other characters to these inventions for his animations, researching them in the vein of Jane Goodall’s observing apes in the wild or Truman Capote’s plunge into the minds of murderers.

The original critics of the film 20 years ago were unforgiving of Freddy’s baser aspects. About a quarter of the screen time, mostly frontloaded, is viscerally queasy, like a challenge issued to the viewer. There is probably a small but relevant demographic who think Tom Green jerking off a horse or chewing on an umbilical cord is hilarious, but such outrages are no doubt the biggest contributor to Ebert’s zero out of four (though no less a comedy luminary than Chris Rock has listed Freddy as one of his favorite movies).

Green revels in the quirks of human behavior and uses the looney tunes combustion between Gord and Jim to drag viewers viscerally through the plot points. Torn channels the animus of a silverback suburbanite, ready to tear his house apart barehanded if that’s what it takes to get Gord out of the nest. Torn’s face contorts with crinkly eyes and a face-cleaving grin when he believes Gord’s lie of finally getting a job, and then twists with growling pain and fury when he finds out he’s been had.

Twenty years ago, Village Voice reviewer Jessica Winter noted Green’s genealogical descent from camp provocateur John Waters, terming Freddy “a frat-boy remake of Pink Flamingos.” Overall ambivalent, Winter wondered if fans of The Tom Green Show might feel something missing from the scripted film. Pranks that would be shocking as candid scenes on his late 90’s MTV show are instead rehearsed and shot with actors and scripts, pulling the stakes up and out from Green’s brand of humor. Yet Green, in his directorial debut, delivered a faux inspirational comedy — young misfit achieves his dream — while simultaneously blowing up the genre at every plot turn.

Eric Andre is Green’s most visible modern-day descendant. Green’s MTV pranks and gross-out humor gave license to Andre’s man-in-the-street sketches and antagonism toward his guests. Andre’s newly released film, Bad Trip, is shot almost entirely as candid camera spots, using a small, in-the-know cast and leaving supporting roles to unsuspecting strangers caught on film. At its best moments, good samaritans become integral characters and gasping crowds lend action scenes more oomph. Too often, though, scenes fall flat by railroading the unsuspecting bystander through highly contrived sequences to encourage predictable responses of disgust and outrage, conjuring a malaise of hushed perplexion in the unwitting background participants.

British comedian Sacha Baron Cohen’s two Borat movies, released in 2006 and last year, respectively, offer another vision of candid gotcha elements. The original Borat is perhaps the flagship film of its genre. Unknown enough to blend in, Baron Cohen’s Borat is initially able to charm his way into upscale events as an affable foreign journalist, before snowballing into increasingly offensive behavior at his hosts’ expense. Borat 2’s more elaborate plot is forced into heightened contrivance compared to its predecessor. Much like Bad Trip, it is tortured with the main characters’ desperate attempts to elicit the correct candid responses, as well as with heroic post-production editing.

Freddy’s scripted nature avoided the desperation of trying to piece together candid scenes. The cast and crew focused on precisely executing the script, aesthetic, and tone. What emerges, while ramshackle on the surface, hits crisp and astringent as smelling salts. The coarser nature of media in the internet age may also make some of the more awful aspects of the movie feel almost quaint now (as if there were anything left to shock us in 2021). For every sense-assaulting transgression in Freddy Got Fingered, one can find plenty worse in Game of Thrones, which, larding portentous gravitas over its gore and cruelty, eschews even the hope of a cleansing belly laugh.

Green has stated that although the studio was originally supportive, cuts after focus testing were responsible for some of the characteristic abruptness of the film. For instance, originally, the L.A. sandwich factory that employs our hero was owned by Gord’s Uncle Neil (Stephen Tobolowsky), and Gord traversed an arc of dissatisfaction (including an I Love Lucy-like assembly-line fiasco) before purposely sabotaging his job. Yet this plotline was almost totally excised, because, as Green revealed in an interview last year, a scene of Uncle Neil kissing his male lover tested negatively for teenage boys in the focus group. Hence, Gord’s tenure at the sandwich factory devolved into a confusingly abrupt morning of tomfoolery before his leaving without a word — or a narrative motivation.

Over the years, Green has indicated that he would like to do a director’s cut closer to his original vision, but that he doesn’t have the footage. He has also let his fans know that the best way to support his dream would be to contact New Regency or 20th Century Fox (though a now-closed 2015 Change.org campaign garnered just 85 supporters). In 2019, Fox’s stake in these companies was sold to Disney. So if you want to see the director’s cut of Freddy Got Fingered, mount a social media campaign aimed at the descendants of Uncle Walt. After all, what could be a better homage to two decades of internet vileness than to see Freddy get fingered on Disney+?

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.