By now, the Korean New Wave is almost so grafted onto global mainstream culture, it’s sometimes difficult to remember it as a wave at all. Waves, in any case, age and mutate like we all do, and national zeitgeists are merely, in the end, the aggregate energy of their individual auteurs, who routinely outlive and out-career the hoo-haw of the new-wavey moment. So though today South Korean culture is everywhere, if mostly as a virtuosic variety of audiovisual junk food from Netflix on down, we still have the initial wave’s Fab Four, each now in their third decade of moviemaking. The high-octane genre machines of Bong Joon-ho have gotten the most global love, with the clockwork Grand Guignol launches of Park Chan-wook running a close third. The prolific neo-Rohmerian vexed-relationship dramedy of Hong Sang-soo, on a much more modest and yet much more prolific scale, has carved its own niche in international arthouses and streaming platforms.

The fourth major voice is easily the least congenial, and so the least known: Lee Chang-dong, whose films are prickly dramas of incendiary familial and social cataclysm, emotionally on fire and yet often mysterious and overtly poetic in their narrative fallout. You could say it’s part of Lee’s brand, inflicting ferocious pressure onto both his characters and his audience’s expectations of narrative neatness, seemingly encompassing an exhaustive fourth act where an ordinary film would’ve briskly settled for three, routinely marching past where Western filmmakers would go, into a netherland of psychosocial damage. Lee has directed only six films in 27 year. Starting out as a novelist and poet in the ’80s, he’s as much a writer as a director, his movement’s Cassavetes or Pialat, whipping up ultra-realist emotional cyclones while seething with judgment about contemporary Korean culture — its disaffected youth, its hollow commercialism, its class combat, its disconnection from humanist values. In fact, Lee’s closest contemporary among living filmmakers may be Turkey’s Nuri Bilge Ceylan, their films representing something of a frontline of a reigning 21st-century art-film mode: lengthy, thorny, uncomfortable, character-based-yet-character-agnostic, dramatically inconclusive, and alchemic.

Lee has always been a principled leftist, and was even effectively blacklisted between 2010 and 2017, by two consecutive conservative governments. (The scandal, involving a 60-page document listing over 9,000 names of artists opposed to the regime, who were consequently put under state surveillance, barred from receiving state subsidies, and, in some cases censored altogether, helped to bring the Park Guen-hye administration down.) But only occasionally have Lee’s films been overtly political — most famously, Peppermint Candy (2000), the touchstone movie for an entire Gen X cohort reexamining modern Korean history amid the late-century democratization efforts of President Kim Dae-jung.

That film bruisingly intersects with 20 years of social upheaval, including the military crackdown responsible for the infamous Kwangju massacre of protesters, in 1980, but does it in reverse. We begin in the present, as a disoriented man commits suicide in front of his old schoolmates, then leapfrog backward through time, tracing regressively the life of the dark-hearted hero (Sol Kyung-gu) from the wasteland of the present to his life as a neglectful husband and brutal cop to post-schoolboy innocence. (“Gigantic history,” a Korean undergrad of mine wrote in a critique of the film a few years later, “As either an assaulter or a sufferer, individual’s dream, related to historical swirl. It is not a special story, but the general hope that people have living in the end of the century. Where is the person not distorted and not wounded?”)

You hardly have to be a native to feel the movie nailing a particular generation’s outrage and guilt to the town-square wall for all time. It’s a scathing critique of an entire generation of Korean men, as well as of the country’s institutional default settings as it transformed itself into a democracy, but because it’s Lee’s film, it is Peppermint Candy’s ineluctable shape and pounding melancholy that leaves an ax gash on your memory.

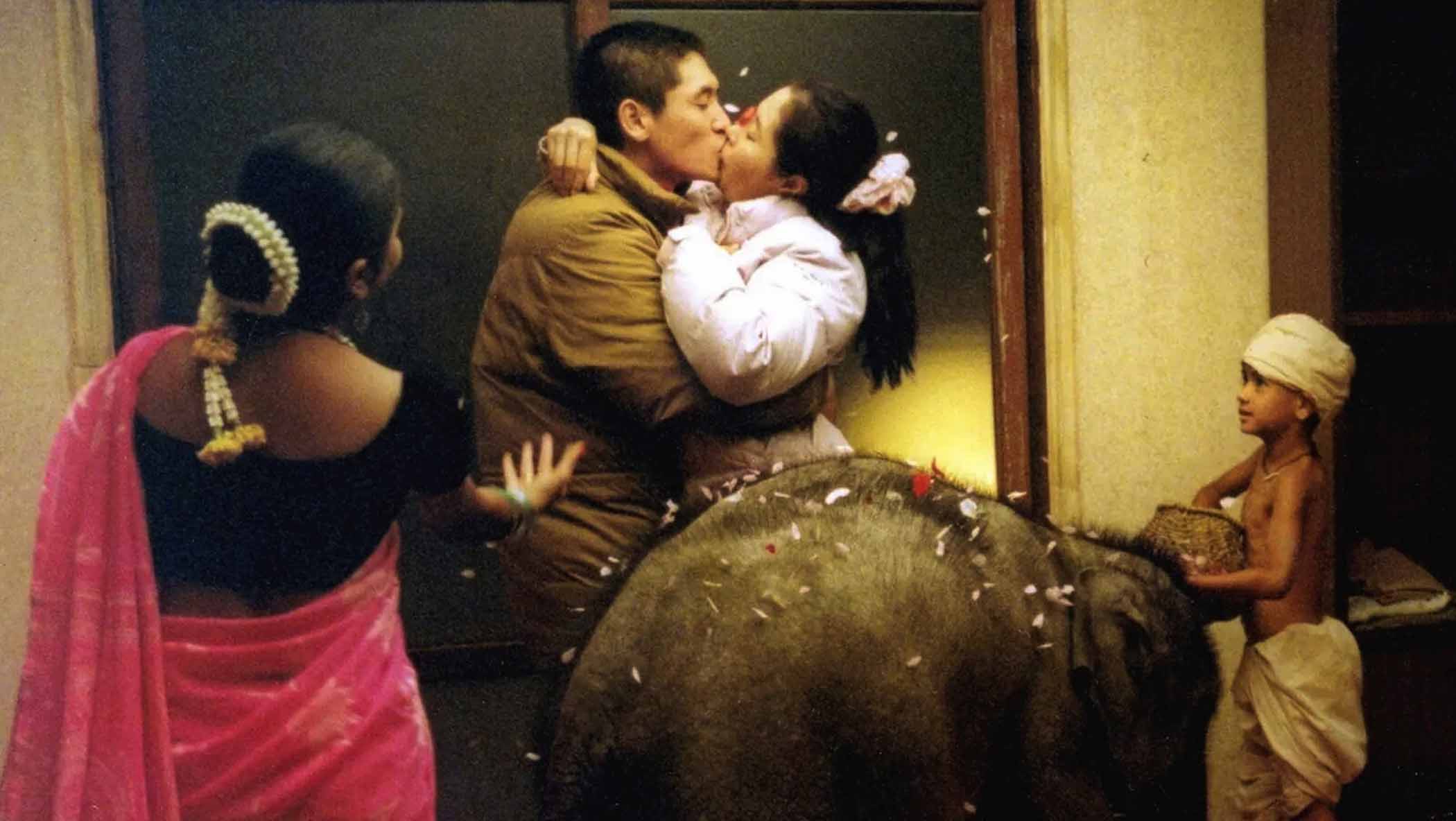

Candy was Lee’s second film; Green Fish (1997), his first, pulses and rambles with the same ambivalent will and empathic narrative taffy-twisting. Typically, Lee’s stories are never short (Green Fish is the only one squeezing in under two hours), never spare, and rarely structured around decisive dramatic moments — they are, rather, novelistic, burly with crisscrossing motivations, and always oddly tragic. Here, we meet a soldier, Mak-dong (Han Suk-kyu), returning home, just as he tries to rescue a woman from thugs on a train. He gets thrashed for his trouble, but continues to pursue her, even after he finds out she’s the kept woman/girltoy of a Vietnamese gangster. (The beloved South Korean star Song Kang-ho has his first speaking role here, as a henchman.)

In “Green Fish,” every scene takes risks, mostly emotional but sometimes physical. (Courtesy Metrograph)

That’s not all: In the background of Mak-dong’s attempts to find a job, his clumsy efforts at wooing the abused moll, and his eventual acceptance as the gangster’s nutty-nervy lieutenant, is his ambition to restore his ruined family’s roadside restaurant and to reunite the clan, which includes a sister turned to prostitution and an alcoholic cop. It was the first and last time Lee indulged in the over-familiar Asian ardor for the gangster film, but every scene takes risks, mostly emotional but sometimes physical, culminating in a climactic family picnic that quickly devolves into a mortifying, drunken, spite-filled debacle — a disturbing set piece Lee would return to. In the meantime, there are humiliations, beatings, murders, and sex slavery, none of it regarded by any of the characters as particularly tragic; it’s just the way of the modern world. In the center of it all is a willow tree that, for Mak-dong, means everything.

Oasis (2002) was Lee’s global breakout film, yanking awards at film festivals, including five from Venice alone. Part of the K-wave’s brand at that point was trafficking in emotionally toxic pulp, but Lee’s film was a rangier and riskier experience than world audiences were used to. Employing a loose, grainy vision of cramped urban coexistence, the movie begins with Jong-du (Sol Kyung-gu), a rarely observed breed of movie varmint: Adenoidal, impulsive, fresh from a prison stint for drunk-driving manslaughter, Jong-du seems at first to be either mentally deficient or sociopathic. In one of several of the film’s cataclysmically uncomfortable restaurant skirmishes, the hapless parolee tries to convince the waitstaff to let him leave his shoes in lieu of a giant meal tab. Soon it’s apparent that Jong-du is one of those square pegs you don’t often see in movies, a person who always stands too close to strangers, never says the right thing, and can’t help defiling social norms; he even goes to visit the family of the old man he killed, expecting to amiably apologize.

He’s cast out, of course — even his own family avoids him — but not before he sets his sights on his victim’s daughter, Gong-Ju (Moon So-ri), a girl with severe cerebral palsy. Lee’s introduction to her is a swoony indication of his movie’s contrapuntal nature: The perfectly real white dove we see fluttering around Gong-ju’s apartment turns out to be, in a blithe cut, the sunlight she’s shakily reflecting from a handheld mirror. Throughout, Lee’s handheld realism gives way to moments of matter-of-fact lyrical sorcery, most often when, as a wickedly unlikely romance blooms between these two, Moon will suddenly relax her character’s harshly twisted deformity, spring out of her wheelchair, and dance. Somehow, the subjective abandonment of Gong-ju’s confining physicality — in effect, allowing us to see the distance between Moon’s lovely vibrant self and her damn-the-torpedoes imitation of handicap — only brings us in closer, refocusing our gaze on the woman rather than the infirmity. You begin to look forward to those moments, as when Jong-du is carrying her on a subway platform and you see her hands relax, abruptly able to hold him back.

Oasis displays astonishing confidence: Jong-du’s first reaction to Gong-ju is to try to rape her, a taboo-lacerating scene that meets its comeuppance later when the couple’s first consensual encounter, itself a tearjerking marvel, is found out and confronted by their outraged (but covertly amoral) families. Lee effortlessly creates a dense social context for his star-crossed lovers, from the bookending sojourns to the unforgiving police station to one of cinema’s most discomfiting and confrontational extended-family dinner scenes, but the film remains unnervingly intimate, because Lee is simply more attentive to his characters’ emotional tumult than to the audience’s, come hell or high water.

The next ordeal, Secret Sunshine (2007), focuses on Shin-ae (Jeon Do-yeon), a willowy, not-too-pretty young mother relocating to the obscure burg her dead husband came from (literally, a village called Secret Sunshine), for obscure reasons. Reserved and cagey, Shin-ae herself remains a mystery, as she resists the gang-press of gossipy neighbors and over-friendly men (including congenial mechanic Song Kang-ho), plays with her headstrong grade-school son, and sets up a storefront piano school. Her unsettled life, and the mellow rhythms of the film, get scorched when her boy is kidnapped and then found dead, launching Shin-ae into a cascade of walking death, beatific Christian born-again-ness, leveling disillusionment (she decides to “forgive” the imprisoned killer in person, never a good idea), and self-destruction. Filthy with unforgiving Holy Shit scenes you want to look away from, it’s one of the most eccentric and uneasy explorations of grief in international cinema, suggesting it as an almost biological tribulation, like a parasite slowly chewing up its host from the inside. The red-eyed Jeon, landing Best Actress at Cannes in 2007, goes to hell and back, and you wonder, almost self-defensively, how much an actor is changed as a person by the experience of being run through the shredder of Lee’s filmmaking process.

Poetry (2010) is at first blush unusually gentle for Lee. Veteran Korean star Yun Jung-hee, something like the Korean Ellen Burstyn, and long retired when Lee persuaded her to make the film, stars as 66-year-old Mija, a rather feather-headed widow-grandmother stuck in a small town nurturing her ne’er-do-well teenage grandson (Lee David) and caring for a wealthy stroke victim to earn cash. Mija is a distinctive piece of work — like so many of Lee’s characters, she’s not terribly sophisticated, but you can’t quite pin her down, and you’ve never seen anyone in a movie quite like her. Dreamy but practical, easily hypnotized by flowers, in love with floppy hats and floral print outfits, cultured but actually not very educated, Mija is a caterpillar who forgot to metamorphose into a butterfly, and implicit in her every action is a quiet resistance to the disappointment of her life. So she decides to take a poetry-writing class, because “I like flowers and say odd things,” considering poetry not as a cultural craft (she never reads any), but as a way to rescue her life from mundanity.

Mija’s slowly onsetting Alzheimer’s deeply muddies her waters, but not quite as badly as a lunch to which she is brought by the fathers of her grandson’s friends — who inform her that the drowned schoolgirl we saw floating down the river in the film’s very first scene committed suicide because the sons were all gang-raping her for months. Now the parents have banded together to cover it up, lest their children’s futures be ruined, a situation that requires a mountainous infusion of cash to pay off the victim’s mother. Cut to Mija, who only wants to sit on a park bench haloed by songbirds and poetic auras. Of course that is only the beginning of Mija’s journey, which in some ways echoes the bystander-to-murder soul-poison in Raymond Carver’s short story “So Much Water, So Close to Home,” and which plays out the typically Lee-esque smash-up between dementia, guilt, culpability, criminal self-interest, and sacrifice. The movie has the breadth and moral weight of a great contemporary novel, and not one that’s been condensed for convenience and concision, though the final passage takes literal flight in ways only cinema can manage.

The lead character in “Oasis,” Jong-du, is a rarely observed breed of movie varmint. (Courtesy Metrograph)

For his most recent film, Burning (2018), Lee adapted an actual piece of modern short fiction, “Barn Burning,” by Haruki Murakami. The story haunts most for what it doesn’t contain: Murakami’s narrator recounts meeting an old girlfriend and her smugly wealthy new mate, who after getting high admits that he occasionally, whimsically, burns down derelict barns for fun. Why he does this, or why it matters to the narrator, is left vague; time passes, the girl vanishes, and the narrator spends years watching for burned barns without ever knowing why.

Characteristically, Lee doubles down on the story’s ellipses, giving its lived-in context four dimensions but never answering the hanging questions. It might be Lee’s tetchiest film yet, a movie of spooky unknown unknowns. Jong-su (Yoo Ah-in), an unassuming delivery boy and wannabe writer in Seoul, is wooed off the street by Hae-mi (Jeon Jong-seo), an erstwhile childhood friend working as a scantily-clad sidewalk hawker. Nothing is simple, but they do hook up, occasioning the first of Lee’s patented metaphoric asides: Hae-mi’s tiny apartment gets only a fleeting sliver of reflected sunlight each day, and during sex, Jong-su sees it glinting on the closet wall, shining and glowing and then disappearing. Nothing stays certain for long.

The absences proliferate: Hae-mi vanishes to Africa and the cat that Jong-su is enlisted to care for never appears, and might not exist, Schrödinger-ishly. When Hae-mi returns, it’s with a new boyfriend, Ben (Steven Yeun), a slick, nouveau riche “Gatsby,” complete with TV-actor profile, a Porsche, and no visible means of support. The three fall into a social routine that Jong-su is either too passive or too polite to resist. He finds himself at parties populated by Ben’s patronizing friends, to whom the naive Hae-mi is little more than the low-class entertainment.

Eventually, a stoned Ben admits to Jong-su that he routinely enjoys burning down greenhouses. Jong-su is as mystified as we are, and that’s when things become entirely unknowable. Jong-su begins worrying about the many greenhouses in the region around his farm and checks them as he jogs; at the same time, Hae-mi stops responding to his messages, and seems to have disappeared again.

Suitably, the film is rather misterioso, boiling slowly and oddly for much of its two-and-a-half-hour length, and then suddenly rising to a crescendo of irrational violence. Lee is as devoted to uncertainty nearly as much as he is to psychodramatic crisis — each of his films, but Burning most of all, is built out of fraught subjectivities and missing puzzle pieces. His entire oeuvre is, ultimately, a distended exploration of how much we’ll never know about those around us, a gimlet-eyed position inflicted with moral force.

Lee’s movies are nothing if not launches of storytelling commitment, wise about mysterious human quandaries, fearless about exploring their fallout. In his world, you go big or go home.

THE FILMS OF LEE CHANG-DONG begins 4/28 at American Cinemateque, presented by Film Movement: www.filmmovement.com.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.